Léopold Lambert is a

very interesting writer who publishes The Funambulist, an on-line blog that is

endlessly fascinating, this post of his opens out the idea of the body as a

topological surface: The Funambulist

He introduces a way of thinking about the body as a topology.

“The body is a

continuous surface folded many times that interacts with an exterior milieu

whose limits cannot be established because of the impossibility of establishing

a bodily interiority. What

then becomes fundamental to an understanding of the body’s topology is what

Simondon calls “membrane,” that is this folded surface that separates two

milieus (neither exterior, nor interior) from one another. This membrane

constitutes the interface of exchanges between these two milieus and Simondon

sees in these exchanges the essence of life: “all the content of the interior

space is topologically in contact with the content of the exterior space on the

limits of the living being; there is no distance in topology.” (Lambert, 2014)

Simondon echoes Deleuze in his topoligical approach. In 'The Fold', Deleuze explores ideas surrounding folds of space, that both represent movement and invent time. He interprets perceptual experience as that of a body of infinite folds that is woven out of threads of compressed time and space.

Once we begin to think

of the skin as a folded surface, it is not a very difficult step to think of

how a paper surface might substitute for skin, and that drawings might become both flat surfaces and 3D objects.

In medieval times skin

colour was used as an indication of someone’s ‘complexion’ or ‘temperament’,

the colours red, white, black and yellow representing the various ‘humours’

that categorised character and disposition. A balance of heat and cold, dryness

and moisture was required to build an even temperament. One could be choleric,

phlegmatic, melancholy or sanguine. As Wotton (in Connor, 2004) points out in

reference to what painters can and can’t do, “painters cannot imitate, neyther

subject vnto their pensell, the fashions, graces, maners & spiritual

complexios, which either laudable or vitious do cleare or darken beautie”, i.e.

that artists struggle to depict both inner temperament and outward appearance. If

you want to research these things read Steven Connor’s ‘The Book of the Skin’ Available here

The point being that metaphors related to the skin's surface appearance can involve a rich and complex language and that these

languages change over time. As an artist your own investigation into drawing will

often touch upon how surface representation can operate metaphorically, not of course always in relation to human skin, but even when not, you might think about how background research can deepen and open out possibilities for investigation.

If paper is to be read

as skin and if skin itself becomes a subject for investigation you might want to consider some of these issues.

Shape and positioning.

It is not by accident

that we call the orientation of a paper rectangle portrait or landscape. We are

bilaterally symmetrical and are taller than we are wide. A vertically

orientated rectangular sheet of paper reflects this; therefore even without

putting any marks on a sheet of paper we can create a basic metaphor. We can

take this further; an A4 sheet of paper if in portrait position is a very

similar shape and size to the human head. If we start putting a few horizontal

lines across it we easily begin to recognise the divisions of eyes and mouth

and nose.

Think about how you read someone else's face. The scanning of another human being's

bi-laterally symetrical face is very similar to scaning headlines. We design things that reflect the fact that our sensibilities are finely tuned to 'read' how other humans are reacting.

If you attach two portrait

orientated A1 sheets, one above the other, you now have a rectangle very close

in proportion to the standing human figure.

The total surface area

taken up by an average adult human is approximately 1.8m2 to 2m2.

You can calculate the surface area of your own skin by using this body surface

area calculator. If you were developing images that were operating within

a self-portrait tradition would you need to consider this? Would your drawings

contain a more direct message if the paper surface was exactly the same as your

own was calculated to be?

Texture and surface

The surface texture of

paper is of course vital to the establishment of metaphorical possibility. If

using paper it can be oiled, waxed, crumpled and creased, dipped into liquids,

sanded down, polished, folded and scored, scratched into, left out in the rain,

trod upon or shot through with bullet holes. Try scrunching paper over and over

again until it becomes like material and then paint a layer of linseed oil over

it and hang up to dry. The paper itself and the way it is treated holds tremendous

opportunities for metaphorical exploration.

The more you scrunch the paper the more it will become like an old skin

Lauryn Arnott's work demonstrates yet another way that the body can be thought of as an ageing skin and Alex Kanevsky's watercolours show how paper can aid watercolour's ability to suggest skin's opalescent transparency.

Mathilde Roussel's wall mounted pieces move between paper surface as skin metaphor and paper as a casting medium.

Choice of support

Brown wrapping paper

comes in very large sheets, newsprint can come in huge rolls, hand-made papers

come with a wide variety of surfaces, the paper that large posters are printed

on is thick and robust, some papers are mixed with plastics, some plastics can

be treated as flexible supports, walls and floors can be drawn on directly, Wim Delvoye works on live pigs, wallpapers not only

come in long lengths but have wider domestic associations, printed ephemera

carry messages of previous use, tissue papers have associations very different

to tracing papers and all have the ability to be treated as a metaphor for human skin as well as being cut up using patterns and used as a second skin (clothing).

Inuits make kayaks and wetsuits from sealskin. They sew themselves into their kayaks and at one time travelled as far as the Orkney Islands. The islanders thought they were half seals and half men and called them selkies. In the stories the Orkney islanders told the selkies were shape shifters who shifted form by coming out of one skin and entering another. This passage between states could be seen as an analogy, a story that could belong to another tradition, that of artists trying to make flat representations of humans using marks on surfaces.

One very direct

connection we can make with this is the use of sewing patterns. In some ways a

sewing pattern can be seen as a plan for an extended second skin. Different

body sizes are encoded in their production and these are also rich areas for

symbolic meaning, think of the way we call ourselves size 8s or size 10s and

how you worry when you have to move sizes. Inuits make kayaks and wetsuits from sealskin. They sew themselves into their kayaks and at one time travelled as far as the Orkney Islands. The islanders thought they were half seals and half men and called them selkies. In the stories the Orkney islanders told the selkies were shape shifters who shifted form by coming out of one skin and entering another. This passage between states could be seen as an analogy, a story that could belong to another tradition, that of artists trying to make flat representations of humans using marks on surfaces.

An Inuit sealskin suit

Old pattern cutting paper already has a surface that looks like skin

We map our bodies in

different ways and each culture has its own approach to this, for instance

Chinese acupuncture diagrams allow us to think about the interconnections

between the skin’s surface and what lies beneath.

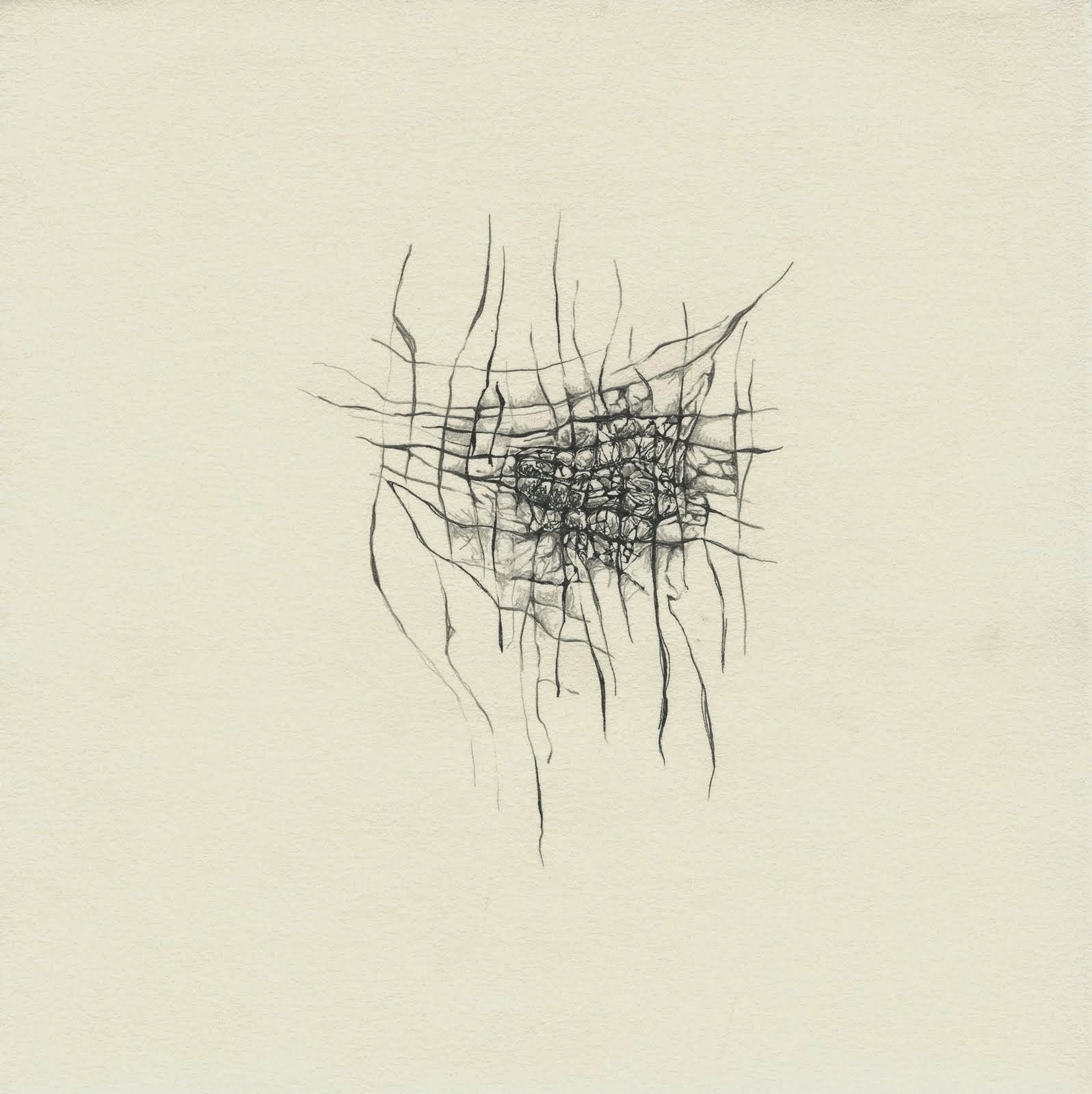

Mapping the body can

be done in many ways and by using very diverse sets of information, the artist

Katie Lewis has developed her whole practice around this. Link

Body maps can also be

the site for narrative, in the image below two women have made body maps to

describe the experience of living with HIV. Link

Chinese acupuncture diagrammes go into extreem body detail, in particular the 'map' of the ear suggests an intense investigation of every inch of the skin's surface.

The combination of the image of the body as portrait and the idea of it as a map, can create a facinating fusion between two approaches.

Tarryn Handcock

You can of course

turn everything around and make the surface the drawing material. In this image

(below) Dragan Ilic uses pencils pushed through a surface to create a drawing

tool.

Which bring me to the drawing tools themselves. You can make your own tools and the way you make them can further the metaphor. Tools can scrape, scratch, puncture (the tattoo), rub, smooth or irritate the skin (paper surface).

See also:

You could think of these surfaces as 3D realisations of acupuncture diagrams

Which bring me to the drawing tools themselves. You can make your own tools and the way you make them can further the metaphor. Tools can scrape, scratch, puncture (the tattoo), rub, smooth or irritate the skin (paper surface).

Kate Lewis's drawings use sharp points to puncture paper surfaces.

One final word on skin. Of all the different surfaces on which you can

make marks vellum is the most charged with meaning. The word itself comes from the Old French Vélin, which means "calfskin” and it is a surface made of mammal skin. In order to make

it you have to kill and skin an animal, then clean the skin, bleach it, stretch

it on a frame, and scrap the residue of meat and fat away. To create that

lovely taut flat finish the scraping is alternated by wetting the whole

skin and drying it in the sun and then finally the surface is sanded with

pumice and limed. Animal vellum can be made from virtually any mammal including

humans. The best quality, "uterine vellum", was made from the skins

of stillborn or unborn animals, it is so

thin that it is translucent, just like human skin.

Preparing human skins for display

Wim Delvoye tattooed pig

I am of course only

scratching the surface of this subject and will at some point return to it.

Flesh

No comments:

Post a Comment