The autonomic nervous system

I have become very interested in how our body's nervous systems are used to create maps of awareness, which enable us to respond to what is going on in both our outer and inner worlds. I'm trying to use my understanding of these 'maps of awareness' as a sort of platform or underlying support for the images I am trying to make as an artist that emerge from a fusion of inner and outer perceptual awareness. My understanding is that animals have for millions of years been attempting to use various nervous systems to map or diagram what seems to be going on, both without and within the various bodies that have evolved over time, so that the complexity of reality can be understood and acted upon. These maps have been made in several ways and it is in the interconnections between them that we make sense of what information is out there and in particular the role of the peripheral nervous system as a controller of 'feeling tone' interests me. My attempts to visualise the more peripheral aspects of perceptual experience by working with interoceptive information, (see) could perhaps be supported by more thinking about this aspect of neurobiology, especially as mapping is such an important aspect of how I think about drawing as a way to visualise experience. So first of all a couple of my own 'maps' drawn to get me to think about how internal and external awareness interconnects.

The body inhabits various energy fields that we think of as an outside the body world

Energy fields within the body pass through its outer membrane, just as those from outside pass through and into the body

It is the movement between inner and outer awareness that fascinates me and this interpenetration has become a focus for both my intellectual and perceptual engagement with art making. For instance at the moment I'm very aware of various dimensions of pain and the fact that they are located in different parts of my own body map. I have plantar fasciitis in my left foot, this means that as I put my foot down to the floor I have a sharp pain in the heel, a pain that radiates down the tendon that goes underneath the foot. This pain is very intense first thing in the morning but wears off gradually during the day until it is a dull throb. My lower back went into spasm yesterday when I went to pick up the grass cuttings whilst mowing the lawn. By bedtime I was in agony but this morning it is much better, but still delicate and sensitive and I know exactly where the pain lies, in that arch of the lower spine, which in my case is too arched. I have slight toothache in the upper left side of my mouth and this has been there since visiting the dentist last week to have a broken tooth sorted out, this is not a problem, more an awareness and the back of my hand is itching and the red circle marks of insect bites are still there; another gardening memento. I could go on, but you get the idea. At this very moment I would say I'm more aware of these internal body issues than external ones, but all it needs is a ring of the doorbell and the perceptual balance could be changed dramatically. This flow is what makes life as it is experienced so fascinating and it offers a complex, rich subject to an artist.

But now some more technical detail.

The peripheral nervous system consists of nerves that branch out from your central nervous system into the body's main mass. (Waxenbaum et al. 2019) It relays information from your brain and spinal cord to your organs, arms, legs, fingers and toes and it consists of two distinct and separate evolutionary systems; the more recent somatic nervous system, which guides your voluntary movements and an evolutionary much older system, the autonomic nervous system, which controls many of the activities we do without us having to think consciously about them. The autonomic nervous system regulates certain body processes, such as blood pressure and the rate of breathing and it helps regulate the internal organs, including the blood vessels, stomach, intestine, liver, kidneys, bladder, genitals, lungs, pupils, heart, as well as sweat, salivary, and digestive glands, in response to both internal and external messages about the changing state of the environment. It has two response divisions; the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. When the autonomic nervous system receives new information about the body and/or the external environment, it responds by stimulating body processes, usually through the sympathetic division, or inhibiting them, usually through the parasympathetic division. The communication system involves a nerve pathway whereby one cell is located in a main processing section of the nervous system, the brain stem or spinal cord and another is located in a cluster of nerve cells (called an autonomic ganglion), which are connected with the various internal organs that need controlling. So by either stimulating or inhibiting these organs in doing what they do, the system controls internal body processes such as blood pressure, heart and breathing rates, body temperature, digestion, metabolism, chemical balances, production of body fluids, urination, defecation and sexual responses. I.e. most of what is going on to sustain our daily lives. For example, when the sympathetic division acts on the heart and blood vessels it increases blood pressure, whilst messages from the parasympathetic division decreases it. The two divisions work together to ensure that the body responds appropriately to different situations. Because we don't see how this works, we have to imagine what it might be like. Just as the changing echo sounds of a submarine sonar system might be listened to in order to visualise the shape of a nearby whale, imaginative images based on stories told in order to illicit representations of the feeling tones of someone's body might be used to develop images of what unseen things might look like.

In 'The Strange Order of Things' by Antonio Domasio, the idea of neural mapping is introduced.

'At some point, long after nervous systems were able to respond to many features of the objects and movements that they sensed, both inside and outside their own organism, there began the ability to map the objects and events being sensed. This meant that rather than merely helping detect stimuli and respond suitably, nervous systems literally began drawing maps of the configurations of objects and events in space, using the activity of nerve cells in a layout of neural circuits. .........imagine the neurons wired in circuits and laid out on a flat board, where every point of the surface corresponds to a neuron. Then imagine that when a neuron in the circuitry becomes active, it lights up, something akin to making a dot on a board using a marker. The ordered, gradual addition of many such dots generates lines that can link up or intersect and create a map'. (2019, p. 76)

Because we are so good at creating these imaginative maps of what we cant see, we have externalised the skills, so that we can build all sorts of cognitive maps in our minds that relate to external perceived experiences. A cognitive map is a type of mental representation that helps us to acquire, store, recall and decode information about the relative locations and attributes of experiences found in both real and/or metaphorical or invented spatial environments. Cognitive mapping then gives us a parallel process whereby we know where we are in space and how that location is related to other locations. Mapping can also add value to these places, such as where the best places to eat are or what areas to avoid because they are dangerous. What the implications of this mean are that before we made that very basic first drawn map, perhaps one that was scratched out using a stick in soft earth, we had developed the capacity to map out those relationships inside our body/minds. Not only that, but we had also developed representations of pain location as well as feeling tone. For instance a tightness in the chest might be due to stress or a lightheadedness due to sexual excitement, but we in some way knew where that tightness was located. These feelings are with us from the moment our nervous systems begin to operate. Therefore not only is the body's map known and used as a model before we begin to map out the environment it inhabits, but as the body grows an awareness of its environment, the map it builds is one based on its initial cognitive mapping of itself, which includes emotional awareness.

There has been some evidence for the idea that cognitive maps are represented in more than one way. (Jacobs et al 2003) One is the bearing map, which represents the environment through self-movement cues. These are vector-based cues that create a rough, 2D map of the environment. Another is a sort of sketch map that works using positional cues. The second map integrates specific objects, or landmarks and their relative locations to also create a 2D map of the environment. The integration of these two separate maps with other sources of information, such as memories of touch or awareness of the body, gradually shapes a growing awareness of the environments that people inhabit. Our bodies are very simple in many ways, they are bilaterally symmetrical and we have our main sense organs located at one end, therefore body maps can have a left / right, top / bottom structure and we apply this to the external world as well. What particularly interests myself is that scientists believe that individual place cells within the hippocampus correspond to separate locations in the environment, with the sum of all cells contributing to a single map of an entire environment. The strength of the connections built up between the cells represents the distances between them in the actual environment. In effect our physical structure is amended and reshaped in response to experiences, just as a map on paper you make or draw from personal experience, is composed of a constant re-drawing and editing in order to get a closer and closer account of the information you gather.

Cognitive mapping allows us to make complex maps of data

Related, but in many ways very different, are the Body Maps that are often used by medical practitioners to visually pinpoint where on the body a medical condition is affecting a patient. This helps them accurately track the physical progression of an illness so that care can be applied accordingly. A wide selection of conditions can be recorded whereby changes to the surface area of the map over time are important, such as bruises, scalds, infections, skin conditions or swellings as well as being a way to give precision to letting others know where a broken bone or pain may be, or the site of a previous injection. These maps tend to be outlines of the front and back of a male or female human. You can get them in adult and child size, but all the parts of the figure are related in a 'normalised' position and no accounts are made of the different psychological or or internal maps made by individuals, in these cases 'one shape fits all'.

Body map. Head (area 1, 2, 23, or 24); neck (area 3 or 25), shoulders (area 4, 5, 26, 27); arms (area 6, 7, 8, 9, 28, 29, 30 or 31); hand (area 10, 11, 32, 33); ribs or chest (area 12 or 13); abdomen (area 14 or 15), back (area 34, 35, 36, 37), buttocks or hips (area 38 or 39); genitalia (area 16), legs (area 17, 18, 19, 20, 40, 41, 42 or 43); feet (area 21, 22, 44 or 45). Adapted from Margolis, Tait, & Krause (1986).

However if we look at diagrams of how we actually sense the world, we find that the body is sensed very differently to the two front and back figure drawings above.

The body modelled by amount of sensitivity to touch

You will know yourself that when you have toothache for instance, your internal model of the body will be focused directly around the tooth that is causing you the pain. Just as London drags our attention to the south east of the map of the UK, because it is so important, a bad tooth drags the awareness of your internal body map to the mouth.

This sort of thinking is very common, we are all focused on different things because of self interest. These maps of the USA are hopefully self explanatory.

From: Jacobs, F. (2022)

Just as the map of the USA morphs according to interest and from where the viewer is coming from, everyone's internal cognitive map of their own body differs.

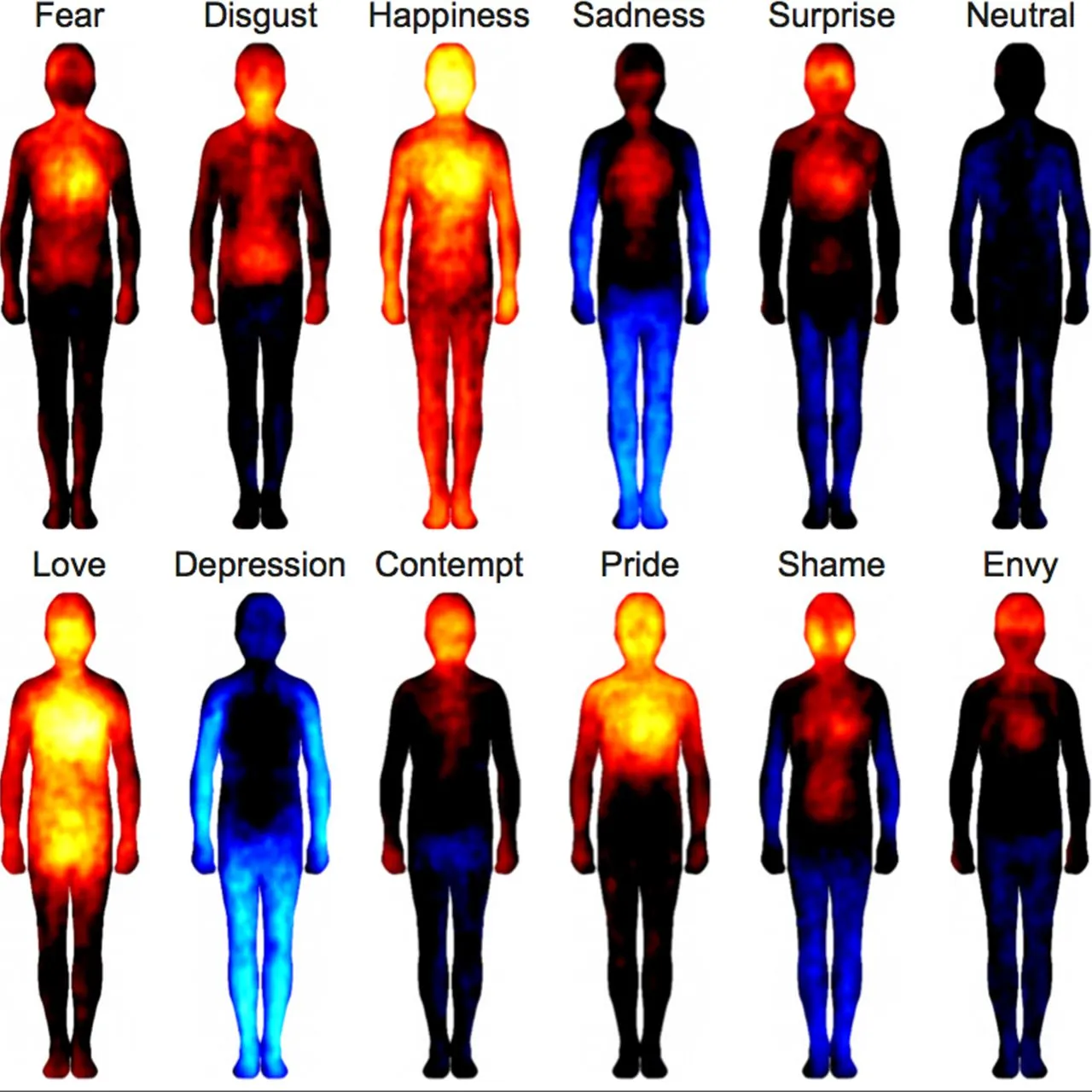

Another aspect that overlaps this area of visual thinking is psychological 'Body mapping', a technique used to identify and position important and relevant emotions such as anger, sadness and love, on a pre-drawn body outline. I was particularly interested in the fact that a study was made using a large sample of people across many cultures and it was found that bodily maps of emotions are culturally universal, (Volynets et al. 2020) especially because I had also read that emotions are not universally pre-programmed, but are culturally conditioned. (Barrett, 2017). This helped me as an artist to feel that it was possible for me to operate in this territory because there was enough scientific doubt to offer spaces in which to be inventive, especially in relation to what Barrett calls 'constructed emotions'.

Emotional body maps

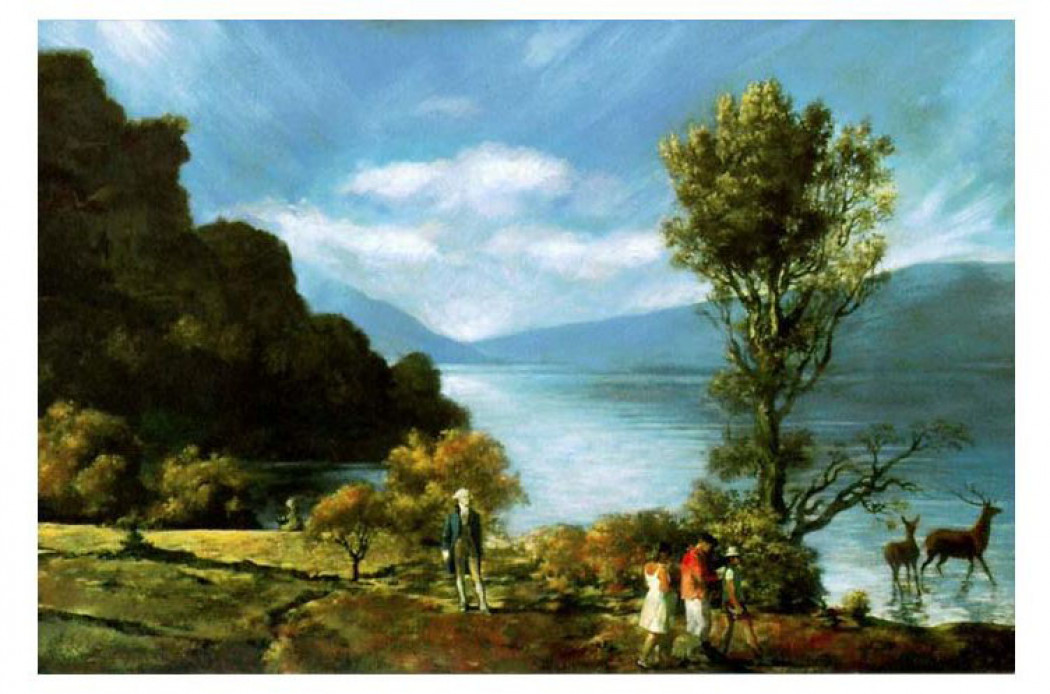

The standard human shape in the diagram above is for many people acceptable but the colour range feels far too predictable, but I suppose if you are trying to communicate across several cultural barriers, then a certain crudity of emotion / colour correspondence is to be expected. It does though seem to me to be all too neat, it looks like a carefully designed answer, rather than the confused mess of colour, shape and emotion that I have had to deal with when I have spoken to people about visualising their emotional worlds. I'm reminded of Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid's work whereby they statistically researched what each country's population thought would be a most loved and most hated painting, and then making visible the results. The final body of work was very carefully designed and illustrated the points they wanted to make very well, but once you 'got it', you 'got it' and that seemed a long long way away from the actual experience of encountering either a painting or a landscape.

America's most wanted painting

Russia's most wanted painting

Both Komar and Melamid's work and the psychological body maps of emotions in relation to colour are based on surveys and according to quantitative research standards they have to be large enough to justify the resulting statistics, a too small number can easily be biased and the readings too subjective. However statistics don't help much in pin pointing those intrinsic qualities of our individual experiences. Science begins by looking at external studies and samples as types of explanations, but subjective experiences are part of what it is to be and this is where I feel art comes into its own. Seeing for example involves various sorts of probing; you are trying to make sense of the spatial chaos that confronts you. As you do you process both what things are and where things are and these recognitions are mixed together to make some sort of awareness. Action and feedback is slightly different in response to these different experiences, but we know our sense of 'where' is being constantly modified by our body movements; eyes change focus and as our body moves into new spaces it encounters constantly changing information that it senses by recording changes in touch, sight, smell etc. But what things are is something that emerges from previous experiences that are mapped against information coming through. You are one thing, constantly changing location amongst other things that are also moving. You are constantly updating the 'whatness' by adding in previous knowledge, such as friend or foe? Perception is therefore not like a passive screen whereby we simply receive qualia, it is more like a form of two way traffic whereby sensing and acting operate in tandem. The whatness of things being in flux, just as much as the 'whereness' of experience; is that stripy thing a tiger or a flickering shadow cast by tall grasses? As I run away I see that it was really a shadow and I slow down, but it was best to run first just in case it was a tiger. The fear was real however and that is an integral part of my feeling tone and as the actual moment fades into my past, the emotional memory embeds itself into my being. As Peter Godfrey-Smith puts it, 'systems... modulate the interpretation of sensory information by the animal's registration of what it is presently doing'; (2021, p. 86) there is a coordination between sensing and acting. When I make a drawing or a ceramic object, as I sense what I'm doing I act in response to what I'm sensing. As I make my images, I would like to think that the process of their making is no different to the process of simply being alive. As animals evolved and were able to coordinate multicellular sensing, parts of their bodies became 'maps or reflections of fragments of their surroundings'. (Ibid, p. 84) Inner and outer worlds therefore were contiguous.

If we go back to those very first cells and their ability to communicate, we return to the basics of electrical flow. A cell has to manage the chaos of atomic vibrations that become much more real when you are such a tiny thing. One way to bring order is to regulate electrical energy flow, or charge and it uses the control of ions to do this. A cell's membrane keeps some things outside and others inside it, but it needs to communicate through this membrane and let selective things go through. It often uses ion channels for this, which enables cells to adjust their overall charge in relation to the outside world, a sort of tuning, as well as to develop controlled flows of ions, which can function as a basic form of sensing. Godfrey-Smith uses an example of a cell coming into contact with a particular external chemical change, which opens a channel and lets in ions which then as charged particles set new events in the cell into motion. (Ibid, p. 31)

Perhaps the most important issue arriving for myself as an artist is some sort of confirmation that meaning is tightly bound up in materiality. This means that the old scientific critique of the artist as being too subjective fades away because we are not able to be 'outside' of the world in order to be able to observe it. We are aspects of the physical world, totally integrated into its activities, rhythmically enmeshed into all the other rhythms of vibrating energy fields. Our neurons are not just excitable cells, but are oscillatory devices and rhythmic things have as Huygens put it, 'an odd kind of sympathy between them', (In Godfrey-Smith, p. 191) and as an artist seeking a metaphoric understanding I am perhaps just looking for 'that odd kind of sympathy that exists between things'.

For instance I have just found out that the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, have been given an award to support the creation of a detailed map of the anatomy of the human vagus nerve; one of the largest and most critical nerves controlling organ functions like heart rate, breathing, digestion, metabolism and immunological responses.

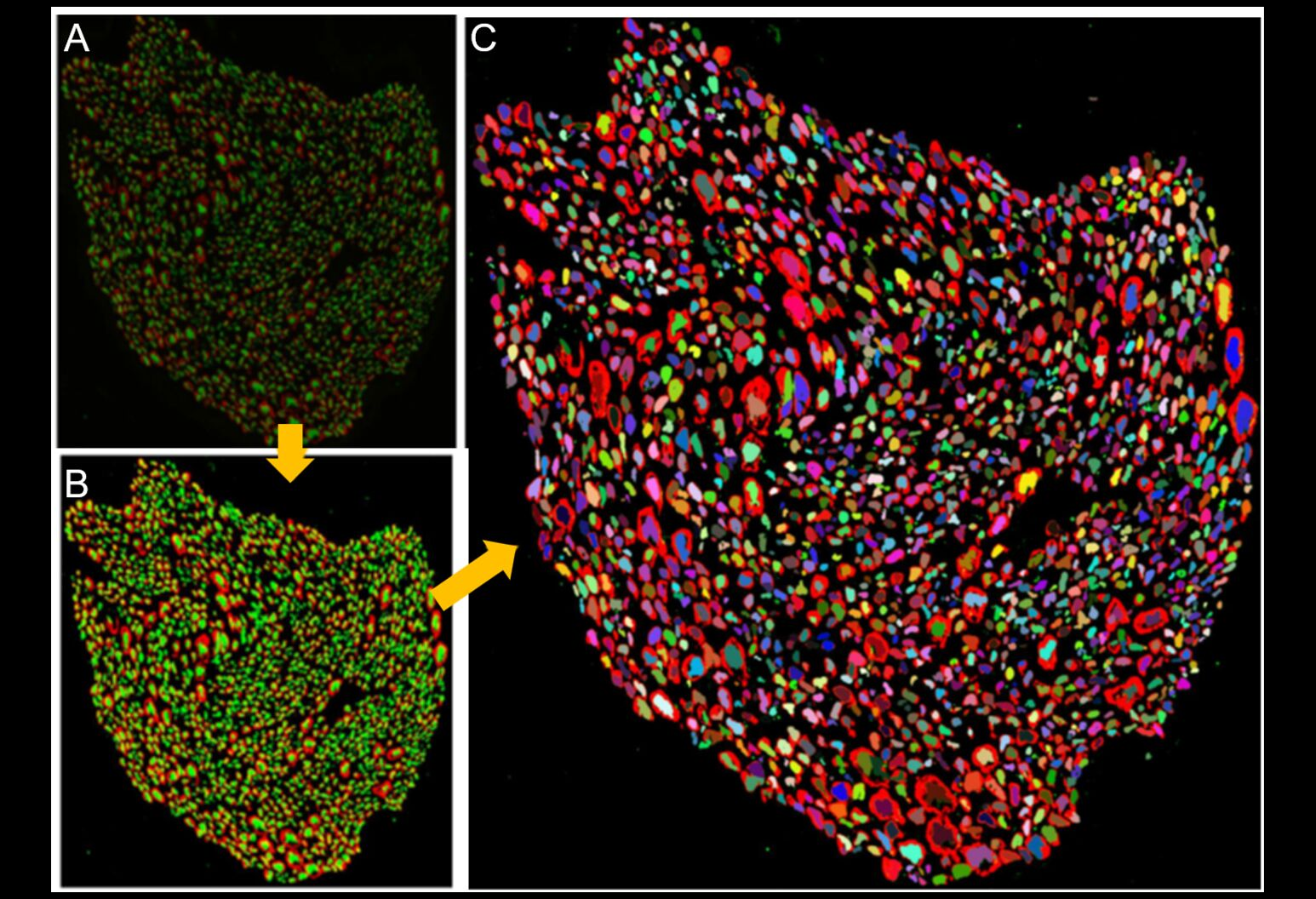

One bundle of the human vagus nerve (A), computer enhanced (B) and further analysed at a single fibre level (C).

The map will show the anatomical connectivity of vagus nerve fibres from the brainstem, where the vagus nerve starts, all the way down to organs in the neck, chest and abdomen. At the moment how sensory and motor fibres are arranged inside the vagus nerve and pathways to different organs are essentially unknown. The vagus nerve, which means “wandering” in Latin, runs from the brainstem to most of the body’s major organs. The nerve is not one solid structure but is instead made up of more than 100,000 sensory and motor fibres, grouped together in several bundles, or fascicles, inside the nerve, eventually forming branches that connect to the organs like the heart, lungs, oesophagus, liver and intestines. When functioning properly, the vagus nerve contributes to the maintenance of our body’s homeostasis. However, diseases like Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis, chronic heart diseases, diabetes and even some cancers are associated with inflammation and abnormal vagus nerve function. This research has already provided images that I could imagine at some point feeding into my own thinking about how the body has developed its own maps. The process of mapping being nested, going from initial maps made in the mind to these new ones that will rely on computer enhancement and the techniques of electron microscopy. The thinking behind this project emerging from minds structured in particular ways that allow them to think of ideas in certain ways, ways that are always responses to information being processed internally and externally; this two way process reflecting the fact that the vagus nerve itself is transmitting information in both directions between the brain and body.

After all this reflection of what it might be like inside I'm still left with an unknown continent, one that I can only really explore in my imagination, an imagination that is though fed by what I'm thinking and what I'm reading.

References:

Barrett, L.F., 2017. How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. London: Pan Macmillan.

Damasio, A., 2019. The strange order of things: Life, feeling, and the making of cultures. London: Vintage.

Downs, R. M. and Stea, D. 1977 Maps in Minds: Reflections on cognitive mapping London: Harper and Row

Godfrey-Smith, P. 2021 Metazoa London: William Collins

Volynets, S., Glerean, E., Hietanen, J. K., Hari, R., & Nummenmaa, L. 2020 Bodily maps of emotions are culturally universal. Emotion, 20(7), 1127–1136. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000624

Jacobs, F. 2022 Satirical cartography: a century of American humor in twisted maps Big Think Available at: https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/satirical-cartography-9th-avenue-steinberg/

Jacobs, Lucia F.; Schenk, Françoise (April 2003). Unpacking the cognitive map: the parallel map theory of hippocampal function. Psychological Review. 110 (2): 285–315.

Libassi, M. (2022) Feinstein awarded $6.7M NIH grant to create first human vagus nerve anatomical map Northwell Health: Newsroom, October 25th, Available at: https://www.northwell.edu/news/the-latest/6-7m-nih-grant-creates-first-human-vagus-nerve-anatomical-map

Waxenbaum, J.A., Reddy, V. and Varacallo, M., 2019. Anatomy, autonomic nervous system. National Library of Medicine Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539845/#:~:text=The%20autonomic%20nervous%20system%20is,sympathetic%2C%20parasympathetic%2C%20and%20enteric.