Diagrams are powerful things. They have a certain conviction about them that not only helps an idea become clearer, but makes it believable. I'm convinced by Descartes' 'Vortices' below as an image because I've also seen diagrams of how magnets work. Descartes' model of the universe was drawn up in 1644 and was based on his idea that there were invisible whirlpool like forces that moved the planets. These forces, he argued, were composed of some sort of ethereal liquid like matter. His diagram looked at 350 years after it was first drawn, reminded me of those wonderful images made by bubbles as they cling together.

Vortices: René Descartes

Bubbles have often been used to think about hypercubes, which is another idea that is very difficult to think about without a diagram.

Bubble visualisation of a hypercube

From one to two to three to four dimensions

The mathematical reality of the hypercube

An alternative view

A hypercube is though at least theoretically justified and as an idea it rests firmly in the realm of a reasonable possibility. But what about those diagrams of things that are the products of a fevered imagination? I find these just as interesting, perhaps even more so, because what they are doing is making the invisible visible.

Grant Carlin

These diagrams above come from the artist Grant Carlin's website, he is building an imaginary universe, that has its own laws. There are people who have powerful imaginations and a diagram will always help those imaginations actualise themselves.

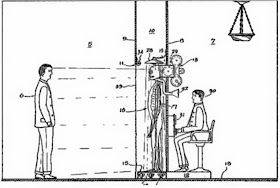

Helene Adelaide Shelby: Apparatus for obtaining criminal confessions

Helene Adelaide Shelby's diagram is less fantastic than Grant Carlin's but in many ways stranger. The idea was to have criminals interrogated by a skeleton, it would have had glowing red eyes and a spectral voice, its operator hidden behind a wall. I was trying to research 'visualising the invisible' and came across her idea by chance. It reminded me of all those thousands of diagrams in patent offices all over the world, many of them never realised, like some sort of psychic energy banks, all waiting for that moment when they will be released upon the world in their full manic glory.

I have been back making diagrams myself, trying to visualise how a particular topographic space could be envisioned, a way of thinking about the body and the spaces it occupies at the same time. It is an interesting process, how do you rethink the way the continuous surface of the body, (think of how the skin gradually flows into the mouth or into your anus or down into a nose or ear), can be understood? Could it be like a Klein bottle? If so how does it relate to more extended spaces?

From a sequence of diagrams illustrating how interoception can morph into exteroception

These diagrams have their roots in René Descartes' Vortices, diagrams that show how to use vectors to visualise changes in a fluid, as well as Faraday's lines of force, but perhaps their real ancestor is Uccello's perspective study of a mazzocchio. Artists and scientists are always trying to re-visualise how to think about bodies in space.

But I'm also thinking of cages and traps, which is why I think Shelby's diagram interested me. However, could a cage become a hypercube?

Cage or trap?

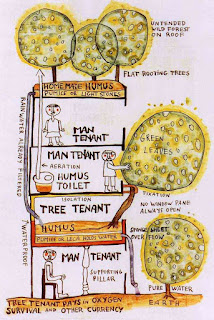

The artist Hundertwasser used diagrams to explain both his world view and how particular projects might work to support that view.

Hundertwasser: The five skins

Hundertwasser's idea of the five skins was another reference I was aware of as I developed my diagrams. The human body and the earth are brought together as if linked by layers, which I was thinking of as topologies. Hundertwasser's diagrams are also womb like, we emerge gradually to embrace the earth and the universe.

I'm very interested in that time around the end of the 19th century, because it was when so many things were about to change and it was as if new ways of thinking were being literally plucked out of the air, from the post-impressionist movement in art, where artists like Van Gogh, Cezanne and Seurat were emerging, to new visions in science and attempts to rethink what religion was all about. In the middle of all this were visionaries who's work didn't stand the test of time, but who's work nevertheless when revisited can offer many insights into our current times. Thomas Kuhn produced a theory about the structure of scientific revolutions, this was often set out as a diagram.

As you can see in Kuhn's diagram above progress in science is not a smooth curve of gradually built information, it is more like a series of jerky movements, whereby the models of the world science gives us begin to feel a bit shaky, and as they do new ideas as to why this is so proliferate, and the end of the nineteenth century was just such a time. Science was in need of some new ways of thinking and Einstein would provide some, but before the new world of quantum theory and spacetime could begin to have traction, a lot of other possibilities also emerged and as an artist I'm allowed to revisit them in my search for ways to visualise the invisible. For instance C. W. Leadbeater's treatise 'Man visible and invisible' details how etheric substances are seen by clairvoyants in their auratic visions.

The astral body of the average man: from Man Visible and Invisible

B. W. Betts work on geometrical psychology fits into a similar category and has helped me to develop a conceptual bridge between the latest work in neuropsychology and the use of diagrams of body image schemas to help demonstrate how intellectual concepts are developed out of a deep body awareness. B. W. Betts: Diagrams from 'Geometrical Psychology'

Rudolf Arnheim's diagrams of underlying structural skeletons and how they explain the dynamic forces at work during the act of perception, are in some way connected to Bett's ideas. For instance Arnheim suggests that a circle or disk if perceived within an image's visual field is affected by hidden structural factors. If seen at the centre of these forces there is a point of balance and rest, and as we move away from the centre, there are other points that are suggested by geometry as also being more in balance or 'right'.

Balance schema based on Arnheim

These points of balance are only balanced in our acts of perception, Arnheim's hidden structures of 'forces' are psychological not actual unlike gravitational forces. This is where Mark Johnson steps in and demonstrates that we then use body schemas to build conceptual ideas via metaphor. In the case of balance, one can easily see a link between visual balance and physical balance. As a young healthy person I stand up straight, but if I am ill or get old I am more likely be become unbalanced and fall over or have to lie down. I can begin to associate certain sorts of real life experience with balance. Gradually I find that I see some things as being 'balanced' and others as 'off balance'. Balance being linked to some form of rightness and off balance as some form of wrongness. Here we begin to see the development of the idea of the scales of justice.

The scales of justice

Two disks in balance

Mark Johnson in 'The body in the mind', again using diagrams, explains how we then build metaphorical extensions and interconnections of balance schemata. The scales of justice emerge from what he calls a 'twin-pan balance'.

Types of balance according to Johnson

Johnson then uses these schemata to show how additional senses of balance are used by what he calls 'imaginative schemata'. Finally he explains how these basic schemata lead to concepts such as the balance of logical argument, legal / moral balance and mathematical equality, such as the = sign. It would also seem that there are various ways that schemata can be combined.

A collection

A merge

Ordering or structuring

You can see these various approaches at work when more complex diagrams are being put together, as in the work of Marc Ngui.

Marc Ngui: Diagram from 1000 Plateaus

Marc Ngui has made a diagrammatic version of Deleuze and Guattari's '1,000 Plateaus' and has applied his skills to other complex bodies of knowledge such as quantum mechanics. What I find interesting is that the diagrams I have looked at come from every discipline, from mathematics, to psychology, economics via philosophy to art, all these disciplines find diagrams powerful communication vehicles. I suppose what I'm also doing here is checking out my own decision to begin creating diagrams to clarify my thoughts about topographic spaces and somatic awareness, some of these issues will therefore no doubt find their way into the writing I'm now doing in relation to how I might visualise inner body perception.