The Saint-Bélec Slab, a map of a French river territory, dates back to the early Bronze Age (2150-1600 B.C.)

Some of our

earliest drawings are maps. Knowing where we are is vital to our understanding

of place and action. Because maps are so powerful it’s no surprise that the

military are usually involved in their making. A typical contemporary example being the 'Hebrides Range', a weapons testing zone in UK airspace operated by Qinetiq for the Ministry of Defence.

The 'Hebrides Range' weapons testing zone

Our

existing OS maps derive from conventions for drawing topographical details that were

imported by the British military from France during the 18th

century.

A page

(above) from 'The Book of Practical Geometry' by Henry Fombelle, sets out the symbols necessary

for drawing Topography. You can of course develop your own symbolic forms for whatever it is you want to map. You might also consider whether or not the process ends in drawing or in performance. Boris Nieslony and Gerhard Dirmoser brought these two areas together by making a map of performance art and its various emanations.

Boris Nieslony & Gerhard Dirmoser, Performance Art Context

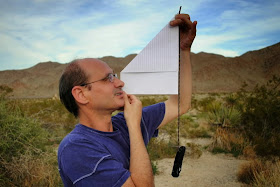

Using a folded sheet of paper to help determine height

Looking along the diagonal of a right angled triangle

To get an idea of height, which is normally put on a map using contour lines, you make a right angled triangle with two 45 degree angles, which is easy to do by folding a sheet of A4 paper as further above. The horizontal length is then equal to the vertical length. You will need a plumb line to judge a vertical, again see the man holding one from his fingers as he also holds the paper taut. Then walk backwards and forwards from the point you wish to measure as a height looking along the diagonal until it is clearly sighted. Mark where you are and then you can measure the distance from your marked feet position to the base of the thing measured, such as the bottom of a wall or base of a tree. You then need to finally subtract your own eye level height from the horizontal distance and that will be the height of the vertical as well, as all you are doing is making a large version of your triangle and the bottom horizontal line will always be the same length as the vertical one. You can also use this method on its side to begin gridding up a flat area of land.

The process may of course become the subject of a video piece, gradually the act of the map construction, overtaking the map itself, life re-emerging from its diagram, in a similar way to the idea Lewis Carroll had in Sylvie and Bruno Concluded.

"What a useful thing a pocket-map is!" I remarked.

"That's another thing we've learned from your Nation," said Mein Herr, "map-making. But we've carried it much further than you. What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?"

"About six inches to the mile."

"Only six inches!" exclaimed Mein Herr. "We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all ! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!"

"Have you used it much?" I enquired.

"It has never been spread out, yet," said Mein Herr: "the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight ! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well." Lewis Carroll from Sylvie and Bruno Concluded.

Dance diagrams are essentially maps of the dancefloor, this time incorporating directions for movement. Think of a standard map with actions added in.

Drawing was a key tool often used as it still is today very technically. That technical precision was what Duchamp called 'dry' drawing. Compare his technical ideas for artworks with the image above and a more contemporary engineering drawing below.

"What a useful thing a pocket-map is!" I remarked.

"That's another thing we've learned from your Nation," said Mein Herr, "map-making. But we've carried it much further than you. What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?"

"About six inches to the mile."

"Only six inches!" exclaimed Mein Herr. "We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all ! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!"

"Have you used it much?" I enquired.

"It has never been spread out, yet," said Mein Herr: "the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight ! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well." Lewis Carroll from Sylvie and Bruno Concluded.

Borges takes on Carroll's idea in his short story, 'On exactitude in Science', whereby he imagines an empire where the science of cartography becomes so exact that only a map on the same scale as the empire itself is good enough for the emperor. Stephen Walter in a related fashion creates landscapes where objects are slowly taken over by their symbolic representations. He is also obsessed by detail.

Artists have had a variety of

approaches to map making, Stephen Walter's of London are very subjective, and full of details, whilst the Fluxus artist Toshi Ichiyanagi’s Music for Electric Metronome from 1960 is a sort of map for a choreographer.

Toshi Ichiyanagi Music for Electric Metronome

In fact maps can be very like musical scores. Yasunao Tone’s Anagram for Strings, 1961 has the

familiar grid of measurement we usually find around the edges of a map. The measurement of time in music perhaps could be seen as similar to distance when walking through a landscape.

Yasunao Tone Anagram for Strings

John Cage obviously saw the connection between musical scores and landscapes, his scores for imaginary landscapes illustrate that exact point.

