Last night I went to a lecture by Tim Ingold. For those of

you interested in drawing theory, Tim Ingold is an essential read. His books ‘Lines: A Brief History’ and ‘The Life of

Lines’ open out thinking about drawing into the theatre of life itself

and allow you as a maker to invest your drawings with a wide range of possible meanings.

At some point I will go through both these books and provide a summary and an indication

of possible ways to use them. However for this post I’m simply going to put on

record the notes I made during his talk.

On not

knowing and paying attention: a

talk by Tim

Ingold

Because

he had before the talk been working with some of the dancers from the dance

centre, the evening kicked off with a performance by eight dancers, which

consisted of them using contact improvisation techniques to explore how people

could be linked in different ways. From massing themselves up into towers which

could be climbed, to swirling lines of linked hands and running bodies, we were

given an interesting physical introduction to the performative possibilities of

the body in space. Performative drawing is now well established within the

drawing canon and is well theorised, a typical example being this PhD thesis on

Marking Time by Jane Grisewood.

Tim

Ingold introduced his talk with a statement to the effect that what we used to

call ‘wisdom’ has now dissolved into ‘knowledge’ and ‘knowledge’ is now

becoming ‘information’. He is worried about this, as it leads to the

disparagement of ‘truth’. He stated the problem is that the more you know, what

you begin to encounter is your own knowledge. Rather than to seek knowledge

perhaps we should be ‘attending’ to things. To be attentive is to discover

things in the experience of them. He asks the question, “Do we need to know

less?”

In

order to know less, perhaps we need to turn towards the world, to accept it for

what it is, rather than to measure it or categorise it. He reminded us of the

key elements of academic practice. To collect data and from that data to

develop theories of interpretation. However he pointed out that in effect

theory turns its back upon the world. Theory is used to interpret data, and is

he believes therefore always separate from the reality of existence.

He

sees the need for all this data and theory about the need for certainty. In a

world of certainty there can be demonstrable ‘joined up’ thinking. Everything

is joined up, so that you can move from A to B to C to D in an ordered

progression. He drew a diagram like so.

Pointing out that as we move between connected

points most of the surface area of the diamond is not actually touched by the

lines of connection cutting it. We in life, follow a much more winding path, not

so much from A to B but a snaking path following the world as we discover it.

Tim Ingold talked about taking an orthogonal direction, which I read to mean

moving at right angles from a starting point, however I’m not sure he meant it

to be so geometrically precise, I think the snaking line he drew on his diagram

was much clearer.

He

moved on to talk about intention. My reading of this was that he was referring to

intention as understood by psychologists. We tend to believe that human actions

are intentional, we set out to aim for something and in doing so we get an

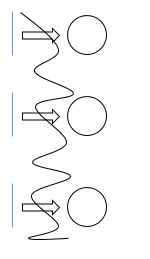

effect. He set out a view of life as a series of aims and their targets,

drawing a diagram like so:

As

each aim and target is achieved we get a sum of actions, each starting with an

intention, and gradually leading towards an objective.

However

Ingold then points out that attention is longitudinal and that it tends to ‘go

with the flow’ or follow the implications of the material you are working with.

Once again he draws his snaky line over the previous diagram.

He now brought in a new metaphor to explain the difference

between intention and attention. We can divide a log in two different ways, we

can cut it with a saw or split it with an axe. When we cut it with a saw we cut

across and through the wood grain, but when we split it with an axe we go with

the wood grain, using its very nature to help split it apart. Again he draw

diagrams. (I keep including the diagrams because this blog is about drawing,

and I think it’s important to demonstrate how drawing helps us think).

Intention the log and saw

Attention the log and axe

When we go with a material, a decision is matured in the

action itself. Decisions evolve in the course of actions. A decision is in

effect a reflection of movement. For example; when walking, you intend to go,

but once you set out each separate step is not an intentional act. “I am

walking” becomes, “My walking walks me”. Every step is hesitant, each footstep

begins with an investigation of the ground and its nature. Like making marks on

a drawing, as we make a series of steps, we are not sure where each one will

go, but gradually one becomes more assured as you find your way. You are though

testing as you act, you need to “push the boat out into the current”, to take an

existential risk in order to do anything at all. This means that you need to be

open to the conditions of the world. You are in effect inside the actions you

take, and it is only afterwards that you can say, “I did that”. You merge with

the action itself.

In the intentional model cognition leads and the body

follows. But in a model whereby we submit to the world, (the submission model),

we are cast off into a world of actions, where skills mastery and vulnerability

are both sides of the same coin. Lines of life, like the emerging delicate

roots of a growing plant are always hesitant. Submission therefore leads but

mastery follows.

This is how Ingold believes the imagination itself works.

Imagination is a sort of improvisation of a way or passage through life.

However as a way is seen, you need the skills to make best use of your passage.

Skill sets therefore follow imagination or insight. It is important not to

think of imagination as a form of mental representation, imagination goes

beyond what we can represent. In fact if we can represent something we already

know what it is; imagination is about what we have yet to represent.

We are asked to think about what it means when something ‘appears’

to you. It is revealed to you. You join with it in the moment of its birth, you

are as much part of the revelation as what is revealed. However this situation

is more likely to take place if you are in tune with the material world you

inhabit. You develop ‘foresight’ when you are at one with your materials. You

sense what they are capable of. Foresight in this definition being not about

seeing something in the mind’s eye, but seeing something as a type of forwards

anticipation, being one step ahead of your material, because you are paying

attention to that material. (You can see here why Ingold is very important for

people who make art, this is a very good description of what happens as a

drawing or other art form evolves). Foresight is the opening up of a path, a kind

of seeing into the future, which allows you to carry on. Foresight could in

these terms be seen as looking towards a possibility.

However possibilities eventually become actions. Ingold

draws another diagram demonstrating the relationship between submission and

mastery. The steep learning curve of submission eventually reaches a point of

what Ingold termed ‘inflection’ (I take this to mean change in meaning)

or a tipping point, whereby an action matures and we move towards mastery.

These tipping points he believes are often between sets of opposites.

Point of inflection

Submission Mastery

We need to educate our attention, and remind ourselves that

in perception there is the constant weighting of the ‘affordances’ of

perceptions. (Affordances are: ‘Action possibilities in the

environment in relation to the action capabilities of an actor. Independent of

the actor's experience, knowledge, culture, or ability to perceive). I.e. are our perceptions useful? If we feel they are not we often ignore them.

Ingold sets out two opposing views of what is out there. Do our perceptions chance upon a world already laid out, or is nothing ready for us, so that we have to be astute enough to respond to what we find, and as we find it we in effect shape it.

The line we cut through existence is open ended, it is more about hopes and dreams, not plans and predictions. We are in effect 'longing for something'. This longing is what hopes and dreams are, and the problem we face is how to capture them, or make them materialise before they get lost. This is of course the artist's fear. The real skill of the artist is therefore that of the dream catcher. The pinning down of an idea, and its realisation is key. However there is always a tension between the anticipatory reach of an idea, and the drag of materials in action. The friction of material engagement is what slows an idea down, but at the same time gives it the chance of realisation. All life is caught in the tension between opposites such as submission and mastery or imagination and aspiration.

Ingold cites the word 'longing' as vital to this understanding, he believes that longing wells up in attention and leads on to a skilful manoeuvre. It is a word that can also be in either future or past tense.

Perception is also about exposure. By willing each step into action, we are in effect pulling ourself out of the position we were in. In exposing ourselves to the world we attend it or wait for it, and in doing this we can be astonished by it. Not 'surprised'. In science, it is stated when something comes up that is unexpected, this is, 'not as previously thought'. The flipside of anticipation. Ignorance presupposes that things have to be explained to us. However what if we are not wanting to constantly anticipate things, perhaps ignorance is best. Prediction depends on concepts and categories, we use data to build theory based on concepts and categories, therefore we are surprised when our predictions are wrong, but not astonished. But those who are attentive to the world are always astonished at what they find, this is due to their vulnerable but resilient attention. This attention should mean that we are more aware of others, both other humans and the world itself, opening out an ability to correspond with others. Each responding to the other in an ongoing conversation, rather than joining up with others.

Ingold then draws another diagram of flowing streams of things moving alongside each other.

The issue he now highlights is the fact that responsiveness is an ethical condition. He goes on to quote from Deleuze and Guattari's 'A Thousand Plateaus', "'One ventures from home on the thread of a tune", a line that suggests both the fragility of experience and the way we need to dance with it.

He goes on to say that thinking unsettles thought. It reaches hesitantly towards something else. He returns to his earlier diagram about certainty and asks is this what we should be looking for? Should we be looking for understanding or what he termed, 'undercommoning', or the moment of being lost. (My understanding of 'undercommoning relates to antiauthoritarian organising groups, so I'm not sure exactly how he is using the word)

Ingold now moves on to suggest that our normal experience is actually more like that of those with autism. Autism is always experiencing the world as it is. Therefore things are always unsettling. However, most of us can from the moment of astonishment move quickly on to normalise our relationship with reality.

Going back to his earlier issue with too much knowledge and in particular scientific knowledge, he suggests that many of our problems are 'fake' problems. I.e. they are problems with existing solutions, such as jig-saw or cross-word puzzles. This he feels is rather like the difference between real and fake freedom. Fake freedom is one of imposed options, such as the recent referendum, binary choices are in many ways non choices. Real freedom is the freedom to decide on a path through life and to follow it no matter how it wavers about, or makes U turns. Freedom and necessity are one and the same thing, it is about harmonising with something to find a direction. Finally he brings us to the current state of education and suggests that it now offers an immunity from experience, rather than an exposure to it. Education offers an illusionary certainty, but richness of thinking only comes from uncertainty. Therefore, in conclusion, not knowing is not ignorance but a form of wisdom, a form of wisdom centred on paying attention to things and not being bound by theory.

These notes were taken during the talk and were scrawled in a small notebook. I apologise for any inaccuracies or misunderstandings, they are all due to my own inability to concentrate or understand what was said.

References:

Ingold then draws another diagram of flowing streams of things moving alongside each other.

The issue he now highlights is the fact that responsiveness is an ethical condition. He goes on to quote from Deleuze and Guattari's 'A Thousand Plateaus', "'One ventures from home on the thread of a tune", a line that suggests both the fragility of experience and the way we need to dance with it.

He goes on to say that thinking unsettles thought. It reaches hesitantly towards something else. He returns to his earlier diagram about certainty and asks is this what we should be looking for? Should we be looking for understanding or what he termed, 'undercommoning', or the moment of being lost. (My understanding of 'undercommoning relates to antiauthoritarian organising groups, so I'm not sure exactly how he is using the word)

Ingold now moves on to suggest that our normal experience is actually more like that of those with autism. Autism is always experiencing the world as it is. Therefore things are always unsettling. However, most of us can from the moment of astonishment move quickly on to normalise our relationship with reality.

Going back to his earlier issue with too much knowledge and in particular scientific knowledge, he suggests that many of our problems are 'fake' problems. I.e. they are problems with existing solutions, such as jig-saw or cross-word puzzles. This he feels is rather like the difference between real and fake freedom. Fake freedom is one of imposed options, such as the recent referendum, binary choices are in many ways non choices. Real freedom is the freedom to decide on a path through life and to follow it no matter how it wavers about, or makes U turns. Freedom and necessity are one and the same thing, it is about harmonising with something to find a direction. Finally he brings us to the current state of education and suggests that it now offers an immunity from experience, rather than an exposure to it. Education offers an illusionary certainty, but richness of thinking only comes from uncertainty. Therefore, in conclusion, not knowing is not ignorance but a form of wisdom, a form of wisdom centred on paying attention to things and not being bound by theory.

These notes were taken during the talk and were scrawled in a small notebook. I apologise for any inaccuracies or misunderstandings, they are all due to my own inability to concentrate or understand what was said.

References:

Ingold, Tim. The Textility of Making: Cambridge Journal of Economics. 34. 1 (2010): 91 -

102. Web. 1 January 2014.

Ingold, Tim. Toward an Ecology of Materials: Annual Review of Anthropology. 41 (2012): 427 - 42.

See also:

Notes on another Tim Ingold lecture

See also:

Notes on another Tim Ingold lecture

thank you for your writing. insightful words.

ReplyDelete