These drawings of a cow by Van Doesberg were made in 1917 and were a classic illustration of the process of abstraction. Cow number 4 (above) being less abstracted than cow number 6 (below). Basically in order to abstract you need something to abstract from, so that in all true abstract work there is a relationship between the 'real' world and the abstracted image.

It was Mondrian who set the standard for this approach, drawing upon the example set by Cubist artists.

Malevitch founded Suprematism which was an art movement with a title that celebrated a non figurative art based upon "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than on visual depiction of objects.

Constructivism as a term was invented by the sculptors Pevsner and Gabo who developed an industrial, angular style of work, more aligned to the aesthetics of engineering drawing, while its geometric abstraction owed something to the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich. Again something that looks similar to something else is at its core quite different. Malevich came up with the title Constructivist as term of derision. He was trying to criticise those who were celebrating engineering in their work, rather than providing pure form to meditate upon. He saw his own work as being very spiritual, for Malevich the constructivists were too interested in linking art to social improvement, he disagreed with their didactic stance, seeing art as being beyond such socialist ideals. Rodchenko was a constructivist, his compass and ruler constructions perhaps being some of the earliest drawings that simply celebrate geometric construction as an aesthetic in its own right.

Constructivism continued as a movement, with many off-shoots such as De Stijl or 'concrete art', the goal of which was "to develop objects for mental use" and to produce "the purest expression of harmonious measure and law". All these movements shared an underlying principle that art and a pure universal idea of form are inextricably linked and celebrate the power of geometry as a formal device. These ideas would quickly spread throughout Europe, artists such as Ben Nicholson introducing Gabo and Mondrian to England before they moved on to the States. Gabo had also written the defining text on constructivism and contributed to the Circle magazine that Nicholson edited.

The difference with more contemporary artists such as Kenneth Martin was that artists were becoming more interested in the underlying mathematical processes that lay behind the power of geometry to appear so authentic or 'right' and less in the spiritual aspects that had initially drawn artists such as Mondrian and Kandinsky to Theosophy and the works of Madame Blavatsky, the younger artists work often being made to demonstrate the implications of certain formal decisions based on numerical principles. As you can see from these drawings by Kenneth Martin below, he had a deep understanding of numerical processes. Martin (together with his wife Mary) used to teach occasionally at Newport when I was a student. He would sit down and talk through very complex visual geometries and expect all us students to be able to follow him. I really felt the art and science divide, most of us had gone into the arts because we were rubbish at maths and Martin was one of those few people at art college that questioned our too easy dismissal of scientific principles, empirical evidence and mathematical rigour.

However in the late 60s the Tate Gallery held an exhibition called, 'The Art of the Real'. This exhibition introduced Minimalism to the UK. Again the works on display looked very similar to previous 'abstract' art, but the theoretical game had changed. Gone were all references to the spiritual or the beauty of geometric form. This art was about 'reality', the object was now what paintings and drawings aspired to. Typical of conversations at the time was this one of Frank Stella's who in 1967, turned down Kenneth Tyler's invitation to make prints at the Gemini G.E.L. workshop in Los Angeles, stating that "if he ever made a drawing he used a Magic Marker pen". He did go on to make those prints but his initial response highlights the everyday reality that Minimalist artists wanted to bring to their work. Sol Lewitt is perhaps the most famous of those artists. The drawing below simply demonstrating how many different ways horizontal and vertical lines can be combined to create different tonal values. Nothing more and nothing less. Of course Lewitt went on to make wall drawings, eliminating both the paper surface and the artist's hand, becoming more an 'architect' of drawings, than the earlier more romantic conception of the artist as spiritual or emotional sensitive. See

Rosalind Krauss saw the grid as the ultimate weapon used by modern artists to establish a clear difference between themselves and their more narratively driven forefathers.

The physicality of 'objectness' attracted sculptors back into the drawing field, artists such as Richard Serra looking to make drawings that were as weighty as sculpture, their surfaces being an expression of the physicality of the chosen drawing medium, the support being as important as the materials of application. These drawings became a record of the artist's involvement with materials as well as 'objects' in their own right.

The sculptor Robert Morris was one of the first artists at this time to integrate performance and physical endurance into the field of drawing and abstraction. His Blind Time drawings opening the door to a whole new range of approaches to drawing as a non figurative practice.

What I find fascinating about these different approaches to abstraction is that what at first was a response to a type of objective drawing that was looking for an underlying universal set of forms that could be said to underpin reality, became eventually drawing as a reality in itself. Minimalist artists were well known for stating, "what you see is what you get". This theoretically is the opposite stance to that taken earlier by artists such as Malevitch and Mondrian. Compare the Minimalist stance to this quote taken directly from the Theosophy website, "Abstraction was a formless voice that dissolved the boundaries of the concrete object to allow the flow of cosmic light to spill forth onto an awaiting canvas, the site where the inner and outer realms of spirituality began a new creative evolution".

As a young artist peering at grey images in well thumbed art magazines in the 1960s, images of Malevitch paintings appeared to be very similar to Ad Reinhart's Ultimate painting series, or the British painter Bob Law's numbered paintings. All of these artists were grappling with presenting a way of conceptually understanding the world through making visual statements. The early 20th century however was a time of conflict between the new coming world of scientific technological advancement and a heavily threatened old world of religious beliefs and by the late twentieth century that advancement (in the West) had become a reality, those who still believed in spirituality were seen as dinosaurs. What the 21st century will bring is another matter, it may be that art itself will need redefining, or more likely that the new zeitgeist of global connectedness and ecological awareness will generate new readings and new philosophical positions from which to yet again 'see' a basic 'simple' black square.

This is Van Doesberg's process of abstraction set out in more detail.

Mondrian Self Portrait

Matisse

A lot of artists were interested in the same formal problems, compare the Matisse Portrait above with Mondrian's self-portraits.

The process of abstraction is interesting because it is all about what to leave out and what to put in place. Most early abstractions reduced things to line and most of these lines were made straight rather than curved. There is sense of looking for an underlying geometry.

From the Pier and Ocean series by Mondrian

These early Mondians show how the process was at first a gradual one of stripping down complexities that were first of all drawn from observation, however late Mondians are slightly different.

From: Broadway Boogie Woogie

These later Mondrian drawings (above) are not based on direct observation and are more to do with an investigation of possibilities of rhythm and composition, however they are still related to 'reality' both in reference to the music of the time and the fact that New York city where they were made, is based on a grid system.

Picasso produced a classic set of bull drawings that illustrate the process of abstraction.

Picasso

However it is perhaps in the cartoons of the 1930s and 40s that abstraction and image distortion blossomed into something that was appreciated within popular culture.

Picasso and Disney

Roy Lichtenstein made a series of prints that commented on the process of abstraction from an ironic Post Modern stance. What his work points to is that at some point the link between the referent and the index is at some point broken, abstraction itself becoming what is referred to rather than any outside art subject matter. His last two prints being more 'constructivist', than abstractions i.e. they are constructions in their own right rather than reflections on the underlying geometry in nature.

Roy Lichtenstein

This brings me to reflect on a very similar but fundamentally different background to abstract imagery. This is the non-figurative tradition. Perhaps we shouldn't ever call this work 'abstract' because nothing is actually abstracted. Non-figurative elements are used as forms in their own right. In this Suprematist drawing below the reference is directly to geometry and the power of engineering drawing.

Suprematist drawing

Malevitch founded Suprematism which was an art movement with a title that celebrated a non figurative art based upon "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than on visual depiction of objects.

Malevitch

Constructivism

Constructivism as a term was invented by the sculptors Pevsner and Gabo who developed an industrial, angular style of work, more aligned to the aesthetics of engineering drawing, while its geometric abstraction owed something to the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich. Again something that looks similar to something else is at its core quite different. Malevich came up with the title Constructivist as term of derision. He was trying to criticise those who were celebrating engineering in their work, rather than providing pure form to meditate upon. He saw his own work as being very spiritual, for Malevich the constructivists were too interested in linking art to social improvement, he disagreed with their didactic stance, seeing art as being beyond such socialist ideals. Rodchenko was a constructivist, his compass and ruler constructions perhaps being some of the earliest drawings that simply celebrate geometric construction as an aesthetic in its own right.

Rodchenko compass and ruler drawings

The difference with more contemporary artists such as Kenneth Martin was that artists were becoming more interested in the underlying mathematical processes that lay behind the power of geometry to appear so authentic or 'right' and less in the spiritual aspects that had initially drawn artists such as Mondrian and Kandinsky to Theosophy and the works of Madame Blavatsky, the younger artists work often being made to demonstrate the implications of certain formal decisions based on numerical principles. As you can see from these drawings by Kenneth Martin below, he had a deep understanding of numerical processes. Martin (together with his wife Mary) used to teach occasionally at Newport when I was a student. He would sit down and talk through very complex visual geometries and expect all us students to be able to follow him. I really felt the art and science divide, most of us had gone into the arts because we were rubbish at maths and Martin was one of those few people at art college that questioned our too easy dismissal of scientific principles, empirical evidence and mathematical rigour.

