Anthony Gormley

We are always advising you to draw more. But why? There is an aspect of drawing called 'iterative' which means that drawing is centred around trailing and testing and making variations. This allows you to discover what works and is at the core of what you need to do in order to find new imagery. It also gives essential time to the development of skills. In essence hours spent doing things leads eventually to a command of your language. John Cage wrote 10 rules for students and teachers and at their core are 'There is only make' and 'The only rule is work'.

Another key rule from the list above is 'Do not try to create and analyse at the same time'.

However trailing and testing and making variations is not just a process of unthinking making. Every now and again you need to look at what you have done and make decisions about it. Joseph DeFazio in 'Designing with precedent: A cross -disciplinary inquiry into the design process' (2008) refers to Goldschmidt's distinction between drawing as 'seeing that' and as 'seeing as'. 'Seeing that' incorporates the process of reflective criticism and 'seeing as' represents the process of making referential analogies and interpretations. He sees this as a type of conversation and negotiation. Goldschmidt (1991) intimates that drawing is an iterative process that materialises towards a final product and can include intuitive inductive loops that cross cut through any existing body of information. He has another mantra; 'Draw, re-draw: test, re-test'.

However it's not all about new information. Schon and Wiggins (1992) have a theory of the displacement of concepts, in which you use old existing information in the creation of the new. Old concepts and working practices are restructured in relation to new situations. I.e. the more you have done in the past, the more you can draw upon these experiences to construct new ideas in response to change.

These ideas about visual thinking come from research into designers drawing, mainly because designers are thought of as people with visual problems to solve. Artists also have problems to solve, but perhaps without the pressure of an outside client. I say 'perhaps', because in reality artists have just as many outside pressures to resolve what they are doing as designers. For instance I have just been given a commission to install a site specific work in the grounds surrounding York City Art Gallery, this involves various types of drawing, both imaginative and practical, as well as lots of site testing to make sure what I make will work when placed in situ.

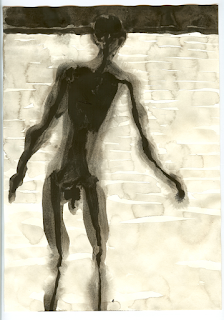

Two of my working drawings for York City Art Gallery project

In Richard Sennett's 'The Craftsman' he points to the fact that making exemplifies the special human condition of being engaged. He goes on to state that skilled craftsmanship needs about 10,000 hours of experience to enable the maker/drawer etc. to reach a level of competence whereby they can become much more problem-attuned, whereas people with lower levels of skill struggle just to get things to work. When a skill is fully developed its technique is no longer just a mechanical activity; the maker can feel different levels of expression and think much more deeply about what they are doing. They in effect become tuned into the materials they are working with. They don't separate themselves from what they are doing, they are in effect part of the process. A good craftsperson knows their own body and how it operates and senses how it can enable the materials used to flow into forms that 'arrive' through the process of making.

Juhani Pallasmaa looks at how touch gesture, habit and intuition are essential to our understanding of space and materials, he explores how the hand operates in partnership with the eye and the brain.

I pointed out in an earlier post that material thinking is now becoming more and more important. This is because there is a reaction against what was called 'the linguistic turn' and then a further reaction against something called 'the cultural turn'. The basic argument is this. Although it was useful for us to think about the world in relation to our codes of communication (seeing everything as language and therefore analysing it in terms of semiotics) or in terms of cultural production, what we were in effect doing was ascribing human centred thinking to everything else; animals, plants, materials, objects, etc. We had developed a view of the world whereby the conceptual frameworks we were working with put ourselves at the centre of operations as if we were the most important things in the world and usually our concepts didn't just place us at the centre but also at the top of the pile. We elevated our own concerns, our own timescales, our own ways of being as in someway being of much more importance than anything else. We have of course recently had to rethink this. The world itself is fighting back, we begin to realise that we should have been working sympathetically with the world and not mining it for its resources and polluting it with our waste. We have slowly begun to realise that if we don't change our viewpoint the world will work to erase us. Only by being in harmony with the plants, animals and materials that we co-inhabit with on this planet will we survive, and if we are to do this we need to change our conceptual frameworks in order to become inclusive of not just others like ourselves but minerals, energy flows, organic and inorganic forms.

Artists have a responsibility to think about these things as well as politicians. But small changes begin at a local level, and a first step might be a reflection on what it is to make anything. By asking a basic question such as 'how can we be sympathetic to a material?' we open the door to a series of rooms that have perhaps not yet been explored. This basic question may lead you to ask others, such as 'how does an awareness of the wider ecological or environmental issues affect your choices of action?' or 'how many recent political decisions are actually the result of climate change?' Do we anthropomorphise our concepts or not? Perhaps by doing so we place feelings in and with things other than ourselves and thus have a better link with them. A child may play with toy animals and grow up to love real animals.

Immanuel Kant said that "the hand is the window into the mind," but the nature of materials allow the hand to be what it is. Oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen make up 96% of your body mass. The other 4% of body weight is composed almost entirely of sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, iron, phosphorus, sulphur, chlorine, iodine and silicon. Oxygen and hydrogen are fused together in the form of water, which itself allows for the dissolving of other elements into it, in effect recreating an ancient sea inside a walking container. Early single celled organisms extracted calcium carbonate from those seas to create shells and now similar processes create bone. You are a product of material flow, the material flow is not a result of human decision making but humans can make a decision whether or not to 'go with the flow' or to interrupt it.

Therefore we both need to choose a suitable material and become tuned into the chosen material we are working with. You cant really separate these things out, they are in effect part of the process. In Gormley's case, these drawings a made with dissolved pigments in water, which means that we could read them as being metaphorically connected to the idea of the body as an ancient sea inside a walking container. The more drawings he makes, the more variations on this theme revel themselves, the body dips into and out of the pools of pigmented liquid, sometimes its edges are sharp and clear and at other times they begin to dissolve back into the paper surface. Personally I think these images could be taken much further, but of course I'm sure he has at some point, because he normally makes lots of variations, most of which we wont see.

Anthony Gormley

'Hopefully it gives you an opportunity to put yourself in the place offered by this silhouette and to think about your connection to and dependence on the context in which we find ourselves... the most important being the elemental world that we have managed for the first time ever, for any species, to have destabilised.'

“Short termism is the way capitalism works and the way politicians work and capitalism is not going to solve this. We have to find another form of defining value that is not market value.

“Nobody wants to face the truth that actually air, water, sunlight are resources that are certainly not free.” From: The Guardian.

In Gormley's notebook pages below again we see him exploring variations, but this time of human figures made up of lots of small units. The metaphors are now very different to the dissolved pigments in liquid. These figures seem to belong to the built environment rather than being things that have evolved out of primeval seas. The individual drawn marks carrying the metaphorical weight of these images.

Coda:

A very clear example of iterative drawing can be found on Jen Roper's website. She is an ex-student of the Leeds Fine Art Degree Course and has recently been selected for the Contemporary British Painting Prize.

References

This podcast is a very good introduction to what has been called 'the material turn.

Rebecca Jane Bennett’s book Vibrant Matter is an excellent introduction to the issues surrounding the material turn, as well as Karen Barad’s (2001), "Re(con)figuring space, time, and matter", which has a more feminist perspective.

Goldschmidt, G., 1994. On visual design thinking: the vis kids of architecture. Design studies, 15(2), pp.158-174.

The Craftsman by Richard Sennett is available as a pdf here

The Thinking Hand by Juhani Pallasmaa is available as a pdf here

An article on Anthony Gormley's drawings

See also:

material thinking

On not knowing and paying attention a talk by Tim Ingold

Letting things happen Heidegger and concept of ‘at hand’

Drawing and philosophy (More on Heidegger)

Drawing and Heidegger

John Dewey Experience and making art

Coda:

A very clear example of iterative drawing can be found on Jen Roper's website. She is an ex-student of the Leeds Fine Art Degree Course and has recently been selected for the Contemporary British Painting Prize.

Jen Roper: Drawings Jason's Coat

Ingold, Tim. The Textility of Making: Cambridge Journal of Economics. 34. 1 (2010): 91 -

102. Web. 1 January 2014.

Ingold, Tim. Toward an Ecology of Materials: Annual Review of Anthropology. 41 (2012): 427 - 42.

This podcast is a very good introduction to what has been called 'the material turn.

Rebecca Jane Bennett’s book Vibrant Matter is an excellent introduction to the issues surrounding the material turn, as well as Karen Barad’s (2001), "Re(con)figuring space, time, and matter", which has a more feminist perspective.

Goldschmidt, G., 1994. On visual design thinking: the vis kids of architecture. Design studies, 15(2), pp.158-174.

Schon, D.A. and Wiggins, G., 1992. Kinds of seeing and their functions in designing. Design studies, 13(2), pp.135-156.

The Craftsman by Richard Sennett is available as a pdf here

The Thinking Hand by Juhani Pallasmaa is available as a pdf here

An article on Anthony Gormley's drawings

See also:

material thinking

On not knowing and paying attention a talk by Tim Ingold

Letting things happen Heidegger and concept of ‘at hand’

Drawing and philosophy (More on Heidegger)

Drawing and Heidegger

John Dewey Experience and making art

No comments:

Post a Comment