An old memory drawing test exercise

Memory drawing used to be a vital part of an artist's training. The image above is of a glass slide found in a skip in Newport recently. I would have been really interested to have seen what the rest of the slides looked like, but this found image conjures up a pretty good idea of how one particular examination worked.

Many years ago I read a biographic novel about the life of the artist Gainsborough. In the novel, (whether this was based on fact I don't know) Gainsborough had set up a still life in his cellar and had put a canvas on an easel in his attic. He hated climbing stairs, so this meant that if he was to minimise his climbing time, he would have to memorise the still life really clearly when down in the cellar, so that painting time in the attic was productive. This scenario has stayed in my head, so it must have had some use as a mnemonic. When I tried to work with the same situation myself, I found it almost impossible to carry in my head the necessary detail to make a good accurate drawing in the top floor studio. The process of climbing four flights of stairs demanded a lot of physical effort and this seemed to drain away the energy needed to hold an image in the mind. Like many things, if you are to develop the muscles, (both physical and mental) you need to train regularly.

However there are many other ways of developing memory as a useful mechanism in relation to image making, most of which involve the image maker providing helpful memory frameworks for the audience. This being the case, I would like to remind everyone who is making drawings or images of any sort, that visual memory training is a discipline with a long tradition and that it is one well worth looking at if you are to become more astute when making decisions as to how your images will become memorable.

Drawing on paper from Mogao Caves

In the past our own bodies have often been used as memory machines, and they are much easier to work with than full blown memory theatres as described in Frances Yates' wonderful book, 'The Art of Memory'. A book that everyone should read, simply because it helps us to understand how our brains need structures within which to save memories and even more importantly, that memory structures need images associated with them if they are to become 'memorable'.

Guillo Camillo's Memory Theatre

Memory theatres are though huge and costly things and there are other ways to achieve similar ends, in particular our hands can be used very like mini versions of these theatres, fingers replacing the aisles that were placed between rows of information seating. The process of bringing together certain associations or particular images in order to trigger memories, quickly begins to create bizarre forms, and hands in particular seem to lend themselves to both imaginative play and to support materialised thinking in relation to numerical ideas and visual representations of structural principles.

One of the most ambitious of hand mnemonics was presented by Girolamo Marafioti of Calabria in a 1602 treatise on the arts of memory. The system consists of a map of ninety-two manual loci; twenty-three on the front and back of each hand, each housing a different geometric symbol: a crescent moon, a chalice, a circle with horns and what looks like a lemon. To use the system, one assigns a to-be-remembered thing to each locus. One might, as Marafioti suggests, use it to remember a group of people arranged by status, age, or other characteristics. The system compresses the features of a memory palace and makes the whole edifice fit into the shape of a hand.

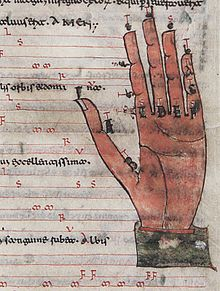

From Girolamo Marafioti’s 17th-century treatise on the art of memory, De Arte Reminiscentiae, demonstrating the use of loci

Using hands to visualise numbers of days in months

We have all played this one:

Here's the church and there's the steeple, open the doors and there's the people

What began as a post to remind everyone of how important visual memory is, is now becoming a post about hands and how they can become the starting point for memorable image invention. So I'll save the stuff about artists' visual memory teaching for another post and look at hands and how they have been used as memory devices. Yes my mind flits around all over the place, but it's the way it operates best for me and hopefully, eventually all these diversions will make some sort of sense.

The hands (above) of the Chinese image from the Mogao Caves were drawn over a thousand years ago and are annotated with Chinese characters on the fingertips that give a specific name to each digit; above that, on a second row we find the names of the five Buddhist elements: space, wind, fire, water and earth and a final tier, floating upwards as if on kite strings, lists the ten virtues. The drawing illustrates a mnemonic system, that helps the viewer to make connections between elements and virtues. At about the same time in England, the monk Bede came up with a treatise called 'The Reckoning of Time', in which he laid out a method for determining when Easter would fall on any given year. These two systems both deal with the issue of materialising thought. As Barbara Tyersky puts it, "When thought overwhelms the mind, the mind puts it into the world". Those of you that regularly follow this blog will be well aware of how important I believe 'materialising thought' is; without a way to externalise thought we become trapped in our own minds and making images is one of the best ways of doing this.

Bede. Diagram from 'The Reckoning of Time'

In ancient Pompeii a bronze sculpture of the Hand of Sabazius held images of protective symbols for the house owner. Sabazius, the god of vegetation and the guardian of women in labour, is often depicted in the palm of a hand, but it is the other symbols that emerge from the hand including a nursing mother, a crow, a table with offerings and a serpent, that make these hands such fascinating objects. These strange hands are memorable precisely because of the fact that they are strange, but their strangeness is one driven by a very normal desire, the need to seek divine protection.

Cicero wrote about the importance of memory as an aspect of rhetoric and he introduces us to the idea of memory devices and provides a lasting image with which to remember how memory devices work. Cicero connects the training of memory with sight and like other classical rhetoricians he used the mind’s recollection of visual space to act as a guide to the memorisation of ideas. A mythic story of the invention of the art of memory by the poet Simonides, is told by Cicero and as it not just describes how the art of memory works, it is itself a memory device, I shall repeat it again.

The poet Simonides created the art of memory when, after he was the lone survivor at a crowded banquet, he was asked to identify the bodies. During the banquet, he had been asked to step outside because he had to receive an urgent message. While taking the message, there was a rumbling sound as an earthquake shook the building, the roof then collapsed, crushing everyone inside beyond recognition. Simonides was shocked but safe. Very soon the distraught relatives of the other diners arrived at the scene and according to custom they needed to bury their dead relatives within the day, but there was a problem, the diners had been badly crushed and disfigured, so no one could tell who was who. Simonides however came to everyone's aid, he had a way of remembering the names of all the corpses by remembering who was sitting where. The shape and layout of the room and its tables and chairs were clear to him in his memory and as the people in the room were of great importance, their positions in relation to the room's layout had been sharply impressed upon his mind.

This association with location, meant that many early memory methods involved walking around a building and things that were to be remembered were then distributed around the building in significant places and you walked through these spaces in your mind, each location triggering a memory because something was positioned that was designed to set off an association with what you were trying to memorise. The hand is like a small building and can be used in the same way.

I have looked at hands as a way of remembering musical notation in an earlier post, but a good idea is always worth revisiting. In this hand image (below) made in response to ideas supposedly set out by the 11th-century Italian monk and music-theoretician Guido from Arezz, we can see how he uses the hand image to memorise the names of tones and their relationships by linking them to the natural divisions that we make when drawing hand images.

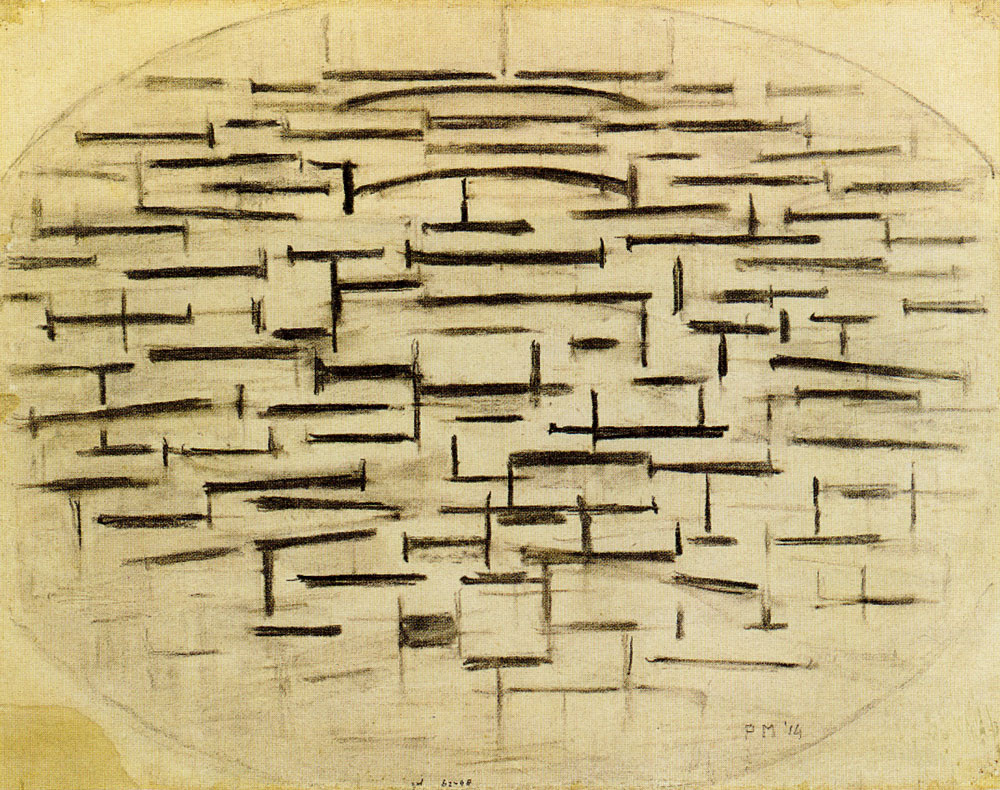

16th-century diagram from the manuscript of an unknown author depicting musical notes scored across a hand in the method attributed to Guido

Manuscript illustration of a 'Guidonian hand' 1274

The solmization sequence ut-re-mi-fa-sol-la appears both on the enclosing circle and on the hand itself

In the drawing above the artist has been able to break totally away from normal conventions of spatial depiction, The near hand is big and powerful, but the far hand is gigantic, it spreads out until it is big enough to contain the idea.

It's amazing how different hands can become. The one above also illustrating Guido's ideas could belong to an Egon Schiele of the Medieval artist world.

Egon Schiele

These woodcuts of chunky hands below, are totally different in sensibility. They are heavy and solid, the sort of hands that if engaged in making karate chops would do some serious damage.

From Anianus’ Compotus cum commento (1492), an adaptation of Bede’s computus system

Van Gogh: Hands

Van Gogh's drawing of hands, is an image of hands that know how to do hard work; these are peasants hands. Whilst the hand below is meant to be much more spiritual. Hand-coloured woodcut: The Hand as the Mirror of Salvation

El Greco

El Greco's hand above, is a fascinating one. It is in fact quite strong, and yet at the same time it is sensitive and definitely a hand that has spiritual intent.

From Stephan Fridolin’s 'Treasury of the true riches of salvation': 1491

The hands above contain numbers that correspond to meditations in the book, in effect creating a table of contents. I like these hands as the little fingers have a kink in them, and so do my own fingers, a fact that makes me think that the artist, may have like myself, had arthritic fingers. However in the same book, we have a pair of more solid hands, hands with much broader fingers that can carry busts of the apostles, saints, Mary and Christ. .

From Stephan Fridolin’s 'Treasury of the true riches of salvation': 1491

Of course we can use our hands for many other purposes, they are as versatile as we want them to be. From the shadow puppet of childhood to the fist of adulthood, the hand morphs into what we want it to be. As in the case below where the hand becomes a 'handy' sundial.

Thoinot Arbeau 1582 volume of practical astronomy: How to convert the hands into a sundial

For the people of Michigan, the hand becomes a map.

You are supposed to know something really well if you know it like the back of your hand. A phrase I never really understood. As a boy I had spent many hours with my gran who would often hold my hand and carefully trace out my lifeline or prod my Venus Mount, she seemed to know all there was to know about the palm of my hand, but she never spoke to me about the other side.

Chart of the Hand from Dr Alesha Sivarth's Book of Life 1898

References:

Tyersky, B. (2019) Mind in Motion: How action shapes thought London: Basic Civitas Books

See also: