First fashioned he a shield, great and sturdy, adorning it cunningly in every part, and round about it set a bright rim, threefold and glittering, and therefrom made fast a silver baldric. Five were the layers of the shield itself; and on it he wrought many curious devices with cunning skill. Therein he wrought the earth, therein the heavens therein the sea, and the unwearied sun, and the moon at the full, and therein all the constellations wherewith heaven is crowned—the Pleiades, and the Hyades and the mighty Orion, and the Bear, that men call also the Wain, that circleth ever in her place, and watcheth Orion, and alone hath no part in the baths of Ocean. Therein fashioned he also two cities of mortal men exceeding fair. In the one there were marriages and feastings, and by the light of the blazing torches they were leading the brides from their bowers through the city, and loud rose the bridal song. And young men were whirling in the dance, and in their midst flutes and lyres sounded continually; and there the women stood each before her door and marvelled. But the folk were gathered in the place of assembly; for there a strife had arisen, and two men were striving about the blood-price of a man slain; the one avowed that he had paid all, declaring his cause to the people, but the other refused to accept aught; and each was fain to win the issue on the word of a daysman. Moreover, the folk were cheering both, shewing favour to this side and to that. And heralds held back the folk, and the elders were sitting upon polished stones in the sacred circle, holding in their hands the staves of the loud-voiced heralds. Therewith then would they spring up and give judgment, each in turn. And in the midst lay two talents of gold, to be given to him whoso among them should utter the most righteous judgment. But around the other city lay in leaguer two hosts of warriors gleaming in armour. And twofold plans found favour with them, either to lay waste the town or to divide in portions twain all the substance that the lovely city contained within. Howbeit the besieged would nowise hearken thereto, but were arming to meet the foe in an ambush. The wall were their dear wives and little children guarding, as they stood thereon, and therewithal the men that were holden of old age; but the rest were faring forth, led of Ares and Pallas Athene, both fashioned in gold, and of gold was the raiment wherewith they were clad. Goodly were they and tall in their harness, as beseemeth gods, clear to view amid the rest, and the folk at their feet were smaller. But when they were come to the place where it seemed good unto them to set their ambush, in a river-bed where was a watering-place for all herds alike, there they sate them down, clothed about with flaming bronze. Thereafter were two scouts set by them apart from the host, waiting till they should have sight of the sheep and sleek cattle. And these came presently, and two herdsmen followed with them playing upon pipes; and of the guile wist they not at all. But the liers-in-wait, when they saw these coming on, rushed forth against them and speedily cut off the herds of cattle and fair flocks of white-fleeced sheep, and slew the herdsmen withal. But the besiegers, as they sat before the places of gathering and heard much tumult among the kine, mounted forthwith behind their high-stepping horses, and set out thitherward, and speedily came upon them. Then set they their battle in array and fought beside the river banks, and were ever smiting one another with bronze-tipped spears. And amid them Strife and Tumult joined in the fray, and deadly Fate, grasping one man alive, fresh-wounded, another without a wound, and another she dragged dead through the mellay by the feet; and the raiment that she had about her shoulders was red with the blood of men. Even as living mortals joined they in the fray and fought; and they were haling away each the bodies of the others' slain. Therein he set also soft fallow-land, rich tilth and wide, that was three times ploughed; and ploughers full many therein were wheeling their yokes and driving them this way and that. And whensoever after turning they came to the headland of the field, then would a man come forth to each and give into his hands a cup of honey-sweet wine; and the ploughmen would turn them in the furrows, eager to reach the headland of the deep tilth. And the field grew black behind and seemed verily as it had been ploughed, for all that it was of gold; herein was the great marvel of the work. Therein he set also a king's demesne-land, wherein labourers were reaping, bearing sharp sickles in their hands. Some handfuls were falling in rows to the ground along the swathe, while others the binders of sheaves were binding with twisted ropes of straw. Three binders stood hard by them, while behind them boys would gather the handfuls, and bearing them in their arms would busily give them to the binders; and among them the king, staff in hand, was standing in silence at the swathe, joying in his heart. And heralds apart beneath an oak were making ready a feast, and were dressing a great ox they had slain for sacrifice; and the women sprinkled the flesh with white barley in abundance, for the workers' mid-day meal. Therein he set also a vineyard heavily laden with clusters, a vineyard fair and wrought of gold; black were the grapes, and the vines were set up throughout on silver poles. And around it he drave a trench of cyanus, and about that a fence of tin; and one single path led thereto, whereby the vintagers went and came, whensoever they gathered the vintage. And maidens and youths in childish glee were bearing the honey-sweet fruit in wicker baskets. And in their midst a boy made pleasant music with a clear-toned lyre, and thereto sang sweetly the Linos-song with his delicate voice; and his fellows beating the earth in unison therewith followed on with bounding feet mid dance and shoutings. And therein he wrought a herd of straight-horned kine: the kine were fashioned of gold and tin, and with lowing hasted they forth from byre to pasture beside the sounding river, beside the waving reed. And golden were the herdsmen that walked beside the kine, four in number, and nine dogs swift of foot followed after them. But two dread lions amid the foremost kine were holding a loud-lowing bull, and he, bellowing mightily, was haled of them, while after him pursued the dogs and young men. The lions twain had rent the hide of the great bull, and were devouring the inward parts and the black blood, while the herdsmen vainly sought to fright them, tarring on the swift hounds. Howbeit these shrank from fastening on the lions, but stood hard by and barked and sprang aside. Therein also the famed god of the two strong arms wrought a pasture in a fair dell, a great pasture of white-fleeced sheep, and folds, and roofed huts, and pens. Therein furthermore the famed god of the two strong arms cunningly wrought a dancing-floor like unto that which in wide Cnosus Daedalus fashioned of old for fair-tressed Ariadne. There were youths dancing and maidens of the price of many cattle, holding their hands upon the wrists one of the other. Of these the maidens were clad in fine linen, while the youths wore well-woven tunics faintly glistening with oil; and the maidens had fair chaplets, and the youths had daggers of gold hanging from silver baldrics. Now would they run round with cunning feet exceeding lightly, as when a potter sitteth by his wheel that is fitted between his hands and maketh trial of it whether it will run; and now again would they run in rows toward each other. And a great company stood around the lovely dance, taking joy therein; and two tumblers whirled up and down through the midst of them as leaders in the dance. Therein he set also the great might of the river Oceanus, around the uttermost rim of the strongly-wrought shield.

The Iliad Book 18, lines 478–608

Ekphrasis allows Homer two layers of communication, the first and most important via the scenes as they are laid out around the shield, which are set out rather like the script for a graphic novel and secondly those references to the metalwork that has been worked on in the forge of Hephaestus, whereby Homer points to the selective use of tin, gold, silver etc. thus materially reenforcing the narrative.

I have thought myself that the structure of the shield might have been based on one of the forms of memory recall devices that were used before the development of writing as an everyday recording device. Memory palaces or theatres as they have been called, all of which are basically structures you can mentally walk through and as you did you could retrieve parts of a long complicated narrative that you needed to remember. (All described in detail in Frances Yates: The Art of Memory).

One way of visually organising the shield

The text feels quite long, but it was originally meant to be spoken, or recited, a particular 'poetic' voice would have intoned this epic poem and as it is such a long piece, I suspect specialists would have developed all sorts of 'tricks of the trade' to ensure they both remembered what they had to declaim and that they had the necessary voice control to ensure a proper emphasis was placed on the different emotional encounters we are taken into.

The translation of this passage into a visual object is another fascinating aspect of the ekphrasis encounter.

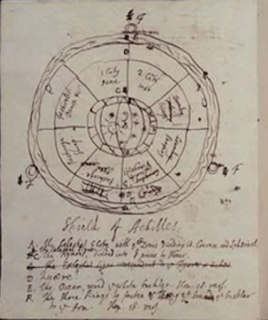

Alexander Pope

Diagram for Achilles’ Shield

The poet Alexander Pope decided to rewrite the Iliad for an 18th century audience and as part of his research he decided to make a diagram of the shield, one not unlike the diagram already used. What is interesting here is that a visual methodology, the diagram, is being used by a wordsmith, the poet in order to come to a better understanding of another poet's words.

The Victorians were fascinated by Classical Greek culture and as they prided themselves that their own culture had great craftsmen too, copies of what was an imaginary object were commissioned.

Rundell, Bridge and Rundell, the London-based royal goldsmiths and jewellers, used 24 drawings and 5 models drawn up and made by John Flaxman over a period of approximately seven years, to create a copy of the shield. He received a first payment of 100 guineas 'for the beautiful design of the shield of Achilles' and a further payment of £200 for the designs on 4 January 1817 and a payment of £525 for the models on 20 January 1818. (Approximately £80,000 in today's money) The final model probably made in wax or clay, was then cast in plaster, and the finer details carved into it. Three bronze casts were made, followed by five cast in silver, one of which was bought by George IV in early 1821 and which remains in the Royal Collection. Rundell, Bridge and Rundell: The Shield of Achilles

John Flaxman: War: Design for the shield of Achilles

1832 illustration: Unknown artist

Angelo Monticelli (1778 – 1837)

As well as Flaxman's designs and Rundell, Bridge and Rundell's recreation, several artists were commissioned to make illustrations based on Homer's text. What is fascinating is that eventually the shield settles down into a visual idea, one fashioned by drawing, rather than making, which is interesting, especially that I haven't seen any references to recreations trying to make for example; "a vineyard fair and wrought of gold; black were the grapes, and the vines were set up throughout on silver poles"; a series of visual effects that were made, I presume, in Homer's imagination, by welding and / or embedding different materials together.

So what was made initially "out of a mouthful of air", as the poet Yates would put it, was eventually written down in Greek, translated into English via Latin and French versions and this one particular imaginary object, was then reverse engineered via its visualisation through drawing, to be eventually reconstructed as an actual metal shield.

As to the encounter between mediums, and being able to gage the effectiveness of one or the other in terms of communicative ability, I think the issue is that the idea was first and foremost poetic, and the natural medium for the description was a verbal one. As we read the text, we get a glimpse of what it would have been like to hear it recited, and when we see the reconstruction, we begin to realise no matter how well the words are used as a pattern from which to create an actual artefact, the complexity of Homer's original thinking is over simplified and what we are left with is a shallow version of a God's design, which could never be copied by mere mortals, because it was an idea and never a reality.

See also:

Drawing with words

Drawing as writing

Drawing as translation

Translation: Drawing between languages

,%201947.png)

.jpg)