From insignificance to significance

Same subject different moods (the search for a way of working with figurative images that suits you)

First of all you need to choose a subject to look at. You can pick a photograph or a view, a still life or a person you know, or an imaginative image previously made; anything that you feel comfortable drawing.

You will now set out to draw the same thing twice but with two totally different approaches.

You need to put aside the same amount of time for the two drawings, so if you have an hour, two 30 minute drawings will need to be made. Make the two papers you are going to draw on square and the same size. They can though be different weights and have different surfaces.

For the first drawing, draw everything smoothly, softly and with an underlying idea of safety. Think about how you hold your pencil, pen or brush, it could be a loose hold, or further away from the drawing tip. Work more from the elbow, think circles and Disney. Think light tones, sunlight suffusing everything, this is like a summer's day when you were a child with no worries. Make all your drawing movements smooth, and the same with any transitions from light to dark, or from one form to another. Keep drawing until your set time is up.

Once done, turn this drawing away from you so you cant see it and begin another drawing, this time thinking, harshness, threat, danger and heightened emotional intensity. Think about the way you move your body in relation to this, find your unsteady jerky inner self. Grab your drawing implement as you would a knife or weapon, stab or cut your way towards an image. Think angular shapes, sharp contrasts in tone, too hasty marks that are unfinished, fragmented imagery made by someone anguished.

Repeat this exercise regularly with different subjects and try out other adjective ‘moods’, try 'shyness' or 'lost' for instance as emotional states somewhere in between the two extremes given.

What you might find is that certain 'moods' suit you and that you feel more comfortable working with a particular sensibility. If so, now apply it to a range of subjects and see if there is one particular subject that also seems to sit 'right' for you. In this way you might find both a better way for you to work and a subject matter that works for you.

--------------------------------------------

Abstraction and mood Part one

You will need a ruler and compass as well as your drawing implements.

To draw a series of 3 inch squares on a sheet of paper or on several sketchbook pages. Then using only three elements in each square; one straight line, one emotive/hand-made line and a circle or dot, you are to represent as many different moods as you can. You can vary the size of the circle/dot and the length of the lines, as well as the tonal value of either.

Once you have finished by making as many different mood changes as you possibly can, go back through them and try and identify an exact word or combination of words that sums up each of the moods you have created.

There are meant to be four basic moods; happiness, sadness, fear, and anger as well as combinations of these, so you could have someone with a mood that was happiness tinged with sadness or remorse. Anger can be cold, resentful or righteous as well as full blooded, vengeful or stupefying. Remember, an image can represent what is frightening as well as representing the state of being frightened.

Once you get used to doing this, you can take any image and reduce it to three main elements and then follow a similar process.

Abstraction and mood Part two

You will need a range of drawing materials that allow you to make marks of different qualities.

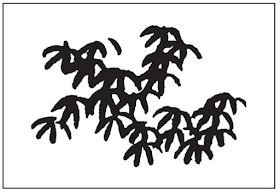

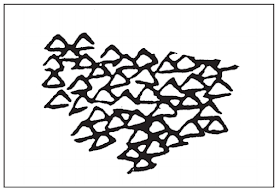

To draw a series of 3 inch squares on a sheet of paper. Then using a range of marks that can be varied in terms of tone, energy, amount and size, you are to represent as many different moods as you can.

Abstraction and mood Part three

To explore the implications of putting together the imagery emerging from part one and part two of this exercise.

Finally see if you can find a verbal equivalent to all the moods explored and then identify those moods expressed that are not verbally translatable.

If this works for you, now try the same thing again adding colour.

Finally try selecting/abstracting a composition from more figurative images and then going through the same process.

-----------------------------------------

Non-dominant hand drawing

Choose your drawing subject, this could be a photograph, something imagined or something seen.

Have ready several sheets of paper, (at least 20) (or a large sketchbook with several empty pages) a drawing board or table top to work on. As well as a variety of drawing materials.

Begin drawing with your non-dominant hand, starting to draw from the top left hand corner of your paper. Keep the paper at arm's length so that you are not tempted to rest your hand on it. Make each drawing using a different material; pencils, pen and ink, biro, felt tips, ink and brush, coloured crayons etc. and do not be tempted to 'correct' any 'errors'.

Once at least 4 images have been made, turn them upside down and repeat the process this time using your drawings as the starting point rather than the original subject. I.e. this time you will end up with at least 16 drawings.

Finally put up an exhibition of your images and select out the ones that intrigue or offer something new or unexpected to a reading of the original subject matter. Think about the process and see if it could be used to develop other subjects or to consider the possibility of taking an existing image on an even longer visual journey.

--------------------------------------------

From insignificance to significance

Make a number of tiny drawings of people on small scraps of found papers or other surfaces, using any materials you can such as biro, pen and ink or felt tips. If you cant make marks on the paper or surface, try whiting out some of it first in paint. The important issue is that the tiny scraps must have had a previous life and that some form of visual information must be still operating as part of its surface quality when you draw your figures. By tiny we are talking 2cm square at the largest, so these scraps will often be torn off larger things and your drawings of people will have to be very simple, as they will be far too small to have any details.

Once made to try and enlarge them up to A4 by using either a photocopier, or a scanner or by simply photographing them and printing off at A4 or any other means that comes to hand. (If you are doing this in a sketchbook, you may simply enlarge images by drawing them much bigger on the facing page)

Now grid up the most interesting A4 image and count the number of squares and make the grid in light pencil, on a much larger surface, such as a wall or very large sheet of paper. (If working in a sketchbook you might grid up a small section and enlarge that.) Now, choosing a drawing material, draw and transfer exactly what you find in every square, onto the large surface. Do this systematically, working from the top left, to top right, slowly working your way down until you reach the bottom right.

Finally carefully remove the lightly drawn pencil grid and make any necessary amendments/corrections.

The process should ensure that your drawing of a figure and whatever was on the scrap of paper beforehand are now of equal visual value. This should help you to now think about possibilities for how a human image can be morphed into new shapes and/or inserted into any image. Above all it will take something that is small and insignificant and it will make an image of it that is large and important enough to be noticed, and this of course reflects a fundamental aspect of any artist's role, the highlighting of things that most people never see or notice.

At this point you may want to work on a new drawing directly with a brush and black ink to further reinforce the form your original tiny figure now takes. If you are someone who enjoys using computer software you might want to use digital approaches to the same idea. This can be a very useful way of re-inventing and simplifying the human body. (See example at the top of this post)

--------------------------------------------

A change of viewpoint

To make a drawing of yourself from the imagined point of view of a fly walking over your body. You may think of yourself clothed or unclothed and may use any device to help you develop imaginative ideas as to how the fly might see you as it travels over your body.

Remember for the fly you are now its landscape experience and that a single one of your hairs might be as big as a tree and a sweat gland more like a marsh.

Your main concern is to see if you can adopt the point of view of a non-human. If you can, can you draw yourself from the point of view of an inanimate object you might encounter?

--------------------------------------------

The most important drawing exercise...ever... Draw something every day

Draw at least one thing every day. Draw anything and everything and keep doing this quickly, taking no more than 10 minutes for any one drawing. This could be the same thing drawn over and over again, each time turning it round to get a different viewpoint, it could be 10 minutes spent at the same time each day drawing whatever scene or situation you find yourself in. It could be drawing your dog, your breakfast, the garden, how water spirals as it runs out of the bath, a tree, a chair, people seen on a train, cars parked, a storm, reflections on water, a house, a cardigan hanging on the back of a chair, passing traffic, your drawing materials, a view from a window, a bottle of beer, literally anything can be drawn. Gradually your control will improve, your selection will become more thoughtful and the range of subjects drawn will help you understand yourself and your proclivities. This is wonderful way of getting used to drawing in sketchbooks, and the more drawings you make, the easier it will be for you will find a sketchbook size and format that suits you.

See also:

An exhibition set out as a series of drawing exercises Follow this link and look at and explore the exhibition themes which were about various approaches to drawing and then choose one approach and make more variations, until you begin to feel you have made something new.