Representing music

Time lapse image of a bird in flight

Every now and again I like to look at those very basic visual forms that are also entoptic images, and wave forms are one of them. I have touched upon wave images before; they are like zig-zags, and are related to the way we try and depict moving water, especially the sea and they are often associated with the various ways that we try to visualise music. As I'm very interested in energy flow and how something that appears to be one thing such as a solid mass can either be converted into energy or represented as an energy field, the wave form is something that helps me to both visually and mentally weave thoughts together about these issues, so forgive me but I'm about to go on another tangental weaving run in order to find out what I am getting at.

I first became interested in entoptic forms after reading The Mind in the Cave by David Lewis Williams. The text explores ideas in relation to the origins of image-making. He attempts to relate the foundations of art to the nature of our own consciousness and how we perceptually experience the world. In doing so he looks at Upper Palaeolithic European cave painting and he links the development of shamanic rituals with experiencing the world of the dark cave and parallels between the hidden mind and the hidden interior of the earth. A lot of Lewis Williams' text is devoted to passages between things, (energy flows), for instance the wall of the cave that is used to make images on becomes a membrane through which the world of the everyday can touch the world of the spirit. One of the key developments he picks out is that of self generated entoptic images, generated by the brain when derived of normal visual stimuli, such as when we are immersed for long times in darkness, gradually dissolving into hallucinations of remembered forms, such as animals that are vital to the survival of the tribe and becoming the starting point for a type of image making that could operate as a conduit between material and psychic states. In this process he sees the origins of abstract symbols, like dots and zig-zags and waves alongside iconic forms, images that have a physical resemblance to what is being signified, such as drawings of horses, bison and lions and this introduces other issues about representation itself and various approaches to 'realism' or 'verisimilitude' thousands of years before the camera came into being. Did our ancestors 'find' existing images in the rocks and other surfaces they used to depict things on and simply clarify them, or could they render images from scratch? Did they draw from memory or was there any form of observational drawing practice? Many depictions of animals are well observed, so did artists from this time simply have better memories of animal form, or did they take time to look so that they could bring fresh memories of recent perceptions into their cave depictions. I.e. did they actively work on being able to render these forms, or was it simply that some people were better at drawing animals than others?

The shaman figure became central to this type of experience, being the guide who learnt how to control an environment that flickered between different states of reality and the spirit world. Shamans knew how to re-enact the stages of animism, or the entry of human minds into the lives of the landscape and its inhabitants and the entry of the world's various animal and environmental spirits into the minds and bodies of humans, by using drugs, chanting, drumming and images that would often be found flickering in tallow made lights. In a semi-dreamlike state our ancestors would enter a cave and emerge from it after a shamanic experience as if reborn. In this situation Lewis Williams feels was also born 'art' and as such it would always be associated with transformative experiences.

The wave form is fascinating for myself because it very elegantly straddles the abstract, the abstracted and the formal issues surrounding representation. In doing so it can carry ideas about energy flow through various disciplinary areas and demonstrate that they are all in fact variations of the same idea, that everything is in reality some sort of vibration, an awareness that supports the interconnectedness of everything and the fluid nature of our experience. Flow is central to this, the continuous change that we experience, being one of constant energy and material exchanges.

Perhaps if I start with waves in the sea and how we understand how they operate, as this very physical understanding eventually leads on to how we can think about both quantum and sound wave forms.

Waves in the sea are partly a result of the Earth's relationship with the moon. The moon's gravity pulls the ocean water on the earth towards it. Because the moon rotates around the Earth sometimes the moon is closer to one side of the earth than another, as it changes its relationship, it pulls the ocean water towards it and this constant changing pull results in tidal waves. So the energy of gravity is transformed into the energy of water movement. This monthly cycle is one that can also be seen to affect many other aspects of our life on Earth and is therefore a powerful signifier in itself.

Most waves are caused by wind. Wind-driven waves, or surface waves, are created by friction between wind and surface water.

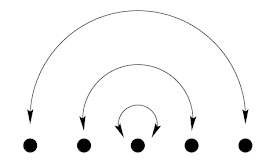

Both gravity; (gravitational energy is the potential energy associated with a gravitational field, which is converted into kinetic energy when objects fall towards each other), and friction; that can also be converted into kinetic energy, can be thought of as types of energy containers and transmitters and waves are created by these energies passing into and through water. Waves transmit energy, not water, across the ocean and that is what is interesting about them. Because this is about the fundamental idea of matter carrying, converting or transmitting energy from one place to another, wave mechanics become useful as a way to think about other forms of energy transmission. A diagram illustrates the issue clearly

The water stays in one place, revolving on the spot as it bobs up and down, but the energy travels longitudinally, in this case from left to right.

It is interesting to compare the propagation of waves through a cracking whip with how waves carry energy through sea water. When a whip is cracked, the whipper moves an arm up and down, which

imparts energy to the handle end of the whip. This motion of the arm creates a kinetic wave in the whip. This wave propagates through the whip and

by the time it reaches the tip of the whip, that tip is moving at supersonic speeds, which is why you get a loud cracking of a whip. There is no way the whip hand can move at the

speed of sound but the velocity of the whip's tip as we can see becomes supersonic. It is in some ways easier to think about the whip and energy transfer, than a sea wave, because we know the material of the whip cant go anywhere, it is just moving up and down, but in the up and down movement something complicated is also going on.

Images of a whip being cracked. 1: The initial curve given by the user's rapid back and forth

motion. 2: The curve has moved out toward the end of the whip, and the

portion of the whip that is on the outside of this curve has decreased. 3: This is just before

the curve reaches the tip of the whip. 4: When the curve does reach the tip, supersonic

velocities occur and the whip cracks.

Wow, all that energy coming from a decreasing curve.

So how does it work? Time for another diagram. Point A represents the end of the whip held by the

user and moved with force P(t) at velocity v. Point B represents the

tip of the whip. X represents a fixed point on the whip

toward the handle. Y represents an expanding section of

the whip from X to a point that is at the same position as

the tip. Z represents a shrinking section of the whip that is

the size of the arc from the tip to the curve. The total length of the whip is X + Y + 2Z. As energy travels along the length of the whip, it has shorter curves to carry it, therefore eventually the short curve of the tip of the whip will move twice as fast as it moves at the loop of the whip. The energy within the big curve of the whip hand's initial movement has to be contained in the small curve of the tip and this is expressed by increased speed. The whip lines as captured in the time lapse photographs are also like drawn lines and you can feel the energy changes in a curve as you draw it. The energy from an arm movement, just like with the whip, is transmitted via the pen, that is itself subject to friction drag as it moves over the paper surface and the energy expenditure captured in the frozen mark, just as the whip energy is captured as it is released by the high speed photography. Each linear mark made can therefore be regarded as a type of wave form carrying energy.

Drawing of a tomb, Chapel Allerton cemetery, Leeds

In the pen and ink drawing above, several energy systems are seen to converge. The energy of looking is itself translated into the pen strokes that make up the drawing. The plant life is transferring the sun's energy into starches, whilst at the same time their visual forms are energised by moving air currents, both facts represented by pen strokes that have more arm/hand energy movement in them than the marks representing the tomb. The energy of the marks in this case being more to do with the flicker of the eyes needed to see this complex form. There is also an intellectual awareness that a tomb like this represents another related idea of energy transformation, that that takes place when a body dies. Some peoples believe that at the beginning stages of death, the body's energy field starts to separate. Accounts of near death experiences have alluded to perceived changes in how the body's energy field manifests itself during the advent of death. People experiencing being drawn up, lifted, or sucked from their body. Some people remembered a sensation of their whole body going out through their head, others a sensation of a peeling away of their skin as they are being released from their body. (Peck, Corse & Lu, 2017) However on death itself, finally all the energy leaks out. Peck, Corse & Lu, (2017), argue that several non-western conceptual frameworks believe that electromagnetic fields underlie the pattern and organisation of biological systems, including traditional Chinese and Indian Ayurvedic medicine. 'The putative energy “life force,” referred to as prana in Ayurvedic medicine, and qi in traditional Chinese medicine, it is believed flows through pathways called meridians in the traditional Chinese system, or nadis and chakras in the Ayurvedic system. Free flow of this “life force” through the body is thought to support health, whereas disturbances or blockages in the flow of this energy are thought to cause impaired function in organs and tissues, and ultimately illness.... Putative subtle energy centres, convert fast-moving energy obtained from the environment into slow-moving energy in the body. They serve as collection and transmission centres for both subtle and biophysical energy, interfacing with physical organs'. (Ibid) Whether or not we believe in these types of ideas, underlying them is the concept of energy conservation and transmission. I might look at the body as a chemical energy deposit, that slowly releases its energy back into the surrounding environment on death. A tomb and in this case one that is designed to look like one belonging to a Roman citizen, represents an attempt to hold onto the energy flow in order to preserve the memory of someone who has died. Part of the effect is the making of this tomb out of stone. Spirals and plant forms are carved into it, a way of freezing or solidifying things that are normally fleeting and in constant flow. The whole tomb now however beginning to weather away, as rain and wind and ice and snow expend their relative energies to erode and dissolve the stone away. By drawing the tomb in a field of open wave like rhythmic marks, it is as if all the various energy flows are gathered together in one and in doing this an image is produced that will hopefully communicate existence as more like a vibrating pattern than as a solid reality.

Wave energy is also a central component of quantum mechanics.

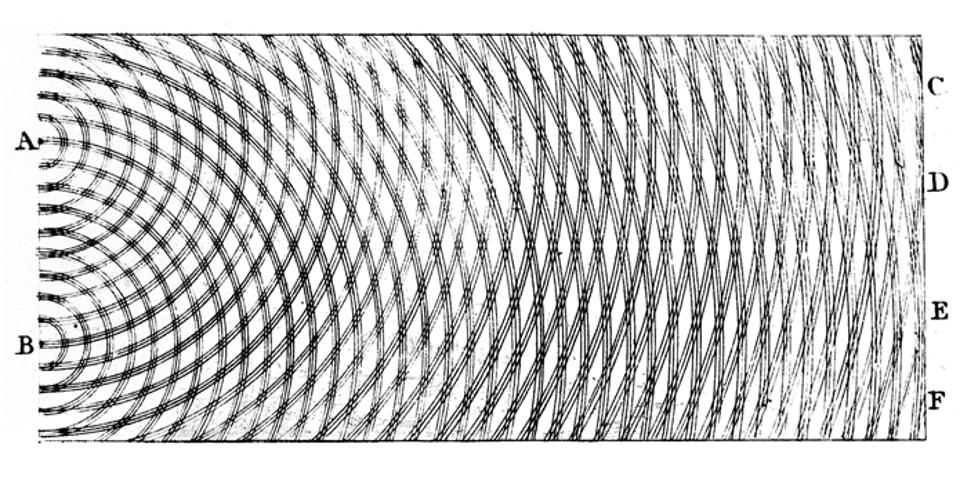

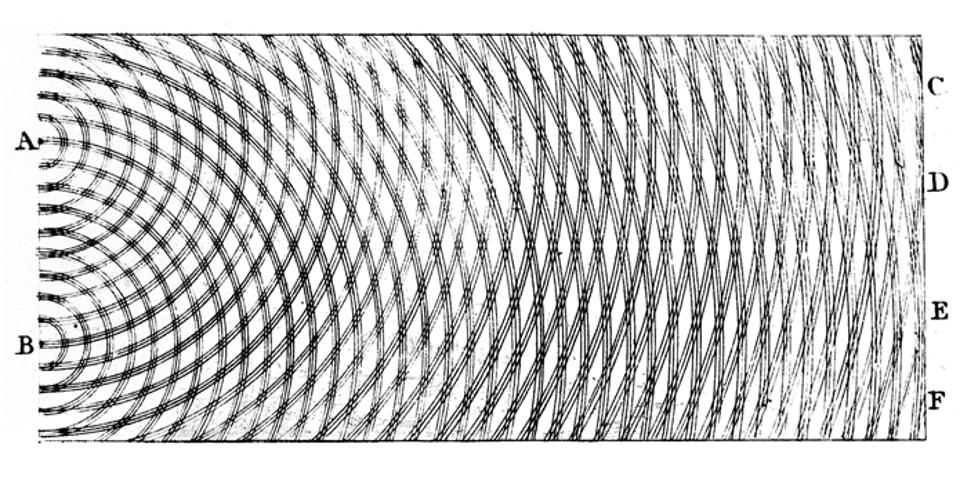

The wave-like properties of light, originally hypothesised by Christiaan Huygens, used an image derived from observations of water. Like waves in water, light waves encountering the edge of an object appear to bend around the edge and into its geometric shadow, which is a region that is not directly illuminated by a light beam. This behaviour is analogous to water waves that wrap around an object, instead of being reflected away.

The combination of an interference pattern with alternating regions of constructive (additive) and destructive (subtractive) interference is a hallmark of wave behaviour and as well as operating in water, it is seen in light and other electromagnetic energy types. However there is the dual nature of quanta to also consider, as they behave as both waves and particles depending on how you interact with them. Experiments have though revealed a wave-like behaviour for many different forms of matter, including forms that are significantly more complicated than the point-like electron. Composite particles, like protons and neutrons, display this wave-like behaviour as well. So the wave goes deep down into the structure of the universe, indeed physicists are looking to mathematically describe the wave function of the universe as a whole. A fluctuation of a quantum wave being perhaps at the heart of how everything began.

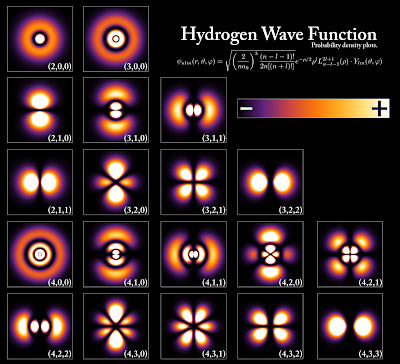

When developing a way of defining wave functions of an electron it was gradually realised that you needed three co-ordinates just as you do when defining a point using an x, y, z axis system. You need a principal quantum number that relates to the average relative distance of an electron from the nucleus and thus its energy level; the Azimuthal Quantum Number, which describes the shape of the region of space occupied by an electron, which in turn will define how the electron sits in the space it occupies and the Magnetic Quantum Number, that describes the orientation of the region of space occupied by an electron with respect to an applied magnetic field. The image above illustrates an electron in a hydrogen atom visualised at different probable energy levels. Quantum mechanics cannot predict the exact location of a particle in space, only the probability of finding it at different locations. The brighter areas represent a higher probability of finding the electron.

The images that result from the process of visualising quantum wave functions are very similar to those we find when visualising sound or acoustic waves. A visualisation of the wave forms generated by a piano as an octave is played, being very similar to the one used to visualise the wave functions of an electron. Sound is a type of energy made by vibrations. These vibrations create sound waves which move through mediums such as air, water and wood. When an object vibrates, it causes movement in the particles of the medium. This movement is what we call a sound wave.

Sound waves like waves in the sea are longitudinal waves. This means that the propagation of vibration of particles is parallel to the energy wave propagation direction. When the atoms are set in vibration they move back and forth. This continuous back and forth motion results in high-pressure and a low-pressure regions in the medium.

Sound as such doesn't exist, however the rapid mechanical vibrations of various elastic bodies is transmitted to auditory nerves of mammals such as human beings, and are then translated by the brain into what we hear as sound as a way of understanding what is happening. Things need to be moved or struck so as to make them vibrate, and as this happens we observe another energy exchange.

One of the best visual illustrations of how all this works is the Rubens tube sound wave visualisation, which graphically shows the relationship between sound waves and sound pressure, and which works as a type of sculptural oscilloscope.The original Rubens’ Tube used a four-meter section of pipe that had about two hundred holes across the top which were evenly spaced apart. Both ends of the tube were sealed shut, flammable gas was pumped into the pipe, and a speaker was attached to one of the ends. When the tube was filled with the flammable gas, there was only one route for the gas to escape through, thus creating a row of diffusion flames across the top of the pipe. Since the pressure inside the tube was equalised, the row of flames would stand at the same height. As soon as you play sound through the attached speaker, the height of the flames then changes. The height differences that you see are equivalent to the wavelength of the sound being played. The sounds that we hear are audible vibrations that require a medium to travel through. In the Rubens’ Tube, the sound waves that we hear from the music are traveling through the flammable gas within the tube. As the sound travels down the length of the tube, localised pressure areas will occur. When these areas of pressure are higher, the gas will escape the surrounding holes faster, creating taller flames. When the area of localised pressure is lower, the gas escaping the surrounding holes will cause shorter flames. These high and low-pressure areas are created by the sound waves traveling through the gas. In this way a spoken poem could become a fiery sculpture.

A Rubens tube: the sound wave is changing the internal gas pressure

Most of us are now used to editing sound on a computer and as we do we often see a graphic representation of the sounds we are editing in oscilloscope form. The image of three sound lines at the top of this post is a typical example. However for myself seeing a guitar string vibrating is perhaps the most fundamental idea, reminding me that the mechanical energy in a curving finger can be transferred to a taut metal string, which in turn transfers its metallic vibrational energies via the air to my ear. The fact that I cant see the air, makes the process far more magical, an unseen energy is out there and at times its propagating waves have affected me deeply.

One of the fundamental things that art can try and do, is to visualise the invisible, be this the spirit world of an animist or the emotive feelings I have when hearing certain music and at the centre of my visual understanding of all this, is the wave form.

If art is still capable of offering a transformative experience, I suspect it is in the making of structures that allow for the contemplation of this sort of awareness. In particular drawing as a way to make images has a breadth that allows us to communicate a scientific principle with a diagram, use materials as metaphors that reflect the way things operate out in the world, be a symbolic language that can carry ideas, as well as being able to present all these aspects together as a simultaneity; everything, the materials, the image and the way it is drawn, all these things can be seen and perceived at once, a wholeness which is in itself a deep metaphor for existence. Because of this, even at its most basic level, for instance when making an observational drawing of the perceived world around us, drawing can be a wonderful means of capturing a flow of ideas and percepts within a material framework that externalises thought and coheres it within the frame of a small sheet of paper.

References