Nidhal Chamekh

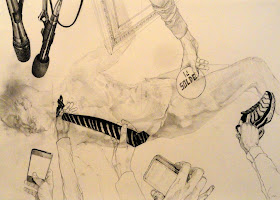

Nidhal Chamekh had two distinctly different bodies of

work on show. The first was perhaps more traditional, and consisted of a series

of approximately A2 size drawings, hung framed in 2 rows. The drawings were

fragmented images, sometimes using biro and at other times more traditional

‘art’ media. They also included Arabic script. He is obviously interested in

science and its ‘objective’ status, the drawing often using engineering cross

sections or biological illustration, off set against more emotive subject

matter. Chamekh grew up in Tunis, and his family were involved in militant

action, so he would have experienced the chaos of war from an early age. It has been said about his work that it works

as,“ a ‘sampler’ of

the chaos of history”. He uses montage techniques to construct his images, but has

a really good sense of design, so that as he builds these images they are still

readable and not too confused. Often hand drawn, rather than actually collaged, but combined with the use of transfer techniques (see) his

imagery relies on a basic recognition of the artist’s rendering skill as a

metaphor for ‘care’ and ‘attention’

Nidhal Chamekh

Like several other

artists at Venice Chamekh also uses models to visualize his ideas

and his second exhibit was an installation of drawings placed next to a model

of a city that had a rolling ball on a track that ran over the buildings below.

This time the drawings were all focused on ideas of time. He is obviously trying

to deal with the significance of the stopped clock. Time arrested suggesting

that moment when we take stock, or a period when we await a dramatic happening,

time seeming to stand still just before a tragic event.

Nidhal Chamekh

It was also good to see the drawings of William

Kentridge again. Another artist who has often responded to political events in

his past work, this time however he was looking back into history and the way

that wars and the victims of war are a long running theme in art history. He was

asked to respond to being part of the Italian pavilion and took the opportunity

to revisit old images of Italian martial history, reminding us of the ever constant violence

that seems to pervade human history. I was particularly interested in the way

he worked from existing imagery and made it his own through his particular use of

expressive charcoal and ink drawings.

This was a very large ink and brush drawing, covering several sheets of paper.

One ink drawing in particular (see above) had been enlarged and then cut out, (I presume laser-cut), it was then hung and mounted against a brick wall. I didn’t think it really added to its effect, but it was interesting technically.

William Kentridge

Finally a reminder that you can always be on the

lookout for new ways of presenting drawings. Terry Adkins had had a series of

drawings/prints displayed using a hinged rack. It looked as if it was designed

for a commercial outlet, and added a ‘consumerist’ message to his images

because of this.

Terry Adkins

I could continue to put up posts on Venice, but

perhaps this is enough for now. I am aware that some of you may well be going

there this coming semester, if you do, try and use the experience to think about

your own work’s ambition and where you perhaps stand in relation to the

possibility of making work that has a political or moral dimension. This is not

to say it has to, but simply one of those experiences that can help you when

positioning your practice. It may also be a useful experience even if you

hate the work on show, this can be a very powerful indicator that you either

need to confront these issues or that your work should be non political

and if this is the case you will be in agreement with some of the most revered thinkers

in aesthetics. Kant’s ‘disinterested interest’ pointing to a position in

aesthetics whereby the artist’s job is not to comment on the world or try to change it but to

observe it and the way it operates.

See also:

2022

Venice Biennale 2022 Part three

Venice Biennale 2022 Part four

2019