Daniel Lebeskin

Re-visiting the post on Daniel Lebeskin's drawings reminded me that I had a draft post on technical drawing that needed adding to. I am always interested in how small differences in appearance can mean a lot when constructing a drawing and this is the same when dealing with technical drawing as it is with more expressive drawing conventions.

Most technical drawing systems were determined by draftsmen who needed to ensure their drawings could be read by the people who worked from them. Therefore one of the key issues was that measurements could be transferred accurately.

In a perspective drawing things get smaller as they recede away from the picture plane, this gives a powerful and convincing depiction of objects moving away from us, but for an engineer this is far too 'emotional' to have any direct use value. A technical drawing focuses on 'the object' of the drawing, whilst a perspective drawing is orientated towards the viewer and highlights the relativity of the viewer/object duality.

One way of thinking about the difference between the types of technical drawing systems is where the initial visual interest lies. Plans, sections and elevations (orthographic drawings) indicate two dimensional thinking, whilst axonometric drawings use the three axes of length, width and height for measurement and all measurements in these directions are made parallel to these axes. They are literally three dimensional.

A plan is also about shaping up an idea, a plan reduces three dimensional complexity and by reducing the amount of information allows you to concentrate on specific aspects of an idea of something.

T.N. Architecture

The drawing above by T.N. Architecture is concerned with an idea of 'narrative cities' stories about a city's formation, function, and ideology. The city is seen from above and events are moving, lines contact one another and each line has a different character expressing a different function or idea. It is a plan, an idea of a possibility and both artists and architects understand how powerful plans are.

Bruce Nauman: Exhibition plan

The drawing above is by the artist Bruce Nauman and is a plan for an exhibition. He is thinking carefully about how to articulate the spaces and where projectors need to go. The plan view allows him to focus on the problem.

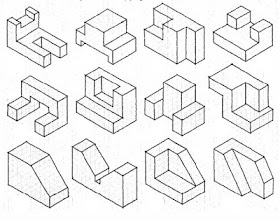

In an isometric projection the focus is on the edges of a shape, and by drawing the sides moving off at 30 degree angles, an equal emphasis on both sides of a space or object is maintained. If you look at the drawings below you can get a very clear idea of their three dimensional shape and both sides of these objects are given equal visual weight.

In the drawing below by Osbert Lancaster we have an 'almost' isometric drawing. There is a touch of perspective added by shifting the drawing slightly off the underlying parallel lines. If you look at the angle made by the back edge of the drawing it would eventually meet at a long away vanishing point the angle coming from the front edge. This compromise is fine for a cartoonist but would be of no use for an engineer. The point here being that as an artist you can merge or blend together different types of visual projection in order to achieve the type of space that works for your idea.

Isometric: Osbert Lancaster

Escher

The image above by Escher uses the spatial ambiguity of an isometric projection to allow him to develop spatial paradoxes. See more thoughts on these issues here.

Oblique: cavalier projection by Chris Ware

In the oblique projection used by Chris Ware the emphasis is placed directly on an entry into the space from the front edge of the image. As you move into the space it is cut into by slices making it harder to read what is in spaces further back in the drawing than it would be if an isometric had been used, but Ware is aware of this and his spaces are made to control and host uncomfortable psychological narratives. Oblique projections are usually drawn using either 45 or 63.5 degree angles. There are two sorts, cavalier and cabinet projections. In the drawing above we can enter the space from the front and the right hand side. In comparison the Osbert Lancaster drawing feels a little less constrained and regimented.

In a Cavalier projection the direction of projection is at 45 degrees to the horizontal and line lengths are as measured.

In a Cabinet projection the direction of projection is at 63.4 degrees to the horizontal and dimensions parallel to the third axis of the object are shortened one half to overcome apparent distortion.

Of course an engineer would prefer a cavalier projection because all measurements are as measured, but cabinet projections were developed for joiners who preferred to work from the look of the drawing rather than working from exact measurements.

Oblique projection

Claes Oldenburg using a plan driven isometric drawing system.

The Oldenburg drawing above shows the shapes of the Micky Mouse head in relationship to the interior spaces made by the building, in particular clearly locating the 'tongue' entrance. The plan view of Micky's head drives the overall concept of the building.

Typical tiled space in a computer game with isometric buildings

In computer and video games isometric projections were used because of the ease with which 2D sprite and tiled graphics can be made to represent a 3D gaming environment. Because parallel projections of objects do not change size as they move around the game field, there is no need for the computer to scale sprites or do the complex calculations necessary to simulate perspective. This allowed older 8 and 16 bit game systems and handheld devices to work with large 3D areas easily.

Paul Noble

Paul Noble often uses cavalier projection to organise his large drawings. He has this to say about why.

'I use the devices of technical drawing. These devices help shine the sharpest light on the things I depict. I am against hierarchies and perspective. I arrange the objects of my drawings on a spatial plane using cavalier projection. The origins of this projection lay in military cartography - fore, mid and background are got rid of and everything depicted is equally close and far. The viewer becomes the architect and the drawing, an architectural plan. He or she is no longer earthbound but hovers like an angel over the described scene, taking in the entire design'. Get full article here.

In comparison it's interesting to look at how architects think about space. A very good book to read is:

As an introduction to these issues watch and listen to David Hockney reflecting on the Chinese scroll painting A day on the grand canal with the Emperor of China.

In the section taken from a Chinese scroll painting above you can see the use of oblique projection, because the artist didn't have to make things smaller in the distance it allows the image to be peopled in both near and far space. By using oblique projection the artist is also able to 'open' the front of the room spaces of the buildings, so the people can inhabit them. Notice the way that the bridge is distorted into the space. Because of the 'awkward' compression, it generates considerable spring-like dynamism into the flat surface. In comparison a bridge in perspective would simply create a deep spatial recession. The curves of the boats in this case echo the curve of the bridge, which is then echoed by the small curves that represent the water.

In comparison it's interesting to look at how architects think about space. A very good book to read is:

EnvisioningArchitecture: An Analysis of Drawing by Iain Fraser and Rod Henmi (1993), the book deals with the technical differences between approaches as well as opening out the debates surrounding philosophical and conceptual reasons for choosing different types of drawing projections. For example in a discussion relating to Suprematist uses of technical drawing, El Lizzitsky stated that "Suprematism has shifted the top of the finite pyramid of perspective into infinity". Like Noble he also pointed out that axonometric constructions are spatially non-hierarchical.

These are old problems, and Chinese artists faced a similar set of issues when working on scroll paintings. They use both isometric and oblique projections in their work.As an introduction to these issues watch and listen to David Hockney reflecting on the Chinese scroll painting A day on the grand canal with the Emperor of China.

In the section taken from a Chinese scroll painting above you can see the use of oblique projection, because the artist didn't have to make things smaller in the distance it allows the image to be peopled in both near and far space. By using oblique projection the artist is also able to 'open' the front of the room spaces of the buildings, so the people can inhabit them. Notice the way that the bridge is distorted into the space. Because of the 'awkward' compression, it generates considerable spring-like dynamism into the flat surface. In comparison a bridge in perspective would simply create a deep spatial recession. The curves of the boats in this case echo the curve of the bridge, which is then echoed by the small curves that represent the water.

Computers and the drawing tools they bring with them have now been around for quite a few years. The Autocad systems that I had to learn during the 1980s have now all been superseded but the basic idea of constructing around an x, y and z axis and linking to co-ordinates remains the same. SketchUp is perhaps the easiest and most useful of the new range of software. The use of SketchUp is now so common within the art community that there are artists' residencies dedicated to it.

SketchUp has very good 'how to' videos that you can use to get a grip on how to use the software, it's a pretty easy learning curve and you can get downloaded trial versions to try out. It seems as if both the architectural profession and science fiction illustrators have capitalised on SketchUp's ability to build complex solids by joining surfaces and pushing and pulling various combinations of volumes in and out from them.

I have seen SketchUp used by a variety of artists, sometimes to visualise ideas for public art installations and at other times to provide gallery walk through models to get an idea of how an exhibition might look. It can of course be used as a tool to make visible any sort of idea that can be carried within technical drawing conventions, and SketchUp does allow you to move from one convention to another.

The artist Avery Singer uses SketchUp to develop ideas for paintings. This is a very old idea and like so many drawing issues goes back to the Renaissance concept of 'disegno', the Italian word for 'fine art drawing'. 'Disegno' implies that drawing is not just about a certain type of draftsmanship, but that it is also a 'design' or plan for something else. It is an intellectual concept, whereby ideas are made visible, therefore it comes before and is the foundation upon which the arts of architecture, sculpture and painting are built.

SketchUp has very good 'how to' videos that you can use to get a grip on how to use the software, it's a pretty easy learning curve and you can get downloaded trial versions to try out. It seems as if both the architectural profession and science fiction illustrators have capitalised on SketchUp's ability to build complex solids by joining surfaces and pushing and pulling various combinations of volumes in and out from them.

I have seen SketchUp used by a variety of artists, sometimes to visualise ideas for public art installations and at other times to provide gallery walk through models to get an idea of how an exhibition might look. It can of course be used as a tool to make visible any sort of idea that can be carried within technical drawing conventions, and SketchUp does allow you to move from one convention to another.

The artist Avery Singer uses SketchUp to develop ideas for paintings. This is a very old idea and like so many drawing issues goes back to the Renaissance concept of 'disegno', the Italian word for 'fine art drawing'. 'Disegno' implies that drawing is not just about a certain type of draftsmanship, but that it is also a 'design' or plan for something else. It is an intellectual concept, whereby ideas are made visible, therefore it comes before and is the foundation upon which the arts of architecture, sculpture and painting are built.

Avery Singer

Avery Singer

Avery Singer has also recognised the power and fascination that drawing systems have held over artists over hundreds of years and her images are direct references to those made during the early development of perspective systems.

Compare her paintings above with the drawings of Erhard Schön and Luca Cambiaso.

Erhard Schön

Erhard Schön

Luca Cambiaso

Luca Cambiaso

As I've pointed out before, if you want to try out some ideas using technical drawing conventions, why not download some graph paper to print off and then put that under some big sheets of tracing paper and freehand draw or use a ruler, whilst keeping your eye on the grid beneath. You will find both perspective and isometric graph papers here.

There is an earlier post dedicated to the technical aspects of drawing in perspective and the artist Jenny West who teaches at LCA has a practice that is focused on perspective. The Venezuelan artist Rafael Araujo uses perspective to explore the dynamics of natural forms and often starts with plans and elevations of spaces within which to develop his complex perspectives. Although perspective is about viewpoint, it can also be very technical and you can use plans and elevations to drive the construction of these drawings, when you do, you are also bringing together into one technical drawing format a rich visual language capable of holding within it very sophisticated concepts.

Rafael Araujo: Perspective of a butterfly flight path

A ruling pen is something many people have forgotten how to use, but they are still worth exploring if you are to take technical drawing seriously. The image above is simply there to show you what they look like, its great advantage is that you can mix your own ink and paints to draw with and quickly adjust the thickness of your lines. The disadvantage is that they are very hard to control. But with practice they can be very useful.

Finally I have mentioned aesthetic protractors before so perhaps it might be useful to see what they look like. In this case we have a traditional technical drawing instrument calibrated in such a way that an artist can make direct links between a chosen angle and an emotional measurement. By using this instrument you can find the angle of naked pain and other nerve patterns. Find out more here.

James Elkins The Poetics of Perspective is a very good read if you are interested in these types of issues.

The way that technical drawings used to be printed is an aesthetic in its own right. You can explore some of the methods here

See also:

Euler spirals

Abstraction and metaphor

Bezier Curves

The way that technical drawings used to be printed is an aesthetic in its own right. You can explore some of the methods here

See also:

Euler spirals

Abstraction and metaphor

Bezier Curves