Van Gogh: Olive trees

Cezanne: Pine trees

Adolphe Appian: A Great Beech Tree

Pine Trees: Hasegawa Tohaku

Thomas Gainsborough: Trees in landscape

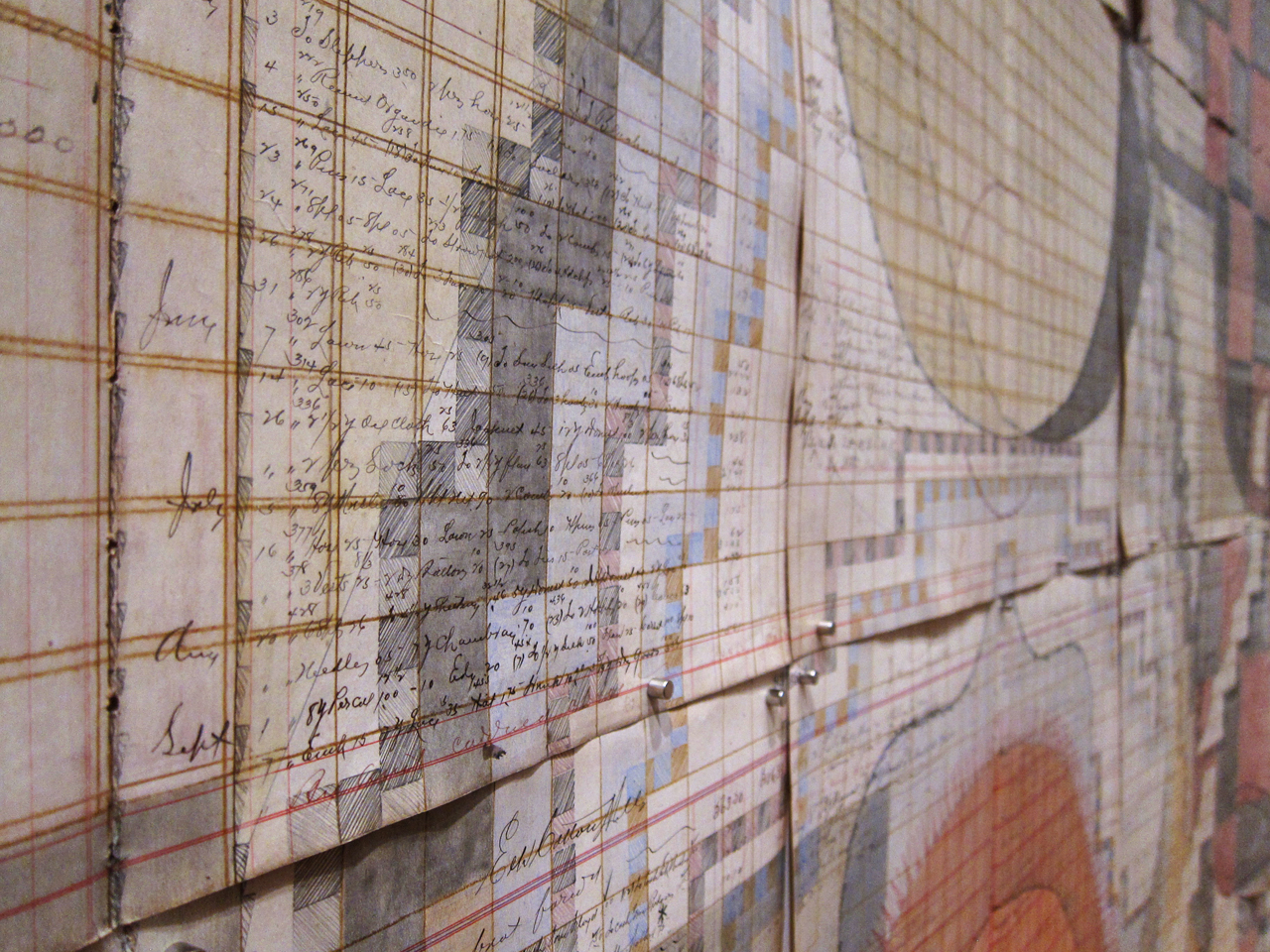

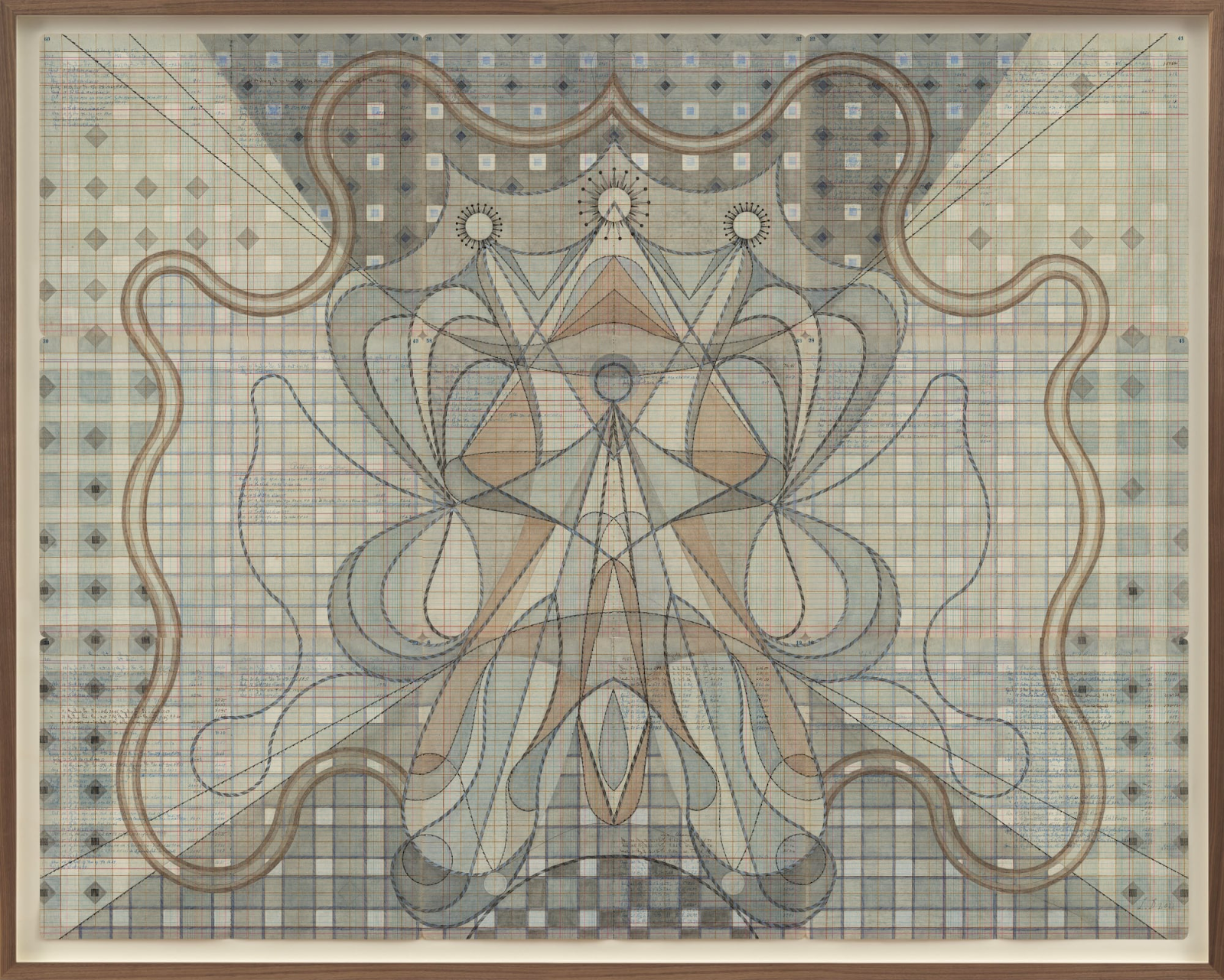

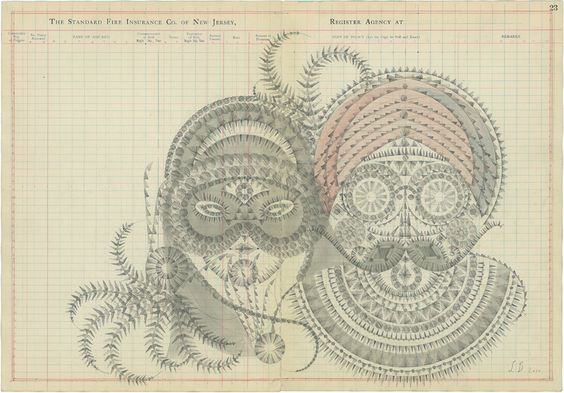

Artistic sensibility is a strange thing, it is something seen but not heard much of. If you make an image of a tree and I make one as well, when we put them side by side they will look very different and the thing that will define that difference will be sensibility. Your sensibility is different to mine. It is sometimes called style, but style is something worked on, something refined, something looked for as a type of individual signature, but sensibility is just how it is. You cannot escape your own sensibility, it is a true reflection of you and lies deep within the structure of your images as well as deep within yourself. It has however also been defined as 'the sensitivity and capacity to appreciate and act upon concerns of or pertaining to art and its production' (Ingman, 2022) It is in this case not just about what is inherent to myself, but something about my sensitivity to the broader concerns of art itself. Sensibility is an inherent characteristic of any artist's work and approaches to representation are rooted in the formal aesthetic consequences of these differences in sensibility. The images of trees that grace the top half of this post being my attempt to illustrate this issue without the need for words.

The representation of the world using hand made images is embedded into aesthetic considerations, the forms that we draw are not only attributes of how we make them; they are part of the process through which these things are made. The type of marks I use to make a drawing are an extension of my sensibility, my 'touch' being a combination of the physical and mental control that I both consciously and unconsciously exert within my making. Through experience I know how for myself forms will look and function within a finished drawing, which is a necessary understanding on my part, if I am to put my 'stamp' on those particular aesthetic qualities that are part and parcel of what I would call 'my work'. Such knowing requires me to be an active and intelligent maker and is a sign by which I recognise other active and intelligent makers.

Sketchbook image of a Tree: 1980

Sketchbook image of a tree: 2022

As I get older I'm also very aware that sensibility changes and I can now show my own sensibility changes to myself by going back to old sketchbooks and looking at what I was drawing 40 years ago. In many ways I remain the same but I can see in recent drawings less preoccupation with image and more interest in rhythmic variation. I am of course changing physically as well as mentally and my fingers no longer move as freely as they did, but this is compensated for by the fact that my mind/body is more capable of recognising what it is that I think I'm doing.

Sensibility is often associated with romanticism and individuality. The artist's unique handling of their materials was at one time regarded as an essential aspect of art appreciation; when I was a student, part of our art history training was focused on the ability to recognise artists from small details or sections of their work. You were supposed to recognise the difference between let's say a Murillo and a Raphael by looking at the way a coat sleeve and hand or a section of background landscape was handled. You were being trained in a type of connoisseurship, whereby your 'taste' was seen to be refined because you could spot the difference between 'real' and 'fake' artworks, as well as between famous and not so famous artists. This approach is of course still important to those that work for the big auction houses such as Christies or Sothebys. In French there is the term, 'la patte' which is sometimes used to refer to the artist's 'mark'. In all of these uses there is presumed to be a value in difference. The artist's signature style is often seen as a mark of genius.

This is how people on the edge of the art market view the issue:

'A signature art style reinforces brand recognition and will help your artwork grow traction. You know you’ve nailed this when customers glance at a new piece in your portfolio and instantly recognise it as yours.'

'Your signature style is the most important factor that sets you apart from everyone else and will make your work recognisable.'

Ok, so what does this mean? For the art market difference and uniqueness are more valuable than profundity of expression, raising awareness, seeing the world differently or even making a better piece of art. If you want your prices to go up, you need to produce work that has a unique sensibility or rarity value. The capitalist system in effect is defining your work, not as part of an ideas communication system, or as a spiritual encounter but as part of a commodity exchange system. The media is far more concerned to discuss what a painting is worth, than to discuss what it might mean and there is a desire to invest in something that is 'authentic'. (Of undisputed origin and not a copy; genuine) If we look at the art of ancient Egypt on the other hand, the same style was maintained for thousands of years, and each artist was taught to copy the forms that were laid down by the ruling powers.

But what if sensibility had more to do with structure. What if it operated as the bricks with which you build your house? During the 18th century it was often argued that individuals who had ultra-sensitive nerves would have keener senses, and be more aware of beauty and moral truth. However a refined sensibility it was believed, also led to a physical and emotional fragility. This combination meant that people with heightened sensibility were on the one hand seen as possessing a type of illness that was at the time called "The English Malady," (hysteria" or "hypochondria), but on the other hand certain people who were also 'sensitives' were seen as having an artistic sensibility; a virtue that allowed them to see things that others could not. This situation still exists in popular culture, the effeminate, unpractical artist, is still a trope within certain parts of society, as is the genius artist, whose refined sensitivity gives to the work of that artist a particular look that is unique. But if this heightened sensibility led to something else, such as a recognition of how ideas and concepts could be built from the sensitive engagement between the artist and a material; then a more positive and robustly creative definition of sensibility could be arrived at. If we go back to the images of trees at the start of this post, then perhaps we can tease out another, alternative meaning of 'sensibility'.

Van Gogh's 'olive trees' is an image composed of dynamic energy flows. The characteristic dots and dashes that he uses to compose his image, are his building blocks, the bricks and mortar with which he builds his world. A short stab alongside a jab, a twist alongside a tick, a rhythmic tic tock of hand jive, are all woven together to create a patchwork of flowing, rhythmic marks, that is unmistakably Van Gogh's. He 'lives' within these frozen gestures; gestures which capture his speeding fingers thinking their way across the paper surface. This is sensibility as structure, this is not about the too sensitive artist, this is about a sensibility that can build concepts, that has a muscular structure enabling it to wrestle an image into shape. We can argue the same thing about Cezanne who has also managed to form a conceptual vision out of his fleeting visual perception of a particular stand of trees somewhere in southern France. Again the building blocks are small units of mark making, units that build up to form a new unity. In Cezanne's case they are inextricably linked to his concept of 'petite sensations' his awareness of the process of looking and how this process had to be recreated as images.

Kubo Shunman was a Japanese artist renowned for his delicate sensitivity and avoidance of harsh contrasting colours. Like Van Gogh his marks build the surface structures that control our vision, however his touch is smoother and more flowing than the European artist and if you look at the accompanying calligraphy, you will see where his particular style of application comes from. This is drawing that has evolved out of calligraphic writing, a practiced hand underpins each mark and a deep appreciation of the potential symbolic nature of forms surrounds and integrates both the calligraphy and the drawing. Adolphe Appian is an artist of the outdoors; you feel the wind whistling through ink marks which he uses to establish the main tonal elements of this drawing. He then uses looping contour drawing of black chalk to pick out the tree's weight and solidity. The brush gives him expressive movement, the chalk volume and weight. He makes dashed lines to indicate foreground grasses, pushing one type of mark against another, an indication of a complex sensitivity to a wide range of material possibilities when making an image. It is as if his mind/hand flicks between an awareness of the tree's inner coiled strength and a flowing world of flickering leaves and wind blown grasses.

Hasegawa Tohaku's drawing has a minimal, reserved aesthetic, that is able to use the empty voids within the image to carry the weight of his sensibility. His building blocks are of spaces as much as they are of marks. He draws the world's emergence from a cloud, on those days when the mist covers everything and only gradually can forms begin to be picked out. Atmosphere becomes concept, touch hardly there, just enough to make you feel the cloud. Finally, Gainsborough has a flowing touch, one that skims over the surface. You feel the direction of his diagonal hand movements, as the image evolves under his fast fingers. A lightness graces his drawing, allowing sunlight and vegetation to flow alongside a breeze that moves through the scene. In this drawing nothing is fixed.

You would not mistake these artists for each other, each one has evolved an approach to drawing that allows them to give an overall control to the feeling tone of their images. This control is what I'm pointing to as 'structure'. Just as when you scan a building made out of brick rather than stone, you quickly sense the difference in overall shape between the brick structure and the stone structure. Bricks allow one type of shape to form, stones another and so it is with the individual marks that are the result of an artist's particular handling of a drawing material. This is not to do with any particular sign of genius, just as a deer moving through a muddy field will leave particular hoof prints that depend on its weight, sex, age, build and state of mind, (is it running from something, browsing for food, looking after a young fawn, investigating new territory etc.) an artist leaves traces of their actions dependent upon weight, sex, age, build and state of mind. Intentionality is of course the measure of difference here, how much of a difference in intention lies behind the marks I make and the marks the deer makes? In my world of course I am inclined to think that my marks exhibit more intention than a deer's, but in the deer's world perhaps the forms of marks in the mud mean far more than I can imagine.

Reference

Ingman, B. C. (2022). Artistic Sensibility is Inherent to Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21.

See also: