My own problem with trying to equate art with science has been how to articulate what ‘knowledge’ is for an artist. For scientists knowledge has to be measurable, any form of truth has to have some form of correspondence in ‘nature’ or ‘reality’. In the social sciences it feels as if everything is located in what I would call ‘propositional’ truths and over the last 40 years of teaching I have seen an influx of social science theory come into the art educational field to support a growing theoretical umbrella that has been constructed around art and its processes. But what sort of ‘knowing’ am I involved in as an artist? I don't think of myself as having to prove anything. I make art out of some sort of personal necessity that has as much to do with hands that need to be busy as a mind that needs to think about what is going on.

I’m also very aware that many of my peers are now involved with PhD study and that the college I work for is now entering a new phase, one that will see far more emphasis on research. From what I have seen, practice based research in the PhD area seems to still hold scientific or propositional knowledge as paradigms against which art practice should be measured. The idea that art practice should be grounded in theory is central to most BA Fine Art curricula and there is an almost tacit agreement that this is vital to a student’s holistic awareness of their developing art practice.

Making or drawing for me opens out an understanding as it is done. It’s not an illustration of a concept about the world, it is a type of knowledge that arrives. However I would argue that this is in parallel with the type of knowledge that arrives when I am in and experience the world itself. I’m often amazed at what arrives out of my mouth when I speak, as Yates said when asked about his poetry, ‘I made it out of a mouthful of air’. Images arrive out of doing something, and then afterwards you begin to think about what they might be about. But how can this be written about?

Heidegger put it this way, ‘…it becomes manifest only through the work, because it lies originally in the work.’ Tom McGuirk's paper ‘Heidegger’s Rift: The Epistemological Significance of Drawing’ available to download at: https://www.materialthinking.org/sites/default/files/papers/TomMcGuirk.pdf

provides an interesting starting point in terms of how you might begin to think about these issues.

Tom McGuirk's paper focuses on Martin Heidegger’s discussion in ‘The Origin of

the Work of Art’ of an observation of Albrecht Dürer’s: “… art lies hidden within

nature; he who can wrest it from her, has it”.

Without trying to go over what McGuirk very adequately covers in the paper, my own observation on this, is that as we are an inseparable part of nature, wrestling something from nature suggesting that first of all you have to get out of nature and escape it, before you can then go back and pull more things out of it. Not I suspect a good thing to be doing.

In 'The Origin of the Work of Art’ Heidegger analyses the meaning of the act of drawing. He sees it as a way to 'tear out' some form of understanding from the world, but also in the making of the drawing, an artist is a form-giver, and it is only, states, Heidegger in this that the human being can learn the greatness of Being. Heidegger also opposes the ‘truth as correspondence’

model of Western epistemology, truth in Greek philosophy he argues being a revelation

of what was not known but now is.

I see this as an argument for the way a drawing can be a becoming, something that arrises out of its making, out of a confluence of materials and their handling, a process rather than an understanding.

Somatic drawing

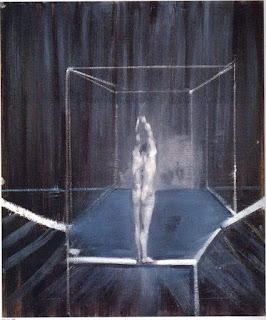

The images of mine I have used to illustrate this post are again on that art / science cusp. I have had to undertake a lot of research into what have been called the 'other senses', those that tell us that we are hungry, off balance, in pain or itchy. The body has its own representational system of corporeal awareness and I have been trying to look into various ways to represent that. The seeming impossibility of using visual representations to make us aware of invisible inner body representations being what interests me.

See also: