3,400-Year-Old Ancient Egyptian Painting Palette

Made out of a single piece of ivory, the artist’s palette above has six oval paint wells that still contain cakes of blue, green, brown, yellow, red, and black pigments. At the top end of the palette is also the inscription of the pharaoh Amenhotep III in hieroglyphics, coupled with the phrase, “beloved of Re.” This was an important object, and the colours within it meant something special. Painting involves making images emerge from the ground up colours of the earth and as such there is something magical about the process, so no wonder the Egyptians wanted to link this palette to Re, the god who personified the sun and who was the creator god, that brought himself and the rest of the pantheon into being at the beginning of time. He was also central to the ideology of kingship and the acolytes of Amenhotep III, would have been very aware that in identifying Re on this palette, they were linking together the concept of divine creator and the protector of the pharaonic dynasty. In such a humble object the idea of the transformative power of paint is seen as mythically important.

There are two intertwined histories of the artist's palette. The first one is a history of the materials behind pigment production and the other one is a history of the surfaces that artists have used over the years to mix pigments on in order to get the colours and consistences needed to make their various paints. You can see what I'm getting at if you look at old palettes and how the colours are set out on them.

Constable's lime wood palette

Rembrandt's palette

I suppose you might wonder why a blog about drawing needs to reflect on this key aspect of painting, but as I have often pointed out, drawing and painting are so inextricably linked that it is hard to separate out the aspects that belong to drawing and those that belong to painting. In this case I'm wanting to talk about an idea of mixing, of taste and the development of a shape, much of which is visualised in my mind by drawing rather than painting and I am also trying to play around with a few ideas associated with drawing as disegno. Disegno, the Italian word for drawing and design that involves both the ability to make the drawing and the intellectual capacity to invent the design, so in this case the design is that of the artist's palette, but its invention, or you might say 'the design process', is where my interest lies.

Paint set out in shells

The earliest written description of palettes is in the accounts of the Duke of Burgundy in the late 1460s, they are described as 'trenchers of wood for artists to put oil colours in and to hold them in the hand.' Medieval painters at work used pigments in shallow shells or saucers, often with a range of colours, such as those set out in the nine saucers or are they shells, of a fourteenth-century illuminated capital from an English encyclopaedia above. A trencher (from Old French tranchier 'to cut') was a type of tableware, and was the forerunner of the plate, a place where you cut food up. It was originally a flat round of usually stale bread used in a similar way to an absorbent plate. Those of you who have eaten Ethiopian food might have come across injera which can be used in the same way. By the end of the meal, the plate will have soaked up all the excess oil and juices, so that it would in effect be the pudding, eaten as a final part of dinner. The rich would give these soaked bread pieces to the poor as alms. The trencher gradually evolved into a small plate of metal or wood, typically circular and completely flat, without the lip or raised edge of a plate. Trenchers of this type are still used, for example, the cheeseboard or a food chopping board, which of course retains in its usage the original Old French, tranchier 'to cut'.

A contemporary cheeseboard

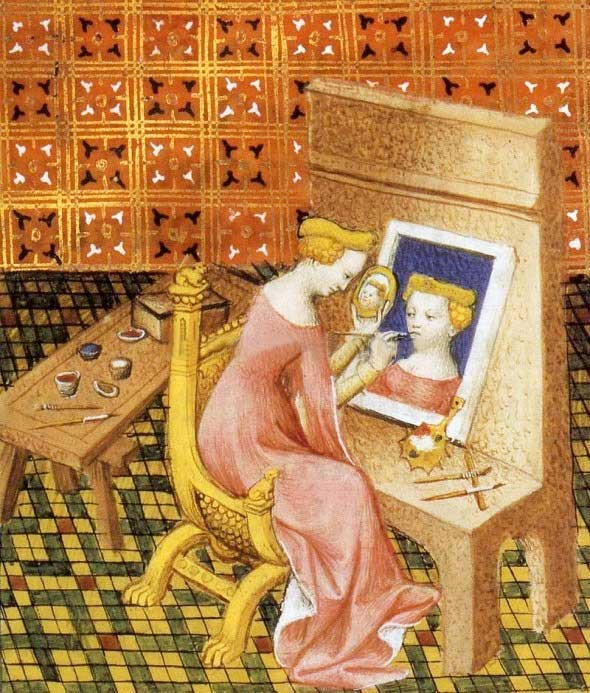

If you look at the wooden cheeseboard above, you will see that it is very similar to the palette in Marcia's left hand in the image below. I'm betting that in those days the same item might have been used for both purposes, and if you have ever had to cut a runny camembert with a cheese knife, I suspect the action would be virtually the same as cutting through a dollop of a stiff mix of oil pigment with a palette knife.

The setting out of the palette, a portable surface upon which colours are arranged according to an artist's interest in particular tonal or colour ranges, has all sorts of implications for the way we think about painting and the main records we have of their use is from images of palettes in paintings made by artists that used them, therefore you might suppose that they were very accurate representations, as they were used by them every day.

Marcia as both painter and sculptor

Marcia using an elongated oval palette

Marcia, painter: Miniature from a manuscript of Boccaccio's De Mulieribus Claris, France, early 15th century

'She devoted herself completely to the study of painting and sculpture; in the end, she was able to carve ivory figures and to paint with such skill and finesse that she surpassed Sopolis and Dionysius, the most famous painters of her day. Clear proof of this is the fact that the pictures she painted were sold for better prices than those of other artists. And what is still more extraordinary, our sources say that, not only did Marcia paint extremely well (a fairly common accomplishment), but she could paint more quickly than anyone else'.

It is possible to guess from some palettes what medium they were using, the palette in the 15th century miniature suggesting an oil medium, a technique only just invented and unknown at the time that these women were supposed to have worked as artists. The paint on the palette of the painter in these illustrations probably has the viscosity of oil paint, which is thick and stiff, as it remains in place on an inclined surface. In this miniature, Marcia also has paints set into shells on the table next to her, their small size suggesting that they were chosen pigments decanted from a pig's bladder which was often used to store larger quantities of paint. She is perhaps using the palette more as a mixing surface than as an orderly array of colours that will help in her tonal or colour range selection, and if this was the case, the artist may have spent more time ordering the pigment filled shells when choosing their 'pallette'. Marcia is depicted as a Medieval woman but in Boccaccio's text we read that she was a Greek artist from the 1st century. The palette she uses has a long handle and she rests it against the painting she is engaged with, as she needs her free hand to hold a mirror. For myself the painting is fascinating because as well as being an early indication that women used to be taken seriously as painters, it has several layers of reality. The face in the mirror, the painted face and the side view of the artist's face, all exist at the same time, in the same reality, in effect the artist Marcia, now exists in triplicate. Marcia was also a stand in for someone else, Boccaccio based his story on a much earlier account by Pliny, who wrote about a famous female painter from ancient Greece called Iaia of Kyzikos who Pliny states, ‘painted a portrait of herself with the aid of a mirror’ which would of course have been a bronze mirror in her case. The miniature of Marcia at work from the middle of the 15th century appears to duplicate Marcia even further. The stance she paints of herself is further reflected in her sculptures, as if once she had made an image of herself, she then used it as a model for all her sculptures of women. Marcia in this way becoming an icon of reproduction, even though, or in spite of the fact that as Pliny also stated, ‘she remained single all her life’.

Boccaccio's text also celebrates the lives of two other women artists, Irene, daughter of Cratinus, who 'surpassed her master in art and fame' and Tamaris, daughter of Micon, an Athenian artist.

A 5,000 year old ox shoulder blade used for digging

If you look at the palette used by Marcia in the early 15th century image, you will see it consists of a handle and a broad flat surface to lay colours out. I would suggest the form came to us as humans a while before the medieval period and at least 10,000 years before these women painters were meant to have practiced. Long before the kidney shape I'm sure the scapula was a model for the palette, a place where colours could be mixed and I'm also sure shells have been used as vessels for keeping pigments ready for use for thousands of years.

Human scapula

I can see in the scapula the possibility of a palette and so I'm sure would early peoples.

A contemporary kidney shaped plastic palette

This plastic palette above even has small scooped out indentations, memories of shells, set out around its perimeter.

Think about how you lay out food around your plate. You don't just dollop it on, you carefully arrange it, often with concern for colour, but more often concern for mixing one taste with another. You will put mustard near to meat for instance, because you know a mix of the two excites your taste buds. Is not the laying out of an artist's palette similar? As you lick the ends of your brush to ensure a fine point, perhaps you are much closer than you realise to being a colour chef or paint cook and that kidney in your hand is as much a food stuff as a mixing surface.

Van Hemessen has an interesting palette, she holds it at an angle that makes you think she wants to show it to us. She has a very small palette with few colours on it and there is no mixing going on. In Cennini's craftsman's handbook he states that if you wanted to paint flesh you first of all painted in a green underlayer, "Take a little terre-verte and a little white lead, well tempered; and lay two coats all over the face, over the hands, over the feet, and over the nudes." The flesh tones were applied over this underpainting. You had to make up three values of flesh colour, each lighter than the other and then you would lay each flesh colour in its place on the areas of the face and to do this the flesh tones were pre-mixed in a system of three gradations, which corresponded to the three modelling planes of light, mid-tone and dark. Blending was then done on the picture surface, rather than mixing on the palette. Cennini also describes preparing colours for painting clothing or draperies and again he tells the artist to set out a series of three basic tones onto the palette and blend afterwards.

The kidney with violet

Caterina Van Hemessen, Self-Portrait, 1548

Niklaus Manuel Deutsch, Saint Luke Painting the Virgin, 1515

Nb. A few thoughts about words. Words are interesting things in that they hold onto the edges of events and turn complex interconnected processes into simple chunks so that we can understand them, especially as nouns. But they can also develop a series of poetic associations some of which are based on homonyms. Homonyms can be homographs, (spelt the same but meaning different things) or homophones, (sounds the same but means different things) or both. Even though you know these words stand for different things, because they sound the same, your instinctive self feels that there must be some sort of connection between them. Set out below are a few palette/pallet/palate meanings.

A “palette” as we have just seen is the flat board an artist mixes paint on, and by extension it also means a range of colours, as in, "The artist's palette consisted of reds, greens and blues" and it is associated with the tools of the artist, such as a palette knife. Derived from the French palette, which in turn comes from Old French palete, a "small shovel or blade". This in turn comes from the Latin pala "spade or shoulder blade".

A “pallet” is a type of bed made of straw or hay, used in medieval times. Close to the ground, it was generally a linen or some other material sheet stretched over some hay or straw. The mattress might be called a palliasse, or sometimes pallet, based on the French word for straw: paille.

A pallet is also a wooden platform used as a base for storing and shipping large items. This word is also derived, like the artist's palette, from the Middle French 'palette' (literally, “small shovel”). This small shovel has led to a variety of mixed meanings. Hence, a pallet was also a flat flexible wooden blade, an instrument with a handle used by potters for shaping. There is a related original sense in English which was medical, such as a pallet being "a flat instrument for depressing the tongue." These are now however called spatulas and are normally made of wood. However as we have seen a palette knife is designed to clean and scrape your artist palette and it has a straight blade made from metal with a wooden handle or plastic with a flexible blade. However a spatula can also be used to mix your paint and is usually described as a flat thin implement used especially for spreading or mixing soft substances.

A spatula for tongue depression

A spatula for cooking

A spatula is any tool with a blade that is somewhat flexible, but fairly rigid, so in effect a palette knife is a type of spatula. However a 'palette' is a “small shovel” which could look very like the wooden spatula used for cooking. Gradually 'pallet' became the spelling for a "large portable tray" like a cheese board and in extension, eventually becoming the spelling for the usually wooden flat crate like support used with a forklift truck for moving loads.

In heraldry a pallet is a vertical stripe, half as wide as a pale.

The palate is divided into the hard bony palate and the fleshy soft palate. The palate is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals and it separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. This derives from the Old French palat and directly from Latin palatum "roof of the mouth," also "a vault," which is perhaps of Etruscan origin [Klein], but de Vaan suggests an IE root meaning "flat, broad, wide." It was popularly considered to be the seat of the sense of taste, hence transferred meaning "sense of taste" (late 14c.), a term also used in this way in classical Latin.

Words begin to loosen their hold the more you play with them, and it is useful be be reminded that they are a convention for shared meaning and in no way have any relationship to reality.

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment