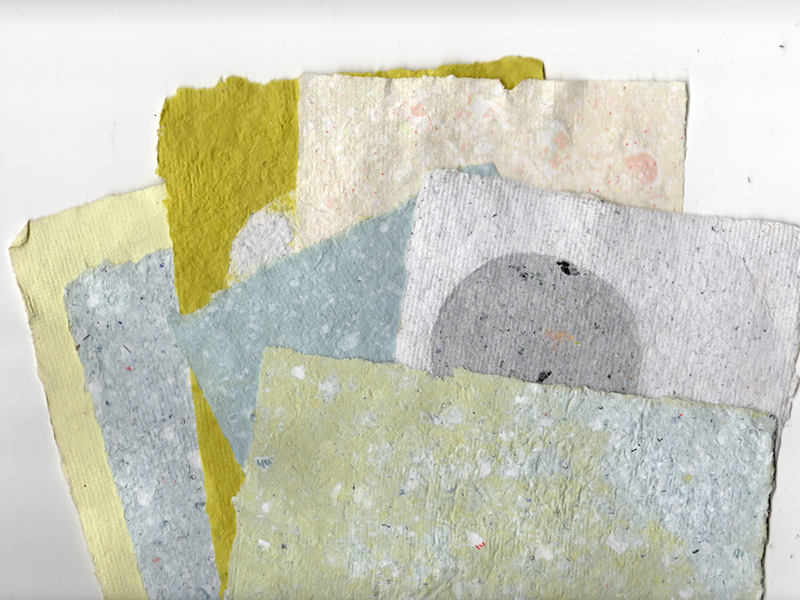

The first and possibly most important issue is the 'conversation' that it is possible to have with both the various processes involved and the materials that go into the making of a sheet of paper. Now that I am more aware of animism as an approach to making connections with the world, I'm finding it much easier to let my mind drift into the lives of things that are not human. As to the material nature of paper, the 'ur-history' of cotton rags could also include the previous lives of cotton clothing wearers, as well as rag pickers, whilst some papers may have embedded into their histories stories of mass tree planting for re-forestation. Hand made papers might include vegetable materials available locally, therefore the lives of local plants might be woven into the story. I went to an interesting exhibition in Leeds over the weekend by Invisible Flock, 'This is a Forest'; an exhibition that tells the story of the artists’ journey across sites in Leeds in an attempt to reclaim a part of the city as a forest. I could easily see how paper making could have become much more embedded into the project they were developing, especially if paper had been collected from the various sites explored and then pulped and mixed with plant fibres also available from plants now growing on the sites. There was a handout available made of handmade paper, that used sawdust made from a tree that had died in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, something that perhaps triggered my thoughts for today's ramble, but I wanted the paper making to be more conceptually embedded into the process. However that was my own 'this is what I would do' response, and it was great to see a big space devoted to a serious attempt to get an idea across in a visual art form. In fact Leeds has been lucky lately and we have had some excellent visual art to experience, such as 'And She Built a Crooked House' by Gemma Anderson-Tempini an exhibition that is still on and which fills the rooms of Burton Grange house in Headingley, as well as the opening last weekend of Hibiscus Rising by Yinka Shonibare. I. e. art matters and if you are a student studying art in Leeds this is a great time to get out and visit these exhibitions.

If you are going to make a practical start and want to have some results quite quickly there is a basic set-up.

First of all you will need a mould and deckle. The mould is a frame covered with metal or nylon mesh, and the deckle is the frame that sits on top of the mould. This how to do it video suggests that you use two ready made picture frames as a simple and quick way to get these made.

How big your frame is will be vital to how you proceed. If only small you can overlap each sheet as you transfer it and gradually construct much larger sheets.

Your mould and deckle will need to be pushed down into a tub of water with suspended particles of fibre floating in it. But you can get over the need for a deep tub by pouring the paper suspension directly into the mould if you keep it in a large jug. You then need to transfer the wet paper suspension onto a flat absorbent surface, such as a felt mat.

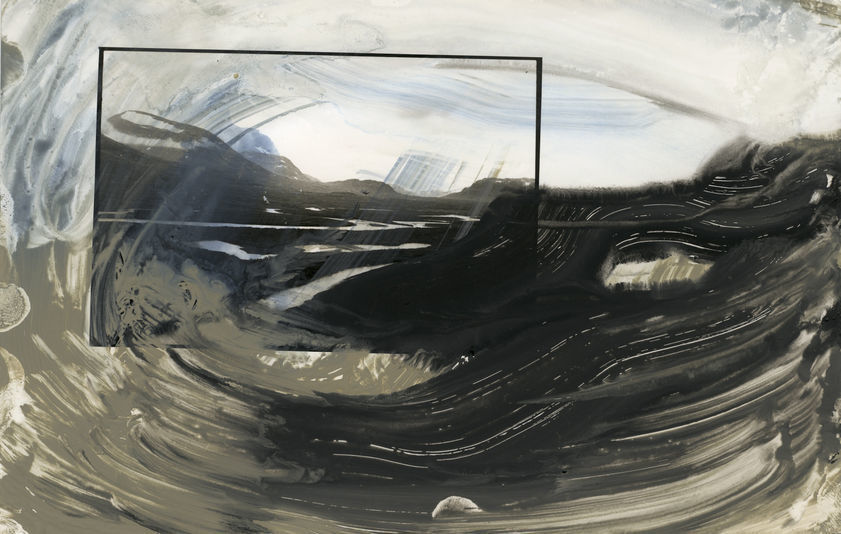

Essentially you are making what is normally thought of as a surface on which to make marks, into a substance that will make your visual communication directly. Either as in Hockney's 'Paper Pools', as a substance that carries the image directly by being 'painted' with, or as a material that can be applied as a new surface on other things, or as in papier-mâché, as a building material.

Paper pulp, soil, wood glue, and mirrors

Step 2: Cover container with an airtight lid and put mixture aside for a week. (If you have a strong good quality blender, at this point you might blend) Add two cups wood glue, and stir until all shreds are soaked in water and glue. The glue will lighten and fluff the mixture.

Step 3: After the mixture sits for a week, it will be time to strain the pulp. Place a sieve over a bowl and pour the paper mixture in.

Step 4: Press on the pulp in the sieve with a spoon to remove excess liquid; discard liquid. Add half a cup of rubbing alcohol to the remaining paper pulp to kill bacteria. The texture should be the consistency of tacky oatmeal.

Step 5: Wearing plastic gloves, take a handful of the mixture and form a ball. Knead and shape it in your hands.

Step 6: Place the ball on a flat surface and sprinkle with coffee grounds, tea leaves or paint pigment on the surface. Compress the ball and add more pigment to stain it further and form a coloured coating. Add more liquid pigment to the mixture for additional colour. It now works like paper clay.

Step 7: Shape the paper clay mixture into a sphere, a sausage or whatever shape you desire and begin to explore its formal possibilities. Some forms will work but others will not.

Step 8: Mould the paper clay over anything you might want to cast, or simply cover, by putting cling film over objects and pressing the paper onto them and then you can link to any other forms you might have made by laying more paper clay around, over and into joint areas and once again pressing tightly to adhere the mixture.

Step 9: Set the forms to dry (ideally outside in the sun), where the colours will change and cracks may form. As you get used to this process you may begin to add reinforcing materials such as muslin.

Paper and sustainability

On line books on paper

Research into paper

More thoughts about paper

Paper sizesPaper: Folding and the songs of trees