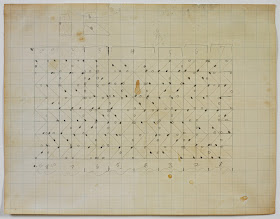

Kenneth Martin Constructivist drawings from the 1960s

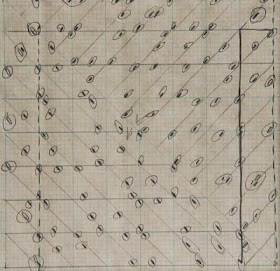

Martin's drawings were nearly always done on graph paper, the pre-existing relationships set up within the graph paper grids allowing him to concentrate on sequential idea development, he accepted that chosen divisions would always be interrelated because of the predetermined underlying geometry of the graph paper grid. During the 1960s, underlying processes became more and more important, as you can see with these Larry Poons drawings below.

Larry Poons drawings

Sol Lewitt

Rosalind Krauss saw the grid as the ultimate weapon used by modern artists to establish a clear difference between themselves and their more narratively driven forefathers.

The physicality of 'objectness' attracted sculptors back into the drawing field, artists such as Richard Serra looking to make drawings that were as weighty as sculpture, their surfaces being an expression of the physicality of the chosen drawing medium, the support being as important as the materials of application. These drawings became a record of the artist's involvement with materials as well as 'objects' in their own right.

Richard Serra and physicality

What I find fascinating about these different approaches to abstraction is that what at first was a response to a type of objective drawing that was looking for an underlying universal set of forms that could be said to underpin reality, became eventually drawing as a reality in itself. Minimalist artists were well known for stating, "what you see is what you get". This theoretically is the opposite stance to that taken earlier by artists such as Malevitch and Mondrian. Compare the Minimalist stance to this quote taken directly from the Theosophy website, "Abstraction was a formless voice that dissolved the boundaries of the concrete object to allow the flow of cosmic light to spill forth onto an awaiting canvas, the site where the inner and outer realms of spirituality began a new creative evolution".

As a young artist peering at grey images in well thumbed art magazines in the 1960s, images of Malevitch paintings appeared to be very similar to Ad Reinhart's Ultimate painting series, or the British painter Bob Law's numbered paintings. All of these artists were grappling with presenting a way of conceptually understanding the world through making visual statements. The early 20th century however was a time of conflict between the new coming world of scientific technological advancement and a heavily threatened old world of religious beliefs and by the late twentieth century that advancement (in the West) had become a reality, those who still believed in spirituality were seen as dinosaurs. What the 21st century will bring is another matter, it may be that art itself will need redefining, or more likely that the new zeitgeist of global connectedness and ecological awareness will generate new readings and new philosophical positions from which to yet again 'see' a basic 'simple' black square.

Malevitch 1915 Black Square

Ad Reinhardt Ultimate Painting No. 19 1953

Bob Law No. 62 (Black/Blue/Violet/Blue) 1967

In spiritual circles, the square represents the physical world, it points to the four compass directions: north, east, south and west. So do we finally come back to Theosophy and the rise of new wave spirituality in order to find a context for contemporary non figurative drawing, or is every stance covered by the blanket term Post Modernism? In several non-European cultures, the square represents male qualities, but what they are is hard to ascertain. It could be the propensity of some men to become computer nerds. Dutch artist Helmut Smits decided to burn a 3-foot by 3-foot square into grass. When it's viewed from 1 kilometer above the ground (3,280 feet) as is a Google map view, it looks just like a dead pixel on a computer monitor.

Relief Structures was an exhibition from 1966 that had a small but influential catalogue. The Artist Andrew Tilberis was still teaching at Leeds when I started work on the Foundation course, he used to make his relief structures inside a specially constructed studio area, sheathed in clear plastic to prevent dust settling on his beautiful flat sanded paint surfaces.

Charles Biederman was as a theorist and artist very influential during the 1960s.

Peter Halley is an artist and writer who had a lot of influence on how abstract art was theorised during the 1980s and 90s. See 'The crisis in geometry' essay in his list of writings.

Fer, B. (2000) On Abstract Art London: Yale University Press

Helmut Smits

ReferencesRelief Structures was an exhibition from 1966 that had a small but influential catalogue. The Artist Andrew Tilberis was still teaching at Leeds when I started work on the Foundation course, he used to make his relief structures inside a specially constructed studio area, sheathed in clear plastic to prevent dust settling on his beautiful flat sanded paint surfaces.

Charles Biederman was as a theorist and artist very influential during the 1960s.

Peter Halley is an artist and writer who had a lot of influence on how abstract art was theorised during the 1980s and 90s. See 'The crisis in geometry' essay in his list of writings.

Fer, B. (2000) On Abstract Art London: Yale University Press

Newman, T. (1976) Naum Gabo: The Constructive Process London: Tate

Krauss, R. (1979). Grids. October, 9, 51-64.

See also:

Non Western Aesthetics A reminder that abstraction can be part of other culture's traditions