Tuesday, 30 June 2020

FAT is dead, long live FAT

Thursday, 25 June 2020

The Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize 2020

I have posted before about the importance of what was formally the Jerwood and which is now the Trinity Buoy Wharf drawing prize. 2020 is the 25th consecutive annual holding of this prize and accompanying exhibition and to celebrate this, the call for entries is going international, and is now open for artists from the UK and around the world. There is another new addition: the Working Drawing Award, which focuses on the role of working drawings in art, architecture, design, engineering, manufacturing, science and if you are a regular reader of this blog you will be very aware of how I have attempted to open out the conceptual framework around which we can think about why drawing matters to include the work done in other disciplines. In particular it would be interesting to look at how even more disciplines could be included, such as police crime scene drawings or those done for archeological digs or circuit diagrams.

The Trinity Buoy Wharf drawing prize has been led by its Director, Professor Anita Taylor, since its inception, and she is passionate about drawing in all its guises. She has helped raise the profile of what has sometimes been a forgotten art form, and she continues to work hard to communicate and support an understanding of drawing as a medium that is central to the way that humans communicate with each other.

The entry date has been extended and it is now going to be the 9th of July. All the details for entry are on the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing prize website and there are regional as well as London drop off and collection points.

See also:

Wednesday, 24 June 2020

The zig-zag

Zig-zag patterns alongside dots and other abstract shapes, can be 'seen' because of the fact that eyes are embedded into your body. We sometimes forget how much a part of the body the eye is, it cant be separated out from the way blood circulates or the nervous system works, but we tend to think of our eyes as being a sort of window through which we perceive the world, rather than a working organ that like all our other organs is integrated into the rest of the body. The eyes operate in such a way that they are also looking at our inner selves at the same time, but we tend to forget that. One of the reasons that we see entoptic images is because of the movement of white blood cells in capillaries in front of the retina. Another reason is that floating coagulations of vitreous jelly can drift through the interior of the eyes and you sometimes see them or if not these 'floaters' themselves, traces of their movement, as your eye attempts to focus on them. The zig-zag you see being your brain's attempt to decode your own eye's movements as it tries to 'see' something. One zig-zag form in particular is called the “Purkinje Tree”, this is when you see your eye's blood vessels when light shines into the pupil from an unexpected angle. Another way to get the brain to 'see' a zig-zag is to apply pressure to your closed eyes and this generates a phosphene, perceived as veiny or zig-zag-like lines. These phenomena only come into vision when you are faced with a plain background such as a white wall or a clear sky. Normally there are too many interesting things going on for the brain to be bothered with these insignificant visual events. “Prisoner’s Cinema”, an effect that occurs when you are in darkness for a long time, is another example. A “light show” in the mind gradually emerges out of the blackness, and often begins with abstract zig-zags and dots. There is a further stage to this effect, as time goes on and there is no relief from the dark, the mind begins to 'see' other more recognisable things and abstract amorphous forms gradually take on animal or human like shapes. This effect it has been theorised, is why cave painters produced both abstract forms and representational ones and most importantly mixed them together.

The Pech Merle cave in France has drawings on it's walls from 25,000 years ago, (the spots are made by a controlled 'spitting' of the pigment mixed with saliva and that is how the hand stencils are made too). Imagine 'seeing' a cloud of dots, and then gradually a horse form emerges from them and then as the horse form takes shape, you are also breathing out spots of paint. Perhaps drawing a line with one hand, whilst spitting paint over the other hand that you are using to steady yourself against the cave wall. One image grows from another, and then as the horse emerges, you begin to 'decorate' its edge by spitting dots to surround it. In many ways our minds are still in that primeval darkness, every time we close our eyes we slip back into our old skull cave.

There is an engraving that was excavated from a riverbank in Indonesia that is so old that it couldn't have been made by the humans we call Homo Sapiens. It is thought to have been drawn by an individual that belonged to the species we now call Homo Erectus. That these creatures were human like was at one point doubted and the fact that they have drawn designs on objects such as shells, in many ways changes our view of what we are and how we relate to everything else. The divide between ourselves and other species is perhaps not as sharp as we thought, and we are not alone in feeling the need to scratch a sign into the world. The fact that the oldest drawing we know of is a zig-zag, also suggests that we ought to pay a little more attention to zig-zags than we usually do.

The video below describes the history and science behind entoptic phenomena, as well as how to produce them yourself.

Entoptic phenomena

Zig-zags can be like cracks. The crack in the floor of Tate modern by Doris Salcedo, entitled 'Shibboleth' refers to the Biblical tribe the Ephraimites, who when attempting to flee their persecutors across the river Jordan were captured by their enemies, the Gileadites. In order to check they were of the Ephraimites tribe, every person was asked to pronounce the word, 'shibboleth'. Their language did not include a 'sh' sound, so if they couldn't say the word, they were executed. A shibboleth is any custom or tradition, usually a choice of phrasing or even a single word, that distinguishes one group of people from another. It is one of those differences that gives people the power to judge, to reject others or to kill them.

For Salcedo, the crack represents a history of racism, running parallel to the history of modernity; of the divide between the rich and poor, northern and southern hemispheres. She invites us to look down into this crack, and to confront discomforting truths about our world, truths that are at the moment coming home to roost.

We are embedded into our world and the concept of an art form that is separate from the culture we inhabit is a very strange one. Kant's aesthetic idea of 'disinterested interest' is an idea that allows us to stand back from the art we make in order to contemplate it, and it stands at the centre of the history of European aesthetic discourse. But there are other aesthetic traditions where art forms engage with the world as part of life.

In the book 'Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia', by Skerritt, Perkins, Myers, and Khandekar, we are introduced to the idea of the 'ever-present', time being something that is bent into a loop, old things being interwoven with new ones in an endless cycle. This 'dance' being the one we occasionally find ourselves lost in, in those moments when perhaps lost in the rhythm of an enfolding piece of music or when looking carefully at something as we draw it, we inhabit the moment rather than regard it as something for disinterested contemplation. In times such as the one we inhabit now, we will need to make decisions as to what art is for and we need to understand how art is changing in the way it operates within our society. Art has never been fixed as to how and why it is used, each culture and time period uses it and understands it in a different way and that is why an awareness of other times and cultures is vital, as it allows us to see that there are other possibilities and that no one way to engage with art is right.

Saturday, 20 June 2020

Photography as an extension of drawing

I had several conversations with first year students this year about the relationship between drawing and photography. Because of the apparent ubiquity of the photographic image, there is a strong belief that drawing is not as relevant as it was. I still beg to differ.

Before a camera can be made, all its parts will have been drawn, both for the patent office and as technical drawings that can be converted into information for machines to follow so that the individual components can be made.

When you need to explain how a camera works, diagrams are nearly always used to show how the various components work.

Ridley Scott did all his own storyboards for Alien and of course decided to use HR Giger's drawings for the alien creature.

Van Gogh, although living at a time when the camera was coming into everyday use, still used an old fashioned perspective frame. Do read his letters if you ever have the chance to, because they are wonderful examples of how an artist thinks. He refers to the use of a perspective frame several times in them. In one of his letters to his brother Theo, he complained about trying to work in the dunes, where the ground is very uneven, "This is why I’m having a new and, I hope, better perspective frame made, which will stand firmly on two legs in uneven ground like the dunes". Then in another letter he complained about expenses, "I had more expenses in connection with the study of perspective and proportion for an instrument described in a work by Albrecht Dürer and used by the Dutchmen of old. It makes it possible to compare the proportions of objects close at hand with those on a plane further away, in cases where construction according to the rules of perspective isn’t feasible. Which, if you do it by eye, will always come out wrong, unless you’re very experienced and skilled. I didn’t manage to make the thing the first time around, but I succeeded in the end after trying for a long time with the aid of the carpenter and the smith. And I think that with more work I can get much better results still." Later once he has got to grips with how to use the frame he states, "Long and continuous practice with it enables one to draw quick as lightning - and, once the drawing is done firmly, to paint quick as lightning too.." From: The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh, Penguin Classics 1997.

There is a certain back and forth with artists moving between the idea of using camera obscuras and tracing frames but the fact that images had to be made by hand and often transferred from one surface to another and that they often also had to be re-sized, meant that a squared up image became central to many artists' thinking when it came to composition. The squaring up also allowed artists to link the internal divisions within an image with the external dimensions of the frame.

When you look through the view finder of a camera, you are using a selection frame, one that you can if you want to, add a grid to. This is again something that as an idea began with drawing.

Mathematics and rightness (Includes information on the Golden Section)

Drawing and film

The grid as a cage

The weaving of grids

Friday, 12 June 2020

The frame and the screen

Framing is both a physical and an intellectual idea. The physical act of putting a frame around something operates as if it cuts whatever is framed away from the rest of the world. But it is not quite as simple as that.

Each type of physical framing changes the way we think about what is framed.

This is why when you go to a framing service website they will often have images showing you how the artwork will look framed alongside other items of furniture. However, sometimes within the frame, we have a second frame, or a third or even a fourth.

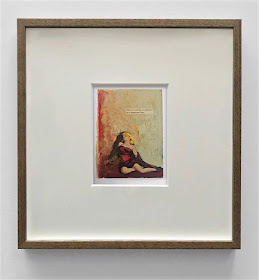

'French matting' uses gold lines to separate the image even further, to enhance the 'aura' of the image. The frame in many ways 'celebrates' the image as a possession. In cutting it out from the world, it can also be a way of making it easier to possess. If you look back at the framed image of a bird in a landscape above, you will also notice that the framing cuts into the edges of the image, (in this case the printing process has cut the edges away to leave a white border, but it is often the window mount that hides the edges of images) a small amount of the image will therefore never be seen and this is another issue artists have to think about when deciding whether or not to have work framed and window mounted. Compare the French matted landscape above with the image below by the Connor Brothers.

The Connor Brothers' presentation fits two ideas together. On the one hand they are trying to reassert the 'objectness' of the image by showing us the edges of the paper by 'floating' the image within a window mount, which itself operates to separate the image out from the world and enhance its 'aura'. The wooden frame, operates to establish both an overall physicality or 'furniture', as well as establishing a degree of separateness from the world, which is furthered by the large expanse of white card between the image and the surrounding wooden frame. We are again looking at frames within frames and the corridor effect is still in play.

It's interesting to look at how as an object's worth increases, both as financial and cultural capital, its framing becomes more elaborate. In this case it is a complex double framing because the older frame that sits around the painting, is itself now an object of cultural capital, the black surrounding frame having the simplicity of a more 'Modernist' aesthetic. We still in effect walk down that invisible corridor into the image, but it is a corridor decorated in both modern and classical styles.

|

O’Doherty looks at the gallery as a sacred space that is like an archeological tomb, undisturbed by time and containing cultural riches. The gallery is thus constructed to give the artworks lasting value; it is a space designed to immortalise the cultural values of our elite i. e. very rich people. Reminding us that galleries are also shops and like most shops they are designed to get you forget the worries of the outside world, the white cube establishing a crucial distance between that which is to be kept outside (the social and the political) and that which is inside (the everlasting value of art). In this case the artwork is framed to ensure that it is separate from the rest of the world, so that the buyer can clearly purchase its aura. In the case of this sort of art the buyer is also buying into the elite world of art and in doing so, establishing a certain set of credentials.

Of course once you understand the game you can enter into it. You can play with the conventions and subvert them to your own ends. Framing and presenting can be a political decision as well as an aesthetic one. But it is important to remember that as the number of paintings are removed from the old collection that we see in the 19th century stereoscopic image above, more and more wall space is revealed, and this wall space operates as a frame. It might not be the golden, florid, decorative thing of the late 19th century, but it is just as much a frame, but this time it is masquerading as a neutral space.

As you can see from this argument, the frame operates in the real world. It operates as a way of giving the observer a cut off or separate space within which to contemplate the artwork, but this operation is a complex one. The space of the frame oscillating between the 'real' world and an ideal space, a space within which art's spiritual or aesthetic values may be cultivated. As the world outside meets the world inside there is a complicated arena within which a certain duality comes into play. Deridda is fascinated by this and he calls it the parergon.

It was Kant that linked the idea of the parergon to that of a painting's frame. On the one hand the frame is seen as an addition or ornament. It embellishes the artwork, but suggests Kant, it doesn't add anything to it. On the other hand Kant sees the frame as an example of something that is neither one thing or another, it is something detached or separate; detached not only from the thing it enframes but also from its surroundings, (the wall where a painting is hung). According to Kant, the parergon is like the gold leafed frame for a painting, a mere attachment added to gain superficial charm or grace, and which could in reality detract from the genuine beauty of the art. The frame belongs neither to the artwork nor does it operate as an article of useful furniture, you can't sit on it, eat from it or keep yourself warm, but in sitting between the two it operates as a permeable boundary, a space between the domain of the artwork and the environment of the room the work is hanging in.

These 'liminal' or 'threshold' moments are essential to an understanding of animism and other forms of web-of-life spirituality that encompass both human and non human understandings of the world and I personally have thought of them as being similar to what Lewis-Davis in his book 'The Mind in the Cave' calls the membrane, or how neolithic peoples perhaps regarded cave walls that were used to support paintings. On the one hand they were just that, walls of caves that you could paint or draw on, but they also served as permeable barriers that allowed people to imagine a space beyond the depictions, one that included the world of spirits and a space in which negotiations between different animals and environments could be performed, often with a spirit guide or shaman.

My understanding of Derrida in relation to this comes via Hegel. Hegel wrote extensively about the master/slave dialectic. The idea being that in a relationship where there is an imbalance of power what can happen is that gradually the one begins to depend on the other and as this dependency deepens the power begins to move from one to the other. I'm not sure how much this happens in reality, but it is a very interesting idea.

Derrida is interested in dualities, he is always looking for openings that allow him to point out that what you think is happening is one thing but in reality it is something else. So in the case of the frame he suggests that what was thought of as an addition is in fact more important than the actual artwork. In doing this he spends a lot of time discussing the position of the frame as both in and out of the world and this is where I would like to bring the screen into the discussion. Like the frame, the screen also sits between one thing and another. It frames the images that appear within it and operates as a physical object in the 'real' world, you can hold it and touch it and treat it like a piece of furniture, but you can also forget it exists and fall into the world it contains.

The formal issue that has always intrigued me is the relationship between the circle and the rectangle that happens between the lens and the sensor. The cartoon above epitomises the problem, the lens has a circular focus that cuts away the rest of the world, thus whatever that part of the world is linked to and shaped by is cut away, but then this cutaway is further re-framed within a rectangle. This action often totally changing the meaning of the event. Framing part of a wider complex event can even reverse its meaning; in the drawing's case, the left hand now threatening the right hand half of the image.

The Edinburgh camera obscura

If you go to see a working camera obscura, such as the one in Edinburgh, the first thing you become aware of is the nature of the curved image. This is what it is like inside the camera, but imagine a frame that is then placed over this circular image, and this is where the film or other photosensitive area is positioned.

The reframing is for a technical reason, the quality of the circular image worsens as we move farther from the lens' point of convergence. As we move towards the edge of the circle, images are dimmer, blurred and smudged. This is due to the lens, not the sensor. The lens converges light towards its centre, which means as you approach its edges you get less and more diffused light, hence the image edge's fuzzy-ness. This can be compensated for by the camera's sensor. A camera sensor compensates for a circular lens that distorts towards its edges in various ways, and because of a range of distortions, including aspherical elements, chromatic aberration, coma, low dispersion, and a high refractive index, has a lot of work to do. Sometimes it is worth looking at technical issues just to highlight how much the nature of a specific medium is shaping communication, so in this case because we are looking at how framing in photography effects meaning and the fact that framing is also a way of minimising but not eliminating lens distortion, I'm going to try and non-scientifically pass on some information.

At the centre of the problem with a lens in relation to focus is field curvature. Curvature of field, is a natural aberration of all lenses, due to their curved structure and how light moves through them and onto a flat plane. The edges of an image can therefore appear soft or distorted compared to the sharper central area. One of the most difficult things to resolve is chromatic aberration, which is when a lens can't focus the different colour wavelengths all at the same point. Wavelengths of light enter a lens and disperse as they pass through it, in order to get all the different wavelengths to come back together at the point of the sensor, these wavelengths need reorganising in order to become focused. Some very high quality lenses can do that, but there is always some difference in diffraction, the problem is technically called colour fringing. A drawing will as always clarify the issue, so let's look at a few technical drawings of the issues involved.

Spherical Aberration is caused by light rays entering the lens and not converging at the same point. This impacts on image clarity, sharpness, and resolution and is more likely to be seen further away from the centre of the image.

We still haven't quite squared the circle, which is why we still rectangularly frame photographs, when the lens is circular and the resultant image is circular too. The corners of a rectangle are further away from the centre than the middle of edges to the left, right, top or bottom, therefore if there is going to be distortion it will be still be revealed in those corners. In fact early cameras often had circular plates such as Thompson’s Revolver Camera from 1862 and 'button' cameras, designed to make small images button sized and shape that could be actually worn like a button. So it wasn't as if the circular format hadn't been considered. The frame as a rectangle, is a powerful concept and somehow it feels right to slice out recorded segments from life with a hard straight edge rather than a circular one. The telescope and the microscope both retain the circular form that reflects the shape of a lens, but as soon as we wanted to record directly what was seen through these optical devices, it was the picture within a rectangular frame that was the right format.

As soon as an image is made it has to fit a 'rectangular' world. Walls are rectangles and so are tables and shelves. Its easier to make right angled frames and film on a roll or as a plate is easier to use with rectangular formats. So there are a lot of simple practical reasons for retaining a rectangle for the photograph, but they are all linked to our overall shaping of the world with geometry. Cave paintings were not in rectangles, it is only when geometry begins to impose itself on construction methods that the circular or more organic form becomes relegated to history.

Buildings have been built using geometric principles for thousands of years, but the idea of the frame in relation to a moveable image is quite recent. It is believed that Egyptian Fayum mummy portraits from around 2,000 years ago were made before the person died. They were then hung on a wall until they died and then the portrait was fixed onto the coffin. Whether or not this is true, and there are arguments about how they were used, these images were portable and they would have been placed around the painter's workshop and probably taken into various residences in order for the artists to catch a likeness of the person. There are traces of a surrounding frame on many of them, there frames may have been to fix them to the coffin or to display them on a wall or for both reasons, whichever reason is right, these were portable images that were at one point framed.

Although borders, or columns acting as frames in ancient art were used to divide scenes as well as provide space for ornamentation in both pottery and wallpaintings, the first wooden frames surrounding images as we know them today appeared on small panel paintings in twelfth and thirteenth century Europe. Often painted onto one solid piece of wood, the area to be painted was carved out, leaving a raised border around its edge. The outer edges were usually gessoed and gilded, before any painting was done, which was often the last part to be completed. Much of the meaning was embedded in the cost of the materials and records from this time emphasise the cost of various materials in craftsmen's contacts, the idea of worth being given to an image by artistic invention was something that would have to wait for the Renaissance.

The use of mitred moulding strips for making the edges of panels came later, and gradually replaced the simple wooden moulding strips that were attached to the outside edges, especially as larger pieces of wood became harder to get hold of, because more and more of Europe's forests had been cut down for fuel as well as for ships, furniture and housing.

The image above has a frame built around it, (an engaged frame) the frame is deeply carved out, the golden space that the figures exist in being a religious space rather than an actual space, the frame being in effect a spiritual building or architecture to place the iconic image of Mary and Jesus within. The frame is used to give the effect that you are stepping from one world into another, an idea that artists in western Europe will return to many times.

As you can see a frame is a complex idea and one I shall probably return to again and again. It links newer forms of image presentation with older ones and has always been related to cutting something out of reality and making it special.

The TV when looked at historically has had a wide range of framing concepts engaged with it, and the particular time periods within which these surrounds were developed also have stylistic impacts on the situation. Because the TV was always associated with the idea of 'modern communications' it was also often placed in a containing surround that was designed to state that modernity.

The state of the art TV screen immediately above has a very thin black border and we are often sold an idea that suggests this border is so thin, it creates no separation between you and the reality the TV depicts. The ultra real 'high definition' screen, allowing you into a world that is as real as the one you are in. Although this frame is wafer thin, in some ways the belief in a new 'realistic' technology is not that dissimilar to the belief in a religion.