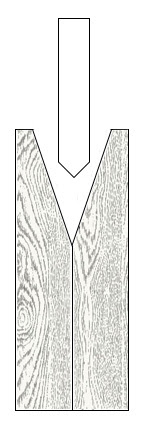

A while ago I posted on the tear and its implications, the split is very similar in terms of visual language but there are subtle differences. I first came across the split as an idea in the work of Gordon Matta-Clark. He had made a series of works he called “cuttings,” in which he opened up buildings by slicing shapes into their walls and floors. In Splitting (1974), he bisected a building and laid it open. The building used, like Rachael Whiteread's 'House', was about to be demolished and he took a slice from the centre of it, undermined its foundations and removed the four corners of the eaves. His approach was methodical and deliberate, it feels as if the house has been cut by a huge knife into two parts.

Creation is itself often understood as a type of splitting. According to the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation epic, the Goddess Tiamat was destroyed in battle by the god Marduk, who then split her body in half “like a dried fish.” He placed one part above to become the heavens, the other half below to become the earth. Marduk used tremendous power to pull apart the Goddesses body, not that dissimilar perhaps to the energy released when we split an atom, an energy release that reminds us of the initial 'Big Bang', an event that supposedly initiated the creation of everything. But humans are mainly focused on another form of creation, one that relies on close coupling and because of this another set of creation myths were born, ones that also rely on the idea of the split. In Greek myth, one day Hermaphrodite the beautiful son of Hermes and Aphrodite, bathed in the lake of Carie, the watery home of the naiad Salmacis. Salmacis is inflamed by his beauty and takes advantage of his bathing in her spring, dragging him down to the bottom of the water, and vowing to never release him. She then prays to the gods not to separate them and mystical powers are used to fuse their bodies together into one that is now both man and woman. This is a tale told most vividly in Ovid's poetic epic, The Metamorphoses. Hermaphrodite, after the for him traumatic event, demanding his parents signify what had happened by making sure all others entering the lake of Carie in future will, as he puts it, 'lose half their sex'.

“Deities whose name I bear, you authors of my days, grant me the grace I implore! that all who come after me to bathe in these waters may lose half their sex!” (Metamorphoses IV, 310)

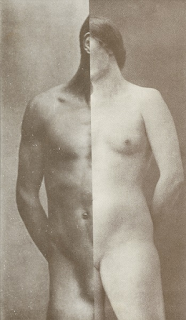

Plato in the Symposium reminds us of an even older Greek myth based on an idea of splitting, humans were he states, 'originally created with four arms, four legs and a head with two faces. Fearing their power, Zeus split them into two separate parts, condemning them to spend their lives in search of their other halves'. This description fits the 1550 image of androgyny below.

Northern School, ca. 1550 Androgyny

The painting above by an anonymous 16th century artist from Northern Europe, can be linked to certain old Bible commentaries. Samuel ben Nahman was a rabbi who lived in the land that is now Israel during the 3rd century. Ben Nahman was renowned for his commentaries on what Christians now call the Old Testament but which are in fact a slightly different collection of Jewish texts called the Tanakh. This is what he had to say about the creation of humans. “When the Holy One, blessed be He, created the first Adam, He created him with two faces, then split him and made him two backs – a back for each side.” (Genesis Rabbah 8:1) The Northern School image could well be an illustration of this "primal androgyne". A similar description can be found in Leviticus Rabbah 14:1 where it is stated: “When man was created, he was created with two body-fronts, and He [God] sawed him in two, so that two backs resulted, one back for the male and another for the female.”

The myth of the primal androgen was well-known in Jewish and Christian Platonic circles in the Middle Ages. This is explained in the book 'Carnal Israel' by Daniel Boyarin, a book that rethinks the unequal distribution of power that characterised relations between the sexes in most post-Christian societies. Boyarin argues that the male construction and treatment of women in rabbinic Judaism did not rest on a loathing of the female body, as has often been previously stated. Without ignoring accounts of sexual domination that can be found in Talmudic texts, Boyarin insists that the rabbinic account of human sexuality, is very different to that of Hellenistic Judaism and Pauline Christianity and he offers possible alternative readings, ones that are derived from ben Nahman's description of the splitting of Adam into two, whereby the two halves are not only equal in value, but that they are always seeking to recombine as a new whole.

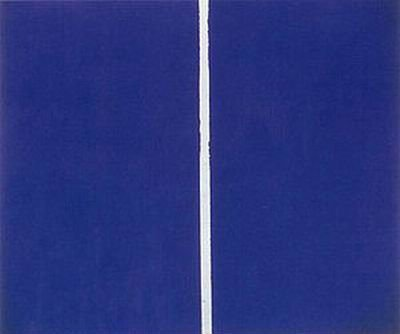

The split as an idea, is often accompanied by the opposite idea of a possible fusion between differences. For instance in the Jasper Johns 'Painting with two balls', two real balls prise his painting apart, but it is visually fused together by his handling of the paint in such a way that the image can be read as a coherent whole.

See also:

The Tear: a line of disjuncture

The zig-zag More on cracks in the fabric of reality

Where stains and traces meet The wound as art

On not knowing and paying attention: Tim Ingold: Differences between intention and attention

No comments:

Post a Comment