Gwen

MacGregor and Sandra Rechico’s 'Maps in Doubt' series track

journeys they have had to make in order to develop careers in the now global

art world. They calculated the total distance that each of them

traveled whilst in Kassel in 2007. These distances were drawn

on sheets of paper, one of them making curved and the other straight lines.

Gwen MacGregor and Sandra Rechico

They also produced more 'conventional' linear maps, this time making 3 dimensional constructions that worked across walls and floors.

Gwen MacGregor and Sandra Rechico

The important issue here is that maps reflect a point of view. As has been pointed out earlier maps are often made because of strategic military importance, this view of

Annan (below) from a topographical and military account of the state of the Marches,

1569, was made because the town commanded an important defensive position on the estuary of the

River Annan, and it was therefore important for the military to map its

position. It fuses flat symbolic imagery with attempts at representation in a fascinating way.

Similarly in this plan of

Dover Castle from 1752, the positions of batteries of cannon are detailed as well

as individual big guns. The 'legend" on the left is another typical feature of map design and it can be used by an artist to add textual information into an already complex visual mix of languages.

Drawing was a skill taught to many people of all ranks and professions, once again though it is a drawing done by a serving officer which helps us to understand how information was brought back home pre camera. This image (below) by Lieutenant Archibald Campbell of Fort Royal on Guadeloupe in the West Indies drawn during the 1760s was engraved on his return to England and prints kept in the War Office records.

Precision

measurement of a baseline would be of little use in a trigonmetrical survey

without an instrument capable of measuring the angles between it and distant

points with comparable accuracy. The instrument designed to do this, a

theodolite, is essentially a rotating telescope mounted on a circular

scale.

The 'Great Theoldite' was eventually delivered to the Board of Ordnance

in July of 1787. Three feet in diameter, it weighed 200 pounds and was

transported in its own four-wheeled horse-drawn carriage. The magnificent brass

and wood instrument is seen here in an illustration drawn by Lieutenant Thomas

Vincent Reynolds for a presentation to the Royal Society by William Roy in

1790.

Duchamp drawings for the large glass

A technical drawing printed off using a 'blueprint' process

Duchamp: Network of Stoppages

Network of Stoppages contrasts three representational systems: traditional figuration, chance operations, and the diagram, mapping the world without picturing it. Duchamp pointed to what he called the casting of "Pataphysical doubt" on the viewer. Duchamp introduces the idea of working conceptually, and all maps are conceptual representations, which is why he is so interested in them, as well as other more scientific means of representation, such as technical drawing.

Royal support for the advancement of science was vital during the 17th and 18th century, these three views below of the Royal Observatory in Paris, 1705 demonstrating how important scientific measurement was becoming at the time. Of course as images they are very interesting too and they remind me of the contemporary work of Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin the paper architects.

Alexander Brodsky and Ilya Utkin

Brodsky and Utkin had an exhibition at Tate Modern recently and their large scale etchings use many of the conventions of scientific illustration from the 18th century. By looking backwards at older traditions artists can re-ignite a fresh engagement with the world. In this case Brodsky and Utkin are able to give conviction to a contemporary fantasy by using a language that used to be used for scientific purposes. (See)

The precision and control that early map makers used to embed within their development process is demonstrated in this image below of the 4 stages of development of an OS map.

Ordnance

Survey maps were produced in four stages. From their field notebooks, surveyors

made a rough or 'foul' plan. This first draft was followed by an intermediate

or 'proof' plan, which was carefully checked for accuracy.

A 'fair plan was

then made at the reduced scale of one inch to the mile, sometimes with

colouring. From this fair plan, a copper plate was engraved printing the

finished map.

I'm fascinated myself with the relationship between maps, direct observation and memory, some of my own drawings (below) being an attempt to fuse together these very different ways of seeing.

Marking territory is of course something all animals do and one way to begin thinking about mapping an area is to simply begin by making marks that sign that you are here. The images below are the marks of bears doing the same thing. This takes us back to a much earlier post on traces and marks of passage. This is perhaps where all drawing languages begin, making a sign that 'I was here'. See post on mimesis, and how drawing languages evolve.

Useful links

Is this so different to a bear marking out territory?

On Kawara used to mark out on a map where he went everyday, in a similar way to how he dealt with recording time. These simple ink on photocopy drawings began to have more gravitas the more he did. This sequence was of nearly 4,000 drawings.

On Kawara: New York from 1968 to 79

Ink on photocopy

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment