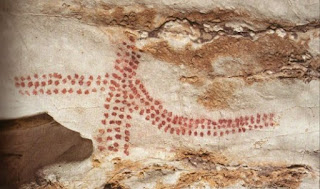

Niaux Cave: Paleolithic dots

El Castillo Cave, Spain: the dots represent a river system

Euclid describes a point as “that which has no part,” it has no width, length, or breadth, in effect it is a location rather than a thing. This immediately interested me because it suggested that if a point is the elemental thing that is used to construct everything else, and that in effect all it is, is a location, then everything is just a cloud of locations. It feels to me as if Euclid was in some way intimating that at a certain level matter or things don't exist, simply relationships in space.

As this blog is about drawing perhaps we need to see how a point is formally represented; above left is a representation of a point within a two dimensional plane and within a three dimensional form on the right. In modern mathematical language a point is described as a 0-dimensional mathematical object which can be specified in n-dimensional space using an n-tuple consisting of n coordinates. (I.e. in three dimensions there are 3 co-ordinates) In dimensions greater than or equal to two, points are sometimes considered synonymous with vectors and so points in n-dimensional space are sometimes called n-vectors. A vector is defined as a quantity having direction as well as magnitude, especially as determining the position of one point in space relative to another. So I now become confused and find my lack of mathematical understanding a real problem. Euclid says that a point has no width, length or breath, but a point can be thought of as a vector, which is a quantity having direction as well as magnitude. I can see how a point is a location and therefore can have direction, but where does the magnitude come in? I'll get back to this.

My first experience of the dot at school outside of geometry was in an art session as taught by my art teacher Mr PC Rudall. I was 12 years old and he asked us all to make images of dots. He suggested that we could mass some of the dots together, that we could change their colours and that we could control the way the eye looked at the page by the way we distributed them. I was gripped by this exercise and remember watching how clumps of dots could be made to feel as if they were an emerging mass and open areas of the white page could be activated for my eyes simply by putting in one tiny spot made by gently touching the point of my brush into the white space. I mixed colours carefully also changing tonal values in such a way that the mark energy of the dot changed. I found out that dark dots seemed to push forward towards me and that some colours would also seem to be more active than others. By clumping dots together, by giving other dots more white space around them, by changing their tonal values and by making them different colours, it seemed as if you could make anything happen. There was one rule, you couldn't make the dots different sizes, they had to be as small as you could make them with the point of an 'O' size round brush. I quickly worked out that everything was different if you used a coloured background and tried out the same idea on sugar paper, for the first time realising that white was a colour just like all the others.

My first experience of the dot at school outside of geometry was in an art session as taught by my art teacher Mr PC Rudall. I was 12 years old and he asked us all to make images of dots. He suggested that we could mass some of the dots together, that we could change their colours and that we could control the way the eye looked at the page by the way we distributed them. I was gripped by this exercise and remember watching how clumps of dots could be made to feel as if they were an emerging mass and open areas of the white page could be activated for my eyes simply by putting in one tiny spot made by gently touching the point of my brush into the white space. I mixed colours carefully also changing tonal values in such a way that the mark energy of the dot changed. I found out that dark dots seemed to push forward towards me and that some colours would also seem to be more active than others. By clumping dots together, by giving other dots more white space around them, by changing their tonal values and by making them different colours, it seemed as if you could make anything happen. There was one rule, you couldn't make the dots different sizes, they had to be as small as you could make them with the point of an 'O' size round brush. I quickly worked out that everything was different if you used a coloured background and tried out the same idea on sugar paper, for the first time realising that white was a colour just like all the others.

Mr Rudall then introduced us to Paul Klee and his Pedagogical Sketchbook, the first element, a line being taken for a walk, described by Klee as getting going or beginning to move by this quaint sentence, "The mobility agent is a point shifting its position forward". So once we had mastered the idea that points were full of potential we were then asked to make lots of drawings of lines, but the dot images were the ones I remembered most powerfully because they were the first ones to impress on me that there was such a thing as a visual language and that I was excited by this more than anything else at the time.

When I was a student at Newport College of Art one of my fellow students Diane Cotton, wrote her final year thesis on 'A history of spots from the year dot', a title I came up with for her one day in the college canteen. She was a graphic design student, so had a much more advanced awareness of the importance of basic design; as an at the time, conceptual artist, I felt I had left behind all those formalist concerns. The foolishness of youth. I hadn't realised that nothing ever goes away, you just have to think about things differently.

There are some amazing ideas contained in the idea of a point. The point that is the centre of a black hole is a singularity, with an infinite density, its mass being condensed into a zero volume. Space and time ceasing to exist as we know them and the current laws of physics not applicable.

When I was young all the TVs were cathode ray models. When you turned them off the capacitors continued to discharge for a few moments, therefore the cathode ray tube would continue to emit electrons. As these were no longer being controlled to move in their regular horizontal pattern, they just came straight out and made an image of a white spot, which would then disappear into blackness. It was a powerful image at the time and began to stand for the end of things. In particular the static on screen suggested something other worldly, the final white dot in blackness somehow star like in its finality. I found it hard to find a old clip of how it used to be, the simulation below isn't quite right but you get the idea.

The most interesting issue here is of course how technology changes our ability to use metaphor. That screen of white static and the final dynamic dot was though not far away in visual look to the sky at night, which is probably why it had so much appeal for science fiction enthusiasts, it sort of brought the mysteries of the universe into the home.

The first dots to make some sort of cosmic significance for human beings were of course the stars as seen from Earth at night. From time immemorial our ancestors must have stared at that mass of tiny lights and must have imagined all sorts of possibilities for the way they might be connected, for Western peoples the one the Greeks came up with somehow stuck, but it is interesting to look at other possibilities.

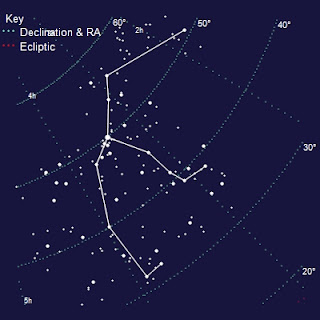

Perseus

Some cultural variations of patterns that include the star Mirphak in their shapes

In the top image of Perseus we begin to see another set of dots and their meaning is slightly different, they are much more to do with measurement and how we divide up the sky and any other boundary-less expanse, such as the sea. I have touched on these lines before in a post on the dotted line but didn't open out the more precision orientated metaphors and the way these are related to our vision of space and of course speculative futures.

The central vanishing point in perspective, now in a gaming video becomes something to pass through, it is a sort of black hole doorway into hyperspace.

The old target form, now looking much more precise and because these images are made in light lines on black backgrounds, they relate directly to our experience of the stars at night. I've used the idea myself in some recent prints.

I drew some library shelves and used their vanishing point as a way of finding specific information in particular books found at the location indicated as the central spot. However I also wanted to suggest a zoning in on this area and as part of the project was about the underlying quantum energies operating on a subatomic scale, needed a visual metaphor to support this. I wanted to make my audience aware that I was operating in a human sized space/time and that there was also a subatomic world operating at exactly the same time. By using the sharp point of a real compass to reinforce the central drawn point and by making the dashed curve of the compass lines light and the background black, a series of associations via science fiction films of how a quantum universe might look, were built into the image. Well I hoped so anyway.

These points are very much about fixing direction. In the case above this is a modern day computer interface that works to adjust tyre alignment. The square that surrounds the central dot suggesting a very high degree of accuracy.

This accuracy is often accompanied by an idea of 'sighting', a dot set within four right angles being perhaps the clearest example of a visual metaphor for this.

A swarm of birds

Swarms of insects or birds can be thought of as masses of dots. This takes us back to those images I made as a boy under the tuition of PC Rudall. A collection of dots and spots of different sizes has an appearance of both movement and volumetric mass. The important thing is to carefully adjust size and weight of the marks. You could of course try and copy an image like the one of a swarm of birds but far more interesting to invent ones for yourself.

Dots make spaces and forms

These groups of dots can communicate different types of concentration and dispersion, can be used to show a movement from regularity to irregularity, express depth by implying both distance and nearness as well as having the ability to imply other elements by being clustered into shapes that echo other forms. Above all it is a wonderful visual experience to spend time looking at a field of spots and dots of various sizes. A small three inch square can have an appearance of cosmic significance if you can only just let go and allow your imagination to take over.

These are dots associated with the visual language of a more natural world where there are a very different set of metaphorical possibilities. For instance the nucleus of a cell is often rendered as a spot or dot.

The basic elements of a cell

When looking for an image to describe the relationship between a dot and the idea of a simple cell I came across this drawing below. It was captioned. 'How to draw an animal cell' and seemed to sum up perfectly what I was thinking about.

How to draw an animal cell

The centre of a circle is a point, and when you actually draw one with a compass a faint indentation is always left where the point of the compass dug into the paper. Every compass drawn circle in effect is like a diagram of a simple cell. Of course the difference is that a cell is organic and the edges are therefore not geometrically uniform, such a small difference seeming to separate the organic from the geometric. But that difference allows you to draw a series of freehand dots, each surrounded by a quickly drawn line, and in making a drawing of this sort you begin to have a metaphor for the beginnings of life.

Drawing of cells

In the drawing above several more elements have been added but the basic pattern of a spot or in this case two or three dark spots within an oval, allows you to build a wall of cells.

A spot

Detail from Grunewald's isenheim altarpiece

The spotted body of the crucified Christ in Grunewald's painting above, being indicative of the reality of disease and death.

Spots are in this case blemishes and need to be removed. A visual language now linked to the stain.

Not too far distant in visual language is the finger print. Going back to the spots on cave walls these were often made by simply dipping a finger in paint and printing it by touching the cave wall.

A fingerprint can be read as a spot, but it is also has complex linear swirls within, as we look closer, it could be argued all dots become much more complex shapes.

Drawing of a printed full stop when looked at under a microscope.

ReplyDeleteIf you're looking to get a start on learning the new, fun, and profitable skill of web development, then this course is for you. Instead of teaching tedious theory on how to code a website, you'll learn practical knowledge on how to do it.