Britain's first atomic bomb: The Blue Danube

Sometimes an externalised thought reveals itself as just that, a thought structured by being embedded in things that sit outside of yourself. So how does it work? In order to show how a complex series of associations are constructed I'm going to follow an entangled thought and see where it connects. This blog is about drawing and so I shall start with one.

In the UK during the cold war period of the 1950s someone, somewhere began drawing visualisations of what was code-named 'The Blue Danube'. These drawings were for Britain's first atomic bomb and as the bomb had to be carried inside a casing, the look of the bomb was decided upon by the casing's design. In the 1950s the allure of space travel captured the imagination of what was called at the time, the developed world. In particular popular science fiction magazines vied with each other in the depiction of what things would be like in the future.

Streamlining and smooth curves were often a sign of futurity

So did 1950s designs for spaceships

A typical 1950s space rocket

V2 Rocket bomb

But I suspect it was the fictional form that was the driving force behind the fact that even cars developed fins in the 1950s, and that therefore the underlying visual template for the final shape of the Blue Danube was as much a fantasy as an aerodynamic necessity.

The drawing of the Blue Danube bomb represents a perfect fusion between drawing as a objective plan or idea and drawing as an emotive focus. It is a 20th century technical drawing that I think could be used as a focus for a political concept in a similar way to how the Diagram of the 'Brookes' slave ship was used in the 18th century. The 18th century plan drawing helped galvanise the abolition of slavery movement and I wonder whether or not the Blue Danube image might have enough emotive and conceptual traction to re-energise the long running campaign for nuclear disarmament. As part of the process of adding context, I have converted the original Blue Danube technical drawing into a blueprint. In the book 'A Canticle for Liebowitz' by Walter M. Miller, a post nuclear war Earth is envisioned, whereby after many years Earth is slowly recovering and science is being rediscovered. This process is secretly nourished by cloistered monks dedicated to the study and preservation of knowledge and rediscovered blueprints have now become religious documents and are preserved and copied as if they were relics associated with the scientist saints of long ago. The book reminds us of how science is a force that can be put to use for both good and evil intent and that human beings are actually superstitious creatures rather than the logical thinkers that they believe they are. Perhaps the bomb's blueprint can be used to remind us that we are not the best creatures to handle the dangerous products that can emerge from scientific advances.

Technical drawings help us to visualise possibilities, a process that was called during the Renaissance 'disegno'; an old term, one that describes practices that use drawing as a problem solving or planning tool. However, a technical drawing can also be an emotive image. I am fascinated by the various patent offices' large collections of drawn ideas, many of which never made it into production, but many of which did. There are in the USA certain things that you can't patent, indeed 42 U.S. Code § 2181 entitled 'Inventions relating to atomic weapons, and filing of reports'; states, 'No patent shall hereafter be granted for any invention or discovery which is useful solely in the utilisation of special nuclear material or atomic energy in an atomic weapon'. In the UK we are less strategic, our patent definition states that once you write out your concept or draw a diagram, then copyright should automatically be able to protect your idea. I.e. in the UK an idea is not patentable, but as soon as you write it down or make a drawing of it, it becomes more 'real' and is therefore in a form that can be patented. The technical drawing of the Blue Danube is like all drawings a materially or physically visualised thought, an idea that can therefore be shared with others. There had been a related patent taken out 20 years beforehand. On September 12, 1932, within seven months of the discovery of the neutron, and more than six years before the discovery of fission, the then living in Britain, self exiled Hungarian, Leo Szilard conceived of the possibility of a controlled release of atomic power through a multiplying neutron chain reaction, and he also realised that if such a reaction could be found, then a bomb could be built using it. On July 4, 1934 Szilard filed a UK patent and in his application, Szilard described not only the basic concept of using neutron induced chain reactions to create explosions, but also the key concept of the critical mass. The patent was awarded to him, making Leo Szilard the legally recognised inventor of the atomic bomb. However just because something is patented doesn't mean it will work.

Helene Adelaide Shelby: Apparatus for obtaining criminal confessions

Helene Adelaide Shelby's diagram is also for an accepted and registered patent. The idea was to have criminals interrogated by a skeleton that had glowing red eyes and a spectral voice, its operator being hidden behind a wall. Frightening yes, but not as frightening as the ideas associated with the Blue Danube atomic bomb. The one idea was never realised and the other never used. However some ideas have become realities and they are sometimes twinned with ideas that are fictions.

Prior to conceiving the nuclear chain reaction, in 1932 Szilard had read H. G. Wells' 'The World Set Free', a book describing explosives which Wells termed "atomic bombs". Szilard wrote in his memoirs that the book had made "a very great impression on me." When Szilard assigned his patent to the Admiralty to keep the news from reaching the notice of the wider scientific community, he wrote, "Knowing what this [a chain reaction] would mean—and I knew it because I had read H. G. Wells—I did not want this patent to become public." Wells was certainly prescient, as he put it, ... 'it seems now that nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the earlier twentieth century than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible. And as certainly they did not see it. They did not see it until the atomic bombs burst in their fumbling hands [...] All through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the amount of energy that men were able to command was continually increasing. Applied to warfare that meant that the power to inflict a blow, the power to destroy, was continually increasing [...]There was no increase whatever in the ability to escape [...]Destruction was becoming so facile that any little body of malcontents could use it [...]Before the last war began it was a matter of common knowledge that a man could carry about in a handbag an amount of latent energy sufficient to wreck half a city.'

In Wells' book, eventually after disastrous wars the world is brought to its knees and its senses, and humanity creates a Utopian order, similar to a socialist state. Atomic energy solves the problem of work and in the new order "the majority of the population consists of artists."

The designers of The Blue Danube I'm sure had in the back of their minds 1950s images of streamlined future rockets, and memories of the V2. As you can see in the photograph of the atom bomb below, its more rounded contour is more like the rocket ships as envisioned in science fiction magazines than the more narrow V2. No doubt before finalising the shape models would have been made.

The Blue Danube

As a boy I also had a model bomb to play with, one that I could put explosive caps into and which was weighted by having metal parts inserted into the front section, which meant it always fell point first.

You inserted an explosive cap into the space beneath the metal plunger by unscrewing the top section, which held in place the plunger and a spring. The spring pushed the bottom of the plunger down onto the cap and when the thrown rocket hit the floor, the impact drove the plunger further down into the explosive cap and 'BANG!'. I wonder how many of the Blue Danube designers had children that played with those then ubiquitous toys? Training for the future begins at an early age; training to be a boy included various ways of becoming familiarised with weaponry. Thankfully the Blue Danube was never used in anger; unlike 'The Fat Man' which had been detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki or 'The Little Boy' which was detonated over Hiroshima. Such innocuous names for terrifying killing machines. In the 1950s the sound of the 'bang/crack' of a cap, was either coming from a toy bomb or a toy gun and neither was seen as an issue. I can still remember the smell of sulphur that remained after the caps had exploded, either emanating from the explosive chemicals or from the smiling Devil that was watching the future being constructed.

The Blue Danube waltz was originally written as a choral work. Strauss was commissioned to write a piece for the Vienna Men's Choral Society to uplift the people of Vienna who were feeling disconsolate after losing the Austro-Prussian War. This was a war that saw the rise of Prussia as a military force and the focusing of associated ambitions of a Prussian leadership under which the unification of Germany would result. One it would seem very insignificant consequence of the Kingdom of Prussia's military advances, was therefore a musical composition designed to raise a people's spirits after they had lost a war, a composition that would however eventually give the name to a bomb designed to destroy an enemy based in Eastern Europe, an enemy that had been forged in the heat of battles that had finally resulted in the idea of German expansionism being buried beneath the rubble of two world war defeats.

In the 1960s, 100 years after its composition, the Blue Danube waltz was used as the soundtrack to the docking sequence in Stanley Kubrick's science fiction film '2001: A Space Odyssey'. By releasing the music from its original context, Kubrick opens out a much more cosmic understanding of the music's underlying intent. The Blue Danube bomb was decommissioned in early 1962, just before the Cuban Missile Crisis. A crisis that was a direct and dangerous confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union; the moment when the two superpowers came closest to nuclear conflict. It was a traumatic event I remember very clearly, at one point sitting with my father watching the news and waiting to see whether or not the conflict would escalate into a full blown war and if it did, both of us were convinced that within days our civilisation would be blown away. You cant hide in an air raid shelter from a nuclear attack. This was a situation that Stanley Kubrick would in 1964 recreate as the darkly tragic film comedy Doctor Strangelove. Four years later, it was as if the world had moved on, Kubrick's 1968 vision of a space station took us back to the Germanic origins of the word waltz, a derivative of the German 'walzen', to revolve. In space there is no sound because it can't travel through a vacuum, but a film is first and foremost an idea and ideas can have sound, so if a space station is revolving what else would it 'dance' to, but a waltz? Kubrick was a very astute sound / vision mixer, often using a disjuncture between sound and vision to create effect, as in his use at the end of Doctor Strangelove of Vera Lynn's plaintive second world war associated ballad 'We'll meet again'. We would in the terrifying science fiction Alien films of the 1970s be again reminded, "In Space, No One Can Hear You Scream." Perhaps in the near future it will be the story of Hal, the spaceship's rogue computer that signals the most salient warning within this post, a reminder about a reliance on technology to make decisions for us, especially if we have no control over it.

