William Smith Geological map of Great Britain 1815

The more I think about interoception and the world around me, the more I realise that we are shaped by a combination of what lies beneath the surface of our bodies and what lies below the Earth we stand upon. Again it is diagrams that we rely upon to tell us what is there and as I have been having to teach a few sessions on the World Building and Creature Design MA, I have been reminded in particular of how signs of the geological evolution of the Earth and the physiological evolution of our bodies are physically present deep within both.

Perhaps we need to go back to Greek times to see why we can understand things in this way. R. G. Collingwood in his 1945 treatise on the Idea of Nature, had this to say about the Greek view of the natural world;

'Since the world of nature is a world not only of ceaseless motion and therefore alive, but also a world of orderly or regular motion, they accordingly said that the world of nature is not only alive but intelligent; not only a vast animal with a 'soul' or life of its own, but a rational animal with a 'mind' of its own.' (Collingwood, 1960. P. 3)

At one point Collingwood describes Greek thinking on this issue as an analogy. He states that before we know the world we know ourselves and when we look at ourselves we see that a complex series of constantly moving physical parts are kept in equilibrium by a mind directing all the various components. Therefore early philosophers argued that nature as a whole must work the same way. It is intelligent and seeks to maintain autonomy and survive by making decisions that are advantageous to its survival. Interestingly back in 1945 Collingwood was using this argument as a contrast to what he was then calling 'modern' or 'scientific' thought. Concepts such as the embodied mind and ecosophy were yet to enter the world of philosophical academia in England, but Collingwood's description of Greek thought would be very familiar to anyone who has read the Gaia hypothesis. The Gaia concept proposes that living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings to form synergistic and self-regulating systems that maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet. Lovelock and Margulis put the idea together in the 1970s, but any believer in animism from two thousand years ago would have also understood the idea. It was the Judeo-Christian concept of a monotheistic God that removed this embodied metaphor, instead it was God the great creator, the engineer that lay behind everything, who was responsible for why things worked in the way they did. This took away nature's autonomy or as God put it:

'Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.' Genesis 1:26

Instead of the world being regarded as a giant complex intelligent interconnected physical being, a thing that we had to both commune with and fit in with if we were to survive, we were given the idea that we were in some way better than nature and that we could 'have dominion' over it.

However the ancient idea that the world of nature is not only alive but intelligent and that it is a vast animal with a 'soul' or life of its own, still seems to have traction. Sometimes we use the term 'bodyscape' to describe the metaphorical use of body imagery in relation to landscape. Ancient metaphors that understood the earth to be modelled on the human body are sometimes seen as being one-way relationships; the ‘landscape as body', but more recent changes in philosophical thinking, in particular the material turn and object orientated ontology, point to a two way process, 'the body as landscape' being just as significant.

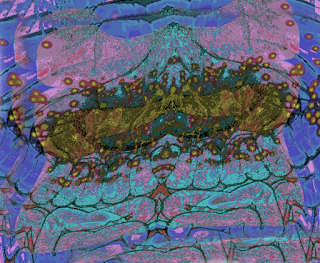

Pioneering stratigrapher William Smith is credited with creating the first useful geological map, (see image at the start of this post), and it is very interesting to compare drawings of slices through human skin to slices through the Earth's mantle. The fact that we think of rocks as having veins suggests that we see the layers of geological strata as being analogous to the way we think about our own bodies.

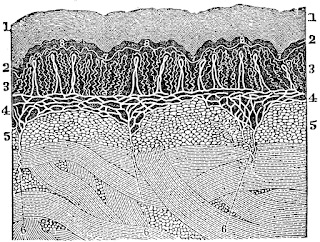

Visualisations of layers of the skin

In the image above numbers are used to annotate the various different layers as we progress down into the human body. For example '1' is the cuticle and '2' its soft layer. '4' represents the network of nerves and '6' three nerves that divide off from that network. The way the cross section is drawn in many ways brings together various ideas of bodies and landscapes, the need to create distinct textural areas being common to both formats, stippling and broken lines being used by both geologists and anatomists to identify different layers.

Veins of molten rock penetrate the layers of the Earth's crust

Geological cross sections

Geological plan view of what lies beneath

Nomawethu: Map of her body, with her personal story of illness

Ntombizodwa

The two images directly above are from a body mapping workshop led by South African artist Jane Solomon. To create these Body Maps, participants filled a life-sized outline of their bodies with handprints, footprints, personal symbols and text. Ntombizodwa states; "Look here where I have painted the virus. On 19 January 2001 I became very sick. Stomach pains and headache. It was summer time, the season of peach and apricot, and I thought that’s why I had a sore stomach."

Greek natural science was based on an analogy between nature as a macrocosm and humans as a microcosm. Nature was viewed as an intelligent organism, just as a human being is. In the same way that we realise that we have a mind that directs our body's operations, it was argued that nature must have some sort of intelligence too if it was to direct its various affairs successfully. Just as we devise ways to portray the interior of our bodies, we find ways to portray the interior of the land that we live on.

A body slice

A slice through a landscape

The more I think about these relationships the more the imagery I use to depict certain states of interoceptive awareness becomes influenced by old maps and diagrams. Feelings are like 'soundings' taken from deep within the body. The body being both its own landscape and an inhabiter of landscapes.

A feeling of internal change

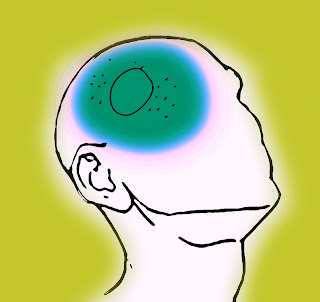

The image, 'A feeling of internal change' (above) was made whilst I had bad stomach ache and was feeling sick. I had been fine all day, doing a glass workshop in the morning and helping out at a busy art book fair in the afternoon. I then walked home, but on the way began to feel totally exhausted. Knowing I had to go back out that evening, I decided to eat a fast snack, that included a spicy onion bhaji and a glass of milk. Whatever the combination of spices and cooking oils was, it did not agree with me and I was doubtful whether or not I would be able to go out again. The image above was then drawn in my sketchbook while I was waiting for my friend to arrive, and then hopefully by that time I would be feeling better. The milk I had drunk, seemed to be helping combat the acid, but I was still feeling sick. While the image was still fresh in my mind, I photographed it and began to add colour in Photoshop. The blue was an attempt to show the change, with the red an indication that the pain was still sharp, but now intermittent.

I was literally grasping around for an image that would communicate an invisible something and as I did I realised I was also sensing it in my fingers and the image is an attempt to show this as well. I was drawing a slice through an imaginary body that was also a map, but a map of an unknown territory and one that was changing rapidly, one that was being felt for by my fingers, even though they could not touch it.

The body and a pain

Interoception includes an awareness of pain, as well as the development of images of pain with which we can at times conquer pain. But it is also about an awareness of feeling tone, of where the body is located in space and other somatic events. Alongside this complexity is a wider awareness of the interrelatedness of everything. There is another aspect of bodily awareness that is a very ancient one, one that has at times been approached under the heading of Tantric Art, and is not just a celebration of the body, but an understanding of the body as being a physical representation of the cosmos itself. Unseen but still sensed experience can I believe be understood as an aspect of the sublime. In the case of interoception, visualisations of these invisible sensations are of a hybrid form that is a composite between visual invention and memories of past experiences, and they rely on physical resemblances with other objects as well as a more abstracted understanding of energy flow.

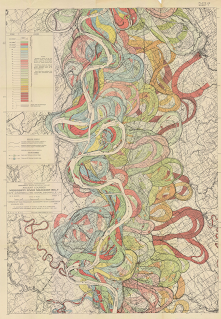

In order to explore a relationship between physical resemblance and an understanding of energy flow, we can look at Harold Fisk's meander maps of the Mississippi River.

Harold Fisk: Meander Map of the Mississippi River

When trying to imagine the human body and landscape being fused together, Harold Fisk's mapping processes, which looked at landscapes over long periods of time, are useful to look at. Harold Fisk's maps represent the memory of a river; thousands of years of river course changes are compressed into a single image and because of this the landscapes 'come alive'. Geological time unfolds into a human time-frame, the maps becoming 'more like us' as they do so. We often point to mapping as a very 'objective' activity, forgetting that as inhabitants of very particular bodies, we are bound to make things that reflect our particular physical make-up and awareness of time. In this case a geological feature is converted into a record of changing energy flows, using shapes and colours and a scale of production, that is little different to an anatomy diagram. As I get older I'm more and more aware of signs of ageing, but forget that signs are layered, and instead of just looking at how things appear to be as they are on the skin's surface, I think I might be better off looking for those signs that are obscured, lost beneath the skin, but which also reveal the past as well as indicating a fast approaching future.

Harold Fisk: Meander map

13th Century English anatomy illustration

Homme 4D

The image 'Homme 4D' reminded me of a time when I used to collect old anatomy drawings, in particular ones that opened out and revealed the body as a set of layers. These disappeared many years ago, but I did find this image on a flickr site, which is another example of how to display a body seen through time as well as space, in this case folding out a series of layered representations.

Fisk's work also reminded me of Nikolaus Gansterer's diagrams, in particular Gansterer's idea of the drawing as a 'score'.

From the Embodied Diagrams series by Nikolaus Gansterer

Nikolaus Gansterer's Embodied Diagrams series derive from a four year research project Choreo-graphic Figures: Deviations from the Line. This was a collaborative project that developed shared figures of thought, speech, and movement reflecting on the specific nature of ‘thinking-feeling-knowing’ operative within artistic practices that seek to represent the body. Drawing was used as a translational bodily process that was able to help the research team imagine a variety of forms in which a drawing of the body can become manifest, materialise, and take shape. Gansterer. points out that, 'The German words for drawing (zeichnen) and for notation, recording (aufzeichnen) share the same etymological root'. Acknowledging this, Gansterer produces 'scores' as imaginative prompts. These 'scores' are used to map the complex 'relation-scape' between body, place and atmosphere, a 'diagrammatic (re-)presentation of embodied knowledge(s).'

He describes his images as mapping the durational ‘taking place’ of something happening live and the subtle processes in the event of "figuring something out". This situation intrigued me, because in my own work I had been trying to balance a representation of a thing with a process, for instance an awareness of a pain and at the same time of the process of feeling the pain and of communicating it, a quite difficult process because it crossed several boundaries. The British 'stiff upper lip' might for instance, make it hard to measure pain's effect on a subject taught to show no emotion.

Gansterer worked in collaboration with the writer Emma Cocker, dancer Mariella Greil and others and their work is available at: www.choreo-graphic-figures.net I was particularly fascinated by the collaborative aspects of Gansterer's research and as I have already been working in collaboration myself, think it is perhaps time to revisit some of the issues involved. The fact that mapping is usually associated with geological terrain is something I don't think I've made the most of and as I have been trying to visualise the invisible, mapping might offer a way of building in signposts or guides as to where things might be located.

Visualisation of a breathing restriction

Visualisation of peristaltic waves

Both of my drawings above are images derived directly from my own personal experiences of responding to an awareness coming from inside the body and they are attempts to visualise for others the feelings that I had at the time. Both images were initially drawn by hand and then scanned into PhotoShop and adjusted until the colour felt right. Photoshop also allowed me to use layers and in doing so I could add diagrammatic details such as arrows or colour used to identify where a centre of a pain might lie.

By visualising something normally invisible to others, perhaps an alternative form of communication could be developed in relation to health matters. In particular in the case of a growing awareness of peristaltic waves, (stomach pains), this might mean that someone should be having conversations about taking exercise or eating more fibre. I think the image of peristaltic waves works well in conveying my own personal feelings, but would anyone besides myself guess that that is what the image is of. I could use an outline drawing of a body to indicate where the sensation lies, but as soon as I do the richness of the imagery is dissolved into a very obvious sign and as that happens the 'feeling tone' is lost and its the 'feeling tone' that I really want to capture. However, by taking 'Homme 4D' as a model, I have tried to develop new images that begin to have more of the visual ambition of Fisk's work and which are the basis for an enfolding or layering of images, colours and textures to suggest somatic experiences.

The thought form of an inner body sensation

Headache

The visualisation of tinnitus

By now I have hundreds of images developed in collaboration with other people in various attempts to visualise their awareness of normally invisible internal sensations. I shall take a selection of these to Porto in July, and use them to instigate a set of workshops designed to assess how transferrable these ideas are. I will be hosting some workshops with hopefully medical staff and students and we will see whether or not there is a common visual language that could be used between both art and medical practitioners, as well as non specialist audiences.

The images below were made when thinking about the body anatomically as a geologically accessible object, a poetics of the cross section.

Innerbody landscapes

References

Collingwood, R. G. (1945, 2022) The Idea of Nature London: Dead Authors Society

Fisk, H.N., (1952) Mississippi River valley geology relation to river regime. Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, 117(1), pp.667-682.

Rawson, P.S., (1973, 2012) Tantra: The Indian cult of ecstasy. London Thames and Hudson

Winchester, S. and Morris, M.D., (2002) The map that changed the world: William Smith and the birth of modern geology. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 2(2), pp.12-13.

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment