I am on my way back from a conference in Porto, entitled "Drawing Across Along Between University Borders". It was designed to bring together drawing professionals responsible for the future of drawing as an academic discipline and was held over three days, 16th to 18th of October.

I haven't been to a drawing conference for a while, but I had been to Porto before, as it was the venue for my last week of work for the Leeds Arts University before I retired, or at least thought I had retired. I had previously delivered a workshop that was designed to last for a day, looking at how people from any discipline could begin the process of visualising feelings, whether these were emotional or physical, such as a particular pain. This time I was back in Porto to deliver something similar, but in a much shorter timeframe, I had just one hour to communicate my idea and to add on to it a further concept, the idea that an embodied visual language could be used to illustrate intellectual ideas as well as embodied feelings and that the two were intimately related.

Conferences are always structured in such a way that you have to make choices as to what talks and workshops you will attend, therefore any one person's view or experience is shaped by the path they take through each day. My reflection on what I experienced will therefore be very personal and coupled with the fact that I am prone to be interested in some things more than others, my reflections are therefore totally biased, but hopefully they might give a reader a sense of what was driving the conference's agenda, and offer a glimpse of my own personal agenda for wanting to attend it.

Throughout the conference there was the reassuring presence, thoughtful remarks and background support of Paulo Luís Almeida and without his energy and commitment to the project it would have been a far less rich and enlightening event and he was always there to introduce the various hosts and speakers, including of course opening remarks.

Day one

There was an opening performance, whereby Silvia Simões, the drawer, and Lucas Oliveira, the saxophonist, responded to each other, or perhaps the drawer mainly responded to the saxophonist, I wasn't sure. A live feed using a camera directly overhead of the paper on which a drawing was orchestrated, was projected on a screen that was central to the stage on which both performers operated. The saxophonist to the left and the drawer on the right.

Silvia had taped graphite sticks to her fingers and thumbs, so that they operated as extended nails and as the saxophonist changed pitch or rhythm, she responded by making marks on the white paper sheet set out horizontally on the table in front of her. Beginning close to her body, as louder marks were made her hands moved into the spaces further away from her body. Gradually as the event continued, certain marks would begin to indicate particular types of repeated rhythms, marks clustering together to form energy patterns. However the light reflected off the paper into the camera lens was uneven, and the marks at the top of the drawing disappeared into the light's reflection and I began to wonder if this was on purpose or not. If it was on purpose, its use it seems to me was to remind us all of the media specificity we were experiencing, which was as much about the video camera, screen and lighting, as it was the two participants, saxophone and drawing materials. If it was an accident due to a failure to test the lighting beforehand, then like all accidents, perhaps it could be worked with as an integral aspect of the next performance. This issue was something that for myself set out a sort of question that would begin to open out as the event unfolded, how much learning was I going to get from the conference that was orchestrated and intended and how much of the experience was going to be embodied via unintended actions and serendipitous events?

In this case I was reminded of one of the moments I was planning for my own workshop, which was a brief introduction to sound and shape interrelationship, the kiki / bouba effect and I immediately began questioning how well that was being illustrated by the performance.

The first workshop

The first workshop I attended was under the umbrella of 'Hybrid knowing spaces, between art and science'. Maria Manuela Lopes introduced us to issues surrounding 'Drawing the Genome'. I think there are about 3 billion DNA letters in the human genome and they are combinations of four letters adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). The order of these chemical bases, or nucleotides, in effect defines our genes and encodes all the information needed for our cells to function. I was given a single sheet of code, one of the many that would be needed to be printed off if the full sequence was to be made available. It was a daunting task, not only to imagine 3 billion letters in various combinations, but to even think that in a short period of time an artist like myself could contribute anything to the problem of awareness of the complexities involved. But this is what we were asked to do. I simply scanned the page and let my intuition decide on three short sequences, two that I scanned horizontally and a third that took my attention as a vertical line, which I sort of realised went against the grain of reason but as these actions were totally intuitive, I thought why not go with the flow. I picked four different colours to represent the four letters and simply reproduced the lines of code as coloured dots. I then thought about the 'resonance of clustering'. By this I decided that one letter on its own would have a certain 'energy'. Two together would have more. I don't know why but it felt right, and so I then redrew the lines of code changing the spacing between the dots depending on my intuited energy changes. All of this was totally illogical but it made me aware that no matter how difficult or incomprehensible our experiences are, we will always attempt to interpret them and that this was perhaps what Maria was trying to extract from the session, not an answer to the problem of how to use visualisation techniques to explain the genome sequence but to explore how a group of visual professionals would respond to a seemingly impossible task.

The Keynote session

The keynote session was delivered by Shaaron Ainsworth: Drawing to learn, teach and assess in science.

Shaaron was asking us to consider what learners do when they draw, and how does new knowledge emerge when learners draw? Drawing was defined by her as the construction by a learner of a static visuospatial representation, that is intended to be meaningful. (This was of course in my mind questionable, especially as I have in my last two years of teaching been focused on working with sequential narrative and animation students). The lecture was though about how the learning and teaching of drawing in relation to the sciences was operating, so I tried to hold back my questions. Shaaron explained how drawing sat within a culture that embraced representations that were shaped by cognitive processes that were both social and metacognitive and interestingly for myself 'expression' was in a way boxed off from this. Her explanation led her to make another statement that I found questionable that these visual expositions were, "intolerant of ambiguity". She went on to state that these drawings required 'ontological commitment". As an illustration we were given a knife and fork to think about. An image of these two things would have to be either one thing or another.

For instance, in the image above the fork is on the left and the knife on the right, this particular fork has four prongs and the sharp edge of the knife sits adjacent to the fork, rather than being turned away from it. I could understand this and could see that when a drawing was completed it became a definite statement. But when drawing also tries to illustrate an additional element, such as time, things are often ambiguous, such as the drawing below, which is an attempt to represent not just a knife and fork, but the fact that at different times they might be placed in different relationships.

I'm afraid my mind is always flitting about and Shaaron was now pointing out how action supports perception. We are always testing things out to see whether or not they are what they appear to be. Memory is supported by the external events that we can locate it into. (Yates: Art of Memory, is the best book I have read to support this) There are modality specific memory systems, i.e. not all memories use the same neurological pathways, these issues lead to a very fluid bidirectional relationship between the mind and the world. This led me to think about the role of drawings and the making of ideas as material things and how they operate as forms of external thinking, allowing us to think, literally 'out of the box' of our minds. I was reminded of Pasztory's thesis that humans create things in order to work out ideas, that we 'think with things'. Her idea was that the art-making impulse is primarily cognitive and only secondarily aesthetic. I must go back and re-read her book, 'Thinking with things'. My flitting about mind perhaps being a good example of what Shaaron was referring to as metacognitive thinking, or the constant evaluation, monitoring and planning that goes on in relation to our constantly ongoing performance of life. These cognitive demands are though very demanding and visual forms such as images reduce cognitive demands, which is on the one hand good, but on the other it means that learners only spend a few seconds actually looking at images. So what can hold their attention? Affect can be linked to emotional impact, this can excite curiosity and heighten awareness of intent. I was here reminded of the work I had been doing working with a graphic novelist on communicating health issues. A young boy was at an exhibition opening with his mother and he came up to me because he wanted a copy of the yet to be published publication, as he was excited by what he had just seen. The publication was using the visual language of the comics he read and he saw that immediately and was drawn to it. I then realised that we had been using the wrong visual language, it was one that would appeal to the boy's age range and perhaps gender too, but not the older men we were looking to communicate with. We had created emotional affect but it was not properly targeted. More focus group testing was needed.

From Doctor Simpo's '"Things and Stuff'

Shaaron now moved on to point out that drawing anxiety was common. I. e. that many people felt that they couldn't draw and that it was an alien way of thinking for them. She then pointed out that reproductions were cultural practices and that they were a product of cumulative culture. By this I thought she meant you need to keep making images over and over again and passing them back and forth between ourselves before they become clear pieces of communication. I was reminded of the work of Cezanne, whereby initially it was seen as clumsy and awkward, but as more and more people were exposed to his continually evolving language, gradually they began to see that he was communicating something unique about how we see the world and that his work wasn't clumsy, it was just that initially it was hard for audiences to read what he was communicating. Drawings are therefore in their reception, part of active, constitutive, interactive events and that this complex combination of mental and physical activity is required, if the new information they carry is to be integrated with and into someone's existing knowledge.

For an example we could think about how we might draw the external features of the human heart prior to dissection. Without the experience of dissection, we would draw the heart poorly, but after the experience, we know which features to clarify in order for someone to understand what is going on. Drawing focuses attention and attention can only be attained via knowledgeable looking.

We were asked to think about constitutive drawing, something that I understood as drawing that establishes or gives organised existence to something. This was an activity that could create visual reproductions that go beyond the information given. For instance drawing diagrams based on written texts. These drawings could be thought of as a type of meta-analysis. The final example was of children drawing an evaporating wet handprint and was used to show how invention was used to show time in action. I thought the marks made were rather like ones used when people try to illustrate a disappearing trick within a magic act. I was wondering whether the children would think of this as magic or science? When observing how wet materials dry when exposed to the air or sunlight, we are watching something invisible happen, and it is for myself, within these moments hereby invisible agents are at work, that drawing can add to our understanding. Drawing can offer something that perhaps purely logical understandings cant; by virtue of its externality, and the fact that it is therefore read as part of the world of perceptual experience, it can capture the fact that all events are perceived by us as much as emotional experiences as logically understood ones.

The keynote was followed by parallel sessions.

I attended the four 'Drawing Across' Creative Reasoning presentations

1. Dean Kenning: Diagramming theory: Diagrammatic drawing as a method of close reading across disciplines.

Dean is part of the diagram research group. I had come across one of his diagrammatic images before, because one of my ex students, Helen Clark, had included his diagrammatic image of Walter Benjamin in a book she joint edited with Sharon Kivland, 'The Lost Diagrams of Walter Benjamin'.

He spoke about using diagrams in workshops and pointed out that 'diagrams exhibit their meaning to the eye'.

The process of taking a complex text and then translating it into a diagram was shown to be an excellent way to get students to grapple with and come to an understanding of the key issues that emerged from dense theoretical texts, something that I was very empathetic with, as for several years I was head of contextual and theoretical studies at Leeds College of Art.

As he talked I remembered seeing Kurt Vonnegut explaining stories on a blackboard, he showed us how to graph the shape of a story by drawing two axes: one representing the story's chronology, and the other representing the protagonist's fortune. He then went on to graphically sum up several fairy tales, an event that must be now from over 40 years ago, but he was so engaging and funny that everything from that session stuck. I'm afraid as I reminisced I spent more time drawing. Not that Dean's presentation was not interesting but that by now I was getting mentally tired and drawing always helps me to refocus.

Drawings from my notebook

Dean was presenting in a lecture theatre, standing behind a lectern, talking to images as they came up on the screen. The audience were therefore behind him and because many of the attendees had gone to the other parallel session there were several empty seats. I began to see the situation spatially and drew a space cube to show how the audience rose up from the stage in steps. I'm afraid I was becoming more interested in the separation between the audience and the presenter than the content of the presentation, wondering whether the situation was communicating more than the lecture. I have since gone on to look at the work of the diagram research group and therefore hopefully have been able to better inform myself of the work Dean was introducing. The book, '

Drawing Analogies: Diagrams in Art, Theory and Practice' by Dean and his fellow researchers is due to be published early next year and I look forward to reading it.

2. Marco d'Alessandro: Lost in the gutters: Creativity studies and creative practices through comic based research.

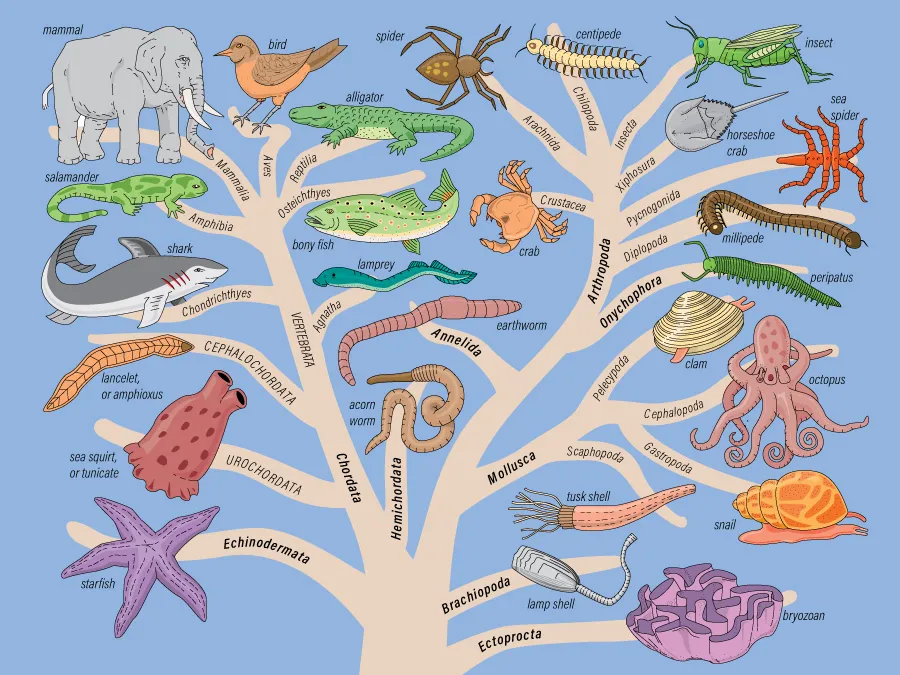

Marco introduced us to the fact that representations have a history. For instance knowledge trees, those branching diagrams that we are all familiar with, have a history related to family tree drawings.

An old family tree

A phylogenetic tree

Marco pointed out that drawing was something that could take us into understanding and that comics inquiry included meaning, perception and experience. He was working at the intersection between comics and the visual language of healthcare. After looking at his work, I was further reminded that I needed to revisit the work I had done with 'Doctor Simpo' at some point and to revisit the illustrative work of Sophie Standing, who produced some excellent drawn images for the '....is really strange' series written by Steve Haines. In particular 'Pain is really strange', is a publication that I thought Marco might explore as the work of a fellow traveller.

Marco's work reminded me of Shaaron's definition of drawing and her inclusion of a 'static' aspect within that definition. The issue about the gutter is that it allows for temporal transitions to occur between frames and in doing so, allows images to open out an unfolding interpretive story. Drawing does not need to be static, and even within one frame, there are multiple possibilities for temporal understandings. For example Richard McGuire's 'Here'.

3. Marta Cruz and Paul Berry: IN OUT ON DRAWING: Interweaving architecture and fine Art

This presentation was centred on various ways to represent architectural space. In particular how to capture the phenomenological aspects of spaces. Perspectives and plans and elevations do not allow us to experience architectural space, they only illustrate it. Therefore they had devised models and ways of working that meant that the tonal experience of light reflected off the surface of objects was brought to the fore of the drawing experience. First of all a box was made with a window cut into its side, so that when objects were placed inside it light would be cast across them from an angle. The three dimensionality of the situation was clarified by this process, but most importantly the experience of light was enhanced. Then the box was re-constructed so that a viewer could look inside from a particular fixed viewpoint. (see the drawing below of someone holding the angle shaped object so that they can look inside) Students were then given various objective drawing exercises using atmospheric tonal values to help them explore the implications of this way of working.

Notes from my notebook on 'Interweaving architecture and Fine Art'

4. Michael Lukaszuk: Interactive drawing as active notation for digital music performance

Michael's work was centred on the translation of drawing into sound. He was interested in research focused on 'sonification', citing Loveless's definition of 'a boundary object' taken I presumed from her book, 'How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation'. Loveless introduces us to the idea of art practices as research methods in their own right and I presumed that Michael was trying to reassure us that his practice was just that. As an example of this we were introduced to 'TIMEPIECE FOR A SOLO PERFORMER' by Udo Kasemets, a work from 1964.Udo Kasemets: Graphic score

Michael was then using the rules developed for this previous work's formal language, as a way into his own investigations into sound/visual interaction. For example the higher up on a vertical line a shape may sit, the higher its pitch might be. The interesting issue here was what now emerged from a practice that was using digital technology to re-visit a piece of work made before digital technology was available. He was interested in machine learning, which trains a model on known input and output data to predict future outputs, and we were presented with some examples of the sounds that had been generated as a byproduct of this research. I thought this work felt as if it was in its early stages and that the shape/sound interrelationships were as yet very crude, but the potential is very interesting.

The round table discussion at the end of the day wasn't that insightful and was more to do with possible directions the conference was taking and people were getting thoughtful as to whether or not to go to the evening's reception over at the faculty of fine art. I was by now very tired as I hadn't slept well the night before and had spent like most people several hours travelling the day before, so decided to go back to my hotel to sleep. What was emerging were questions as to the transferability of the types of skills we had been introduced to, in particular what are the drawing tools that we use to think with and if we can identify them, can we put together a tool kit?

No comments:

Post a Comment