From Stanley Kubrick: 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In the final scene of Doctor Strangelove, Air Force Maj. T. J. "King" Kong, rides a nuclear bomb as it falls from a plane, as the beginning of mutually assured destruction unfolds, and we glimpse from far above a land due to face imminent atomic destruction. At the time the film was made much of Central and Southeastern Europe was part of the Soviet block, which would have been the land glimpsed below the raving mad King Kong as he rode the bomb to his and everyone else's atomic doom. Central Europe was also the geographical area that the Danube, in all its many colours, flowed through; carrying water all the way from the Black Forest to the Black Sea. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for 2,850 km, passing through or bordering Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova and Ukraine, most of which were at one time part of the USSR, and understood as lands behind the Iron Curtain, a territory that as we now know, is still in some Russian minds, seen as part of a once and still glorious Russian Empire.

The path of the Danube

We are again threatened by the possibility of nuclear war. Vladimir Putin recently delivering a warning to the West over its support for Ukraine, by suspending a landmark nuclear arms control treaty, announcing that new strategic systems had been put on combat duty, and threatening to resume nuclear tests. A consequence in my own more domestic world being that for the past year we have been housing Ukrainians, offering respite to refugees from a conflict few would have believed possible just two years ago.

Elon Musk's rocket ship

The Japanese film 'King Kong versus Godzilla' was also released in 1962, Godzilla being a mythic creature that seemed to have evolved out of the post nuclear aftermath of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bomb attacks. The franchise has been revisited as recently as 2021, the film 'Godzilla vs. Kong' now advertised as a place where 'Legends collide'. The fictional characters King Kong and Godzilla, now achieving a historical gravitas that feels as truthful as any archaeological 'reality'; the myths of Egypt or Greece having a similar status in our collective imaginations as these more recently invented monsters.

The old bomb store that used to house the Blue Danube bomb had at some time been bought by a farmer and converted into a mushroom farm, but he has more recently realised its historical importance and the site has been reopened for visitors and a full scale model of the Blue Danube atomic bomb is now in place so that visitors can take selfies. The entertainment industries embracing both mythical and real histories, a nuclear fusion of narratives from reality and fiction, the aesthetics of cinema, the dream factory, now unifying both.

Hopefully readers will see an idea emerging, one that reminds us how easy it is to accept a dangerous situation, and that the longer we live with it, the more it becomes the stuff of myth rather than reality. Ideas reside within the various connections made between things, they are material concepts, in this case ones made of fictional and real rockets, of music and of human stupidity as well as human invention. Finally a reminder that this bringing together of memories and reflections is another sort of drawing, a drawing together of ideas that would be impossible without access to a computer that is plugged into an ever hungry Internet and that needs a mind that has memories that are triggered by association, to 'draw' all these threads together.

'The Fat Man' mushroom cloud over Nagasaki 1945

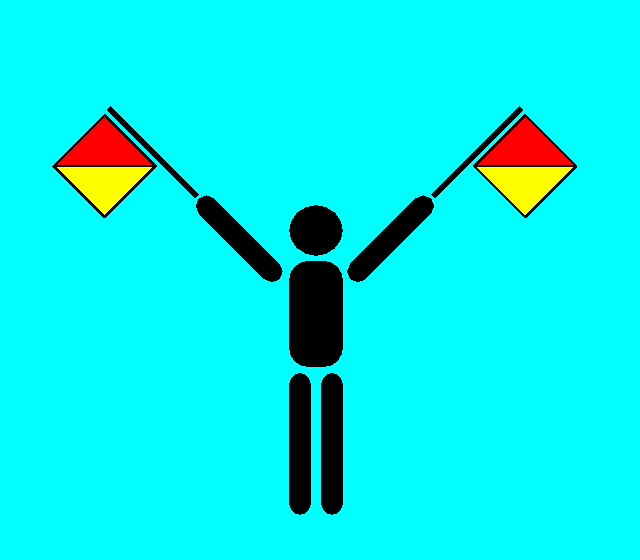

The CND symbol was designed in 1958 by Gerald Holtom, an artist and graduate of the Royal College of Art, who during the Second World War had been a conscientious objector. His symbol incorporated the semaphore letters N(uclear) and D(isarmament). This is how he explained the genesis of his idea; ‘I was in despair. Deep despair. I drew myself: the representative of an individual in despair, with hands palm outstretched outwards and downwards in the manner of Goya’s peasant before the firing squad. I formalised the drawing into a line and put a circle around it’.

Goya: 3rd of May

Goya's peasant is in Holtom's sketch of himself in distress, remembered with arms outstretched downwards. It therefore made sense when the 'ND' semaphore message was embedded into the form of the symbol. If he had remembered the image correctly it would have been a different matter. UD, perhaps 'utter destruction'.

The Semaphore letters N and D

Nothing is straightforward and many groups in the USA in particular but also in the UK, would argue that it is only because we have a nuclear deterrent that we have been able to maintain world peace. The paradox being that in many areas of the world people have never known peace and that conflict continues to re-emerge constantly.

The fact that a B52 bomber is formally similar to the peace symbol allows it to be used to support another idea, the entangled nature of these connections now becoming even more twisted. The clarity of the CND symbol does lend itself to many uses, one of which is to use it as a sort of cross on which to break other symbols, as in the image below.

And so back to the drawing board and the blueprint

The interesting thing about a ramble through a range of connections is that it both demonstrates how interconnected everything is and how an initial thinking process that simply connects one thing to another, eventually leads to an idea, or range of ideas. A performance piece might begin with a group of performers signalling with flags from the top of a particular building, perhaps signalling the details of a non proliferation peace treaty that has recently been broken, or details of people still after all these years affected by nuclear fallout. Other juxtapositions might be found for Strauss' music, Kubrick's films might be revisited for their sculptural potential, blueprints represented as religious icons, toys returned to by yourself as an adult and the implications of revisiting the memes of childhood as a grown up. It was the incongruity of naming that first of all drew me to this series of thoughts, a 19th century waltz becoming the name for a 20th century atomic bomb. This piece of everyday Surrealism reminding me that there is nothing more strange than reality.

Any artwork is of course media specific. In this case the blueprint of a broken bomb embedded into and broken across an image of the CND symbol is a digital one. One media specific nature of digital images is that they are pixilated, and in this case the bomb drawing was developed from a low resolution image capture of an online article about the history of the Blue Danube bomb. Therefore you can never get close enough to read any text, in fact as soon as you increase the size of the image it begins to go out of focus and as you do this the image dissolves into abstract patterns. This aspect of digital screen based images for myself is a deep metaphor, one that relates to the cosmic reality that lies beneath all apparently solid things. If we look closely at matter, the greater the magnification, the stranger it becomes. Eventually in the world of the electron microscope we arrive at what we think of as atoms, by their very name indivisible units, but as we get even closer, we find them dissolved into neutrons, protons and electrons and then as magnification increases we step into the strange world of quarks, mesons, bosons and hadrons and eventually we lose sight of particles of matter altogether and all we find are interconnections of vibrating waves of various energy fields. Electromagnetic, weak and strong nuclear and gravitational fields, appear to vibrate into and out of existence, they form the possibilities for various universes, realities that also exist in dimensions far beyond our very narrow experience of the four dimensions we are used to. The digital screen world as a specific medium is thus a magical one, one that exists as a phantom. Its surface appearance is a constructed ghost, each pixel position a reflection of a code beneath a code, an object-orientated system of code and data intertwined to produce something we treat as a reality but which is in fact a digital dance. As I walk through my adopted home city of Leeds, everywhere I look I see people gazing at digital screens, locked into phantom worlds, glued to dance partners that are to them as real as their own flesh and blood. I type these words on another screen, I am also partnered with an inanimate but animate object, living with a new religion that is a reconstruction of the very old one of animism. Just as I embed this object with a thought, my ancestors communed with plants, other animals and the landscapes they inhabited. For thousands of years they believed in the dreamtime of a beginning that never ended, holding, as the aboriginal peoples of Australia still do, a belief that the Dreamtime is a continuum of past, present and future. The idea of the atom bomb is an idea predicated upon a particular understanding of how matter and energy are woven together. Their forceful separation is a type of transformation, matter transforming into energy and as it does it unleashes a nuclear force that transforms all realities within its immediate vicinity; mimicking a moment from the beginning of time, the moment of a vibration's first fluctuation, a gravitational wave that still waves to us from a past, that is also our present and our future.

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment