I have posted several times on various drawing media and papers, but one area that is of vital importance to the final look and feel of a drawing is the ground preparation and this post is an attempt to begin to remedy this omission.

All painters are aware of the importance of their ground preparation and it is exactly the same for drawing. In fact many of the surface preparations are the same.

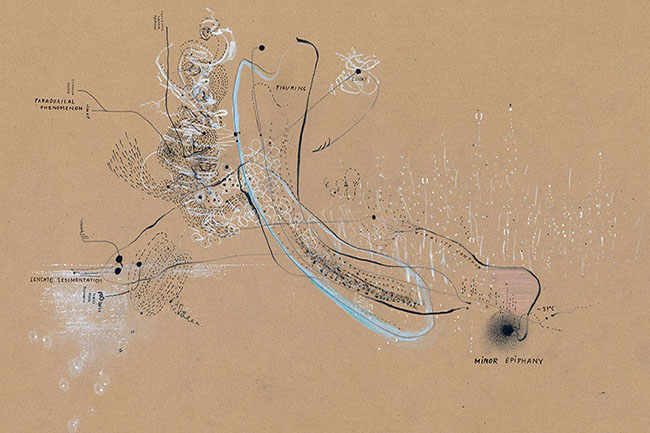

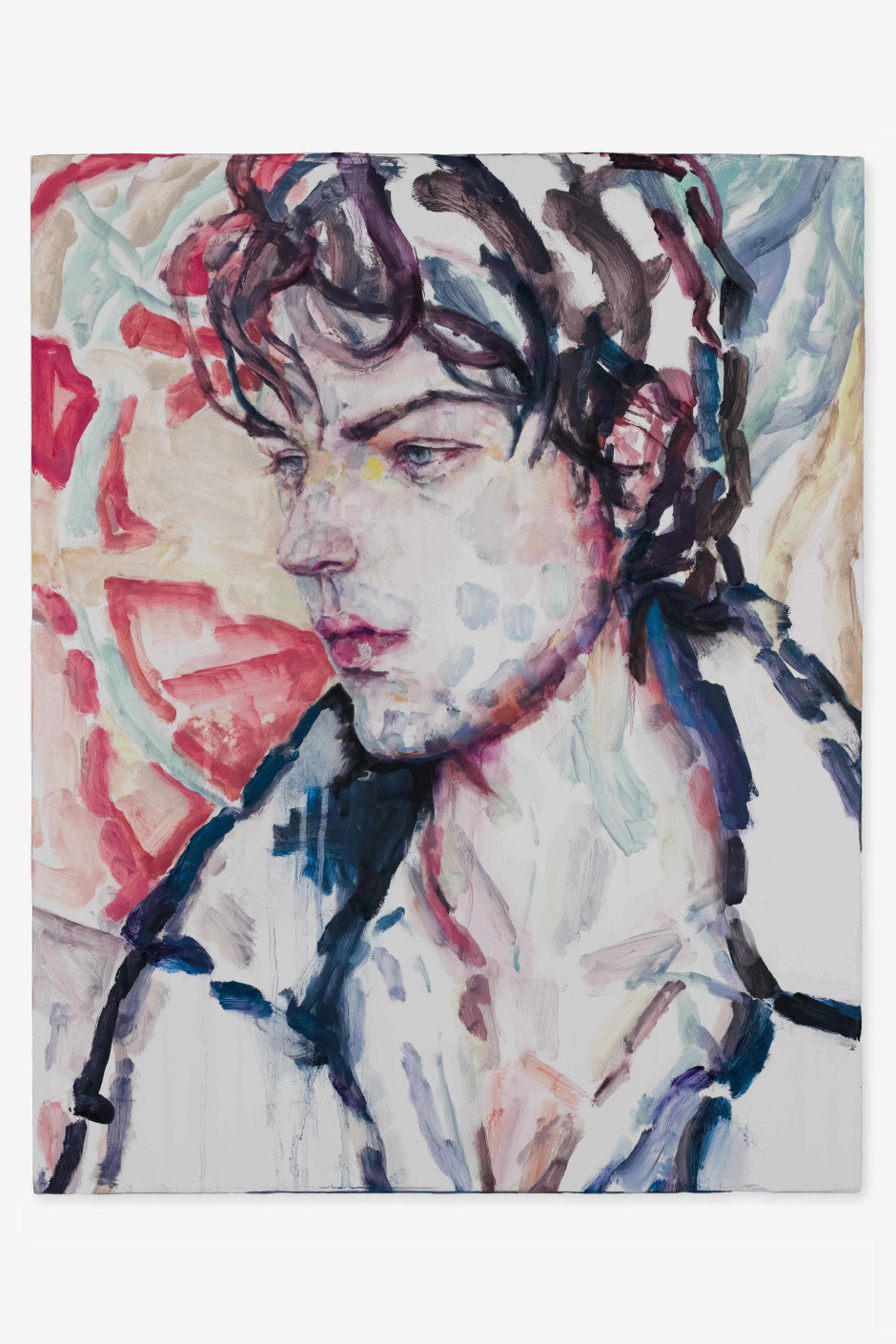

Oil based mark on unprimed paper

However before you begin priming any surface, you might want to consider whether or not the priming is going to support your idea. For instance in the image above you can see how on unprimed paper an oil based mark, such as from an oil stick or mark made with a brush using oil paint, will gradually separate itself out, the oil leaving the pigment as the paper absorbs the oil into itself. This capillary action is of course telling us about the nature of the paper and the nature of oils and pigments. The pigments are suspended in oil and the action of oil spreading out reveals this. It may be that this type of incident is vital to the material message that you want your work to communicate, and if so, you would be concentrating on the type of paper used and its ability to soak up oils, as well as of course on the makeup of the various oil based products that can be used for mark making. On the other hand you may want to investigate priming as a way to generate new ideas. By working across several different surfaces and grounds ideas sometimes emerge from the way the materials operate. But whether you have an idea of an effect you want to achieve, or whether you want to undertake a period of pure research and investigation of possibilities, you will need to use a surface of some sort and paper is for most drawers the one they begin with, so don't forget to check out previous posts on papers which can be accessed at the end of this post in the 'see also' section.

Size

Sizing seals the support, which is why size is also called sealant. Basically size is a glue that seals the paper surface to reduce absorption. The surface sizing of watercolour paper helps watercolour sit on the surface rather than be absorbed into the fibres. This helps to preserve the luminosity of the pigments, whose reflective ability would be compromised by being partly absorbed into the mass of paper fibres.

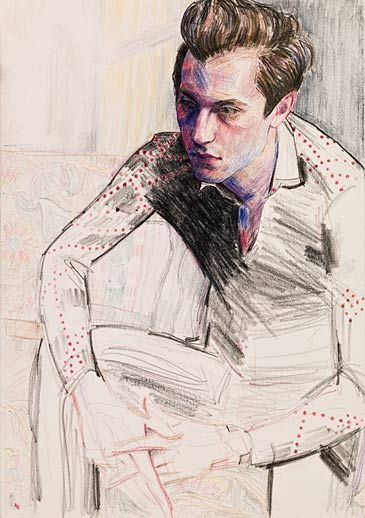

The same brush stroke on sized (left) and unsized (right) paper.

A size can be made from acrylic polymer, PVA, casein, (casein paints are ground in a solution of casein, which is a phosphoprotein of milk precipitated by heating with an acid or by lactic acid) or animal gelatine. The traditional size used by artists is rabbit skin glue, and it is the best if you are looking for a long lasting artefact, because it has a low acidic content.

Primer

Before putting any paint on your surface you might want to use a primer. It is a glue that sticks well to your surface, better than your paint would. Then when your paint is applied, it sticks to the primer, so that it is well adhered, i.e. it isn't going to flake or crack off. Primers for acrylics are often called acrylic dispersion grounds and they are either acrylic gesso or acrylic primer and these new ones made by artist's suppliers such as Johnsons can fulfil the role of a size, primer and ground all in one.

Gesso

Genuine Gesso is made of warmed animal glue and whiting. Gesso is a common preparation for a paper drawing base and has a range of qualities that make it very useful for surface control. You can sand back down into it and in doing so remove areas of drawing in a very subtle way, so that the drawing appears to emerge from the ground, or look as if it is sinking down into it. Genuine gesso is a hard, chalky surface built up by several thin layers. It is sensitive to water and will crack if used on a flexible surface, so to prevent cracking it must only be used on rigid substrates. Genuine gesso is extra-absorbent so it’s the best choice for painting in egg tempera or encaustic. Unless it states that it is traditional gesso, most things labelled gesso, are made with acrylic ground and are not as absorbent as true gesso, so if you can, test out both before making a decision as to which one is right for your particular approach. In drawings mixed with watercolour or dilute inks, the ability of gesso to absorb liquids again comes into its own and there is a deep, saturated look to liquids applied to true gesso surfaces that you cannot get on unprepared paper surfaces.

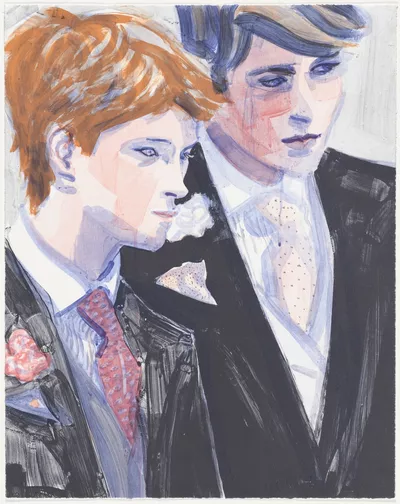

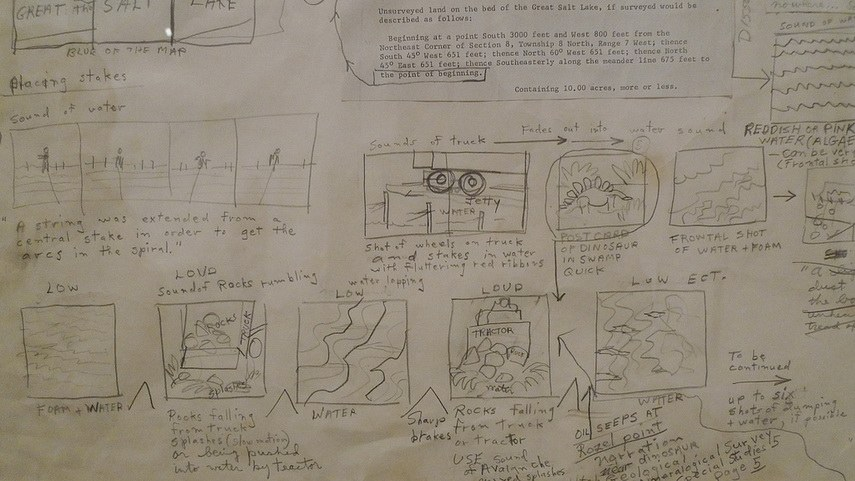

Marks made on gessoed watercolour paper

The paper above was painted using a large brush that left brush strokes using an acrylic gesso. It was when dry lightly sanded to give it a grain and it was then drawn into with a sharp metal point, in order to scratch deep into the gessoed paper. A dilute black ink wash was then applied over the scratch marks and then a clean damp cloth was used to remove the ink from the surface so that it was left concentrated in the scratches. The wiping also enabled the surface to be 'softened' and a further layer of coloured watercolour was then applied and also wiped off.

Watercolour over acrylic ground gesso.

In the image above you can see that the gesso was applied with a big brush in a straight downwards stroke and then put on slightly thicker using a palette knife using horizontal strokes. Watercolour was then applied with a large soft brush and partly removed using a dry cloth.

Many acrylic primers were created to be similar to traditional gesso. You will therefore find various terms such as ‘true gesso’, ‘genuine gesso’ or ‘traditional gesso’, but to begin with just try them out and see what affects they help you achieve. All of them can be painted onto paper, and all of them can then be sanded, scratched into and variously distressed in order to give you textural control over a drawing's surface.

If your surface needs to flex, Sinopia Casein Gesso can be used. It is very absorbent and is the next best thing to genuine gesso. You use it straight from the jar at room temperature. It is made with milk protein (casein) which is a binder in casein paints. It contains a small amount of linseed oil that has been emulsified so it can be thinned and cleaned up with water. But the oil content is actually quite minimal, just enough to make the gesso flexible and water insoluble after it has dried and cured – because it is minimal they say that the surface doesn’t need to be sized first to protect it from the oil. This also means it is not very absorbent, so intense watercolour or ink colours are harder to achieve.

Once the gesso is applied it dries to the touch in a short amount of time so you can apply the second coat the same day when the first is touch dry, but no more than two coats a day. While the surface is stable enough for one additional layer, the oil content has to cure enough for subsequent layers to be applied. Because the recipe includes a linseed oil emulsion it will take four or five days for the surface to cure and become water insoluble. If you are working with aqueous wash techniques, which soak the surface with water, then you should wait for a complete cure. With less water or with oil techniques, the surface can be painted on after a few days.

A ground is the textured surface that all of your various drawing media have to respond to, whether these media are wet or dry. It’s the thing that you experience as 'touch'. Whether it is hard or soft, smooth or textured, absorbent or non-absorbent, coloured or white, it will directly effect the way that a mark sits on a surface. Of course for a painter grounds are also vital, but sometimes the drawer can forget that the paper surface holds 50% of a drawing's textural potential.

Some drawing media have grounds specially made for them, such as pastel and silverpoint. Transparent acrylic pastel primer is a ground that makes it possible to work in soft pastel on a wide variety of substrates: canvas, card, plastic, glass, paper, wood, ceramic or metal. It has a slightly gritty or toothy texture which will hold soft pastel grains. (You also have to think about fixative technology with pastel, so do follow the links at the end of the post for more thoughts on this).

I have posted on silverpoint in the past and in order to get the metal to rub off on paper you need to apply a ground. My first use of a primer to do this was of ground-up cuttlefish mixed into gouache paint. But you can draw with a variety of metals as long as you consider the paper's surface preparation. Metalpoint drawings are made by dragging sharpened wires of soft metal (usually silver or lead, but sometimes gold) over a slightly toothy, textured surface. Particles of the metal wire are deposited on the surface, leaving ghostly grey lines which will tarnish over time to a warm brown tone. There is now a specially prepared commercial ground available, called 'Golden Silverpoint Ground' a milky acrylic ground that is designed for use on porous and flexible substrates.

Detail from Lauren Amalia Redding, ‘De Donde Crece La Palma’ Silverpoint on panel

A good traditional ground is made from rabbit skin glue, bone ash, and pigment, but the rabbit skin glue must be kept at a constant temperature and several coats are required, this is why I used the gouache method. If you want to look at an artist that uses silverpoint grounds really well try Roy Eastland. He combines drawing on gesso grounds with scratching and sandpapering his images away, so that he gains full control of surface possibility.

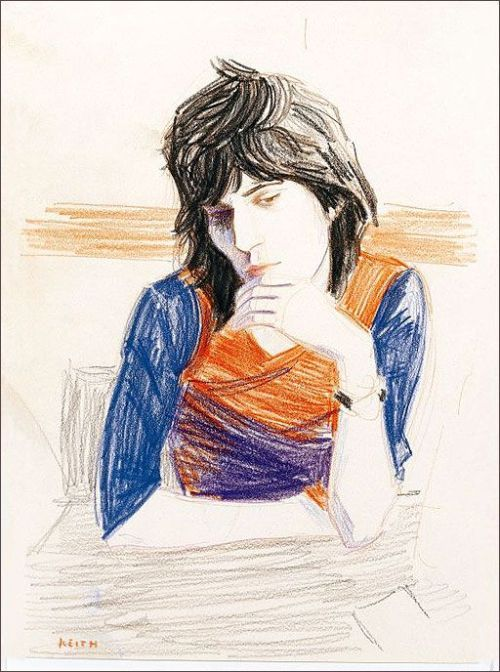

Roy Eastland

Roy Eastland

I particularly like Eastland's drawings of old toys such as the one above, the sanding back of the gesso allowing the images to ghost out of the ground, suggesting that they are emerging out of history.

This post is simply an introduction to grounds and was prompted by the fact that several first year students are beginning to take more care over stretching papers and thinking about how they might use wooden frames to support taut drum like surfaces to draw on, but very few are exploring paper grounds and how they also affect mark making possibilities.

See also:

Charcoal Includes a section on fixative and how to use it Sumi papers A reminder to explore what is out there in relation to possible surfaces to use