My interest in drawing as 'disegno' is key to my thoughts regarding certain underpinning theoretical aspects of art practice.

During the Renaissance central to the idea of drawing as 'disegno' was the use of drawings as the basic building blocks out of which a finished concept would emerge. On the other hand 'Colorito' was the direct application of colour (paint), to a support, (canvas or a plastered wall). This distinction has a philosophical dimension, one that provides us with a way to look at recent artificial intelligence (AI) applications as a contemporary form of 'disegno'.

An artist who saw themselves as conceptually using drawing as disegno (e.g. Michelangelo) would expect fellow artists to have had a long training in drawing from life and from sources such as classical sculpture, together with an understanding of other forms of drawing such as geometry, compositional structuring, the development of complex figure poses and the use of mathematical proportion. Alongside these practical skills most importantly the artist would have the ability to draw from the imagination; these skills supported an artist's ability to build, construct and paint whatever ideas drawing had allowed the artist to visualise. Disegno both facilitated invention, and the capacity for visualising a concept, such as a building, a painting or a sculpture. It is the imaginative and intellectual core of the process, which elevated 'disegno' and those who practiced it, onto a par with other intellectually demanding areas of human endeavour. This was why artists were able to argue that there was a distinction between a craftsman and an artist and therefore demand more money for their work. This was a division of labour that could be understood by those in power who also no longer had to work with their hands to make a living. I personally think that because this argument was one focused on appealing to those in power who no longer had to get their hands dirty, that the distinction was taken too far and that the more art moved away from its craft base, the more it became estranged from those people who understood ideas via making or using their hands to think with. The more art became an intellectual pursuit, the more it forgot its earlier 'animist' relationship with materials, an understanding centred around the fact that materials had a life of their own. The spirit that used to be sensed in things as they were made was almost lost, but perhaps not forever and recent thinking in particular as laid out in the work of Tim Ingold, has pointed to a re-animating of the ‘western’ tradition of thought. I suppose what I'm circling around is the separation of making real things from the preparing for making them. I'm interested in how drawing allows the imagination to leap forward, and to envisage a possibility but drawing doesn't do the work for you, you will still have to carve that sculpture or get that building built. However entangled up with the material possibilities that confront us, is an ability to visualise possibilities and drawing is entwined within that envisioning process.

I spent some time this afternoon talking to someone who had for years made a living by recycling old materials and re-making it into bags, cases and other useable objects. She had always done this, ever since she was a girl, growing up in post-war Britain during a time of rationing and a scarcity of materials, when it was normal to make do and mend. Her bags are beautifully sewn and lovingly constructed. I spoke to her about an idea I had for a bag of my own and she understood immediately what I needed, my old bag was falling apart and she could help not just revitalise it but rethink it. OK you might think but isn't this craft and not art? Perhaps there is an infinitesimal line between the two, but her remade bags are also ideas and she had very clear convictions about sustainability and the need for recycling, so it could also be argued that these objects did reflect an ideas base and that they contained within them a very clear point of view. The craftsperson is thankfully still with us and is still envisioning ideas as well as making them.

I was reminded of these distinctions when looking at the recent work of the artist Matteo Rattini, who has trained a neural network to create images of contemporary sculptures based on Instagram's algorithm suggestions. Basically he fed into a computer hundreds of images of modern sculpture and asked it to come up with a range of ideas based on the information it had received. These ideas were realised as 3D images using a CAD package and exhibited on screen as virtual sculptures.

These are drawings, very convincing drawings yes, but they are still drawings. Once again I would argue 'disegno' or the use of drawings as the basic building blocks out of which a finished concept can emerge, is being used. Just as in the same way that Michelangelo would show his 'finished' drawings to prospective funders, in order to raise funds to get sculptural ideas commissioned, Matteo Rattini could use these images to persuade someone to fund their realisation by 3D printing.

Thoughts about how a drawing allows the imagination to leap forward and how it can envisage a possibility are conflicted and yet stimulated by Rattini's work because his images look as if they have been already built and then photographed. But they have not, the visualisation process still doesn't do the work for you, someone will still have to carve that sculpture or get it made in some way. However that 'get it made in some way' has changed and these could be 3D printed. The virtual models are produced in such as way that every facet is recorded as a set of coordinates and these coordinates can be used to drive a 3D printer. If it is sent to be printed, the hand skills normally associated with crafting a work of art are redundant, replaced by a machine, at the moment still serviced by a technician but a machine nevertheless. But does this matter? Isn't the idea more important?

I'm sort of mixing up two things here, the need to validate art as an intellectual activity, one that is about ideas and their realisation and the need to recognise the importance of material thinking. I'm hoping that materials might have embedded within them something that links to very old animist ideas, ideas centred on the vitalist nature of materials. Remember that Michelangelo saw his ideas in the marble and carved until he set them free.

But we can also see the potential of 3D images within 2D drawings, some drawings are though harder to use to visualise 3D figures than others.

The centuries-old art forms of origami (folding paper) and kirigami (cutting and folding paper) offer elegant solutions to this 2D to 3D problem, involving only folding and cutting to transform flat papers into complex geometries, but the more humble art of making flat templates for soft toys is also part of this tradition.

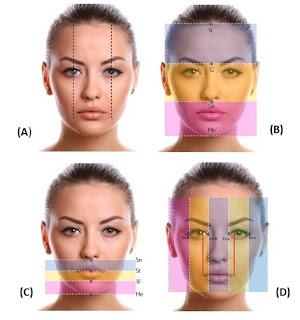

All of these issues become conflicted however as they enter the world of data manipulation. For instance the company Lalaland uses AI to create synthetic humans for fashion eCommerce brands, this is used to increase diversity in retail. Lalaland’s platform generates human like models of different ethnicities, ages, and sizes, customised according to customers’ body shapes, such as hourglass, apple, triangle, pear, or rectangle. A highly efficient automated workflow combines on-mannequin product shots with AI-generated model imagery to produce realistic model images, created in a fraction of the time required by traditional model photography. I.e. there is no need for an actual human model any more. In my earlier blog post on surfaces and body perception I looked at the process of measuring the body and creating a flat structure that could then be converted into a digital 'human', but now things have moved on; or have they? If you read the last post, you will be very aware of the issues I have with measurement and the collection of data.