Dandelions have historically often been used to represent celestial bodies, each one coming into prominence during the 3 different phases of the dandelion's life. The plant’s yellow flower representing the sun; the dispersed floating seeds the stars and the puffed out fluffy dandelion ball the moon. We have records of dandelion use going back over 4,000 years and fossil evidence of them from 50 million years ago. They are therefore much older as a species than humans and have had much more time to adapt to various environmental conditions. However like humans they are generalists and as such have been able to survive over a wide range of environments. The early 17th century herbalist, Nicholas Culpeper, found it to be a ‘virtuous herb’, and when consumed in the spring he states, "you may look a farther, you may see plainly without a pair of spectacles”. Its supposed ability to sharpen our eyes could be a clear metaphor and alongside its cleansing quality in the treatment of obstructions of the liver, gall bladder and spleen, you have a restorative concept that could also lead to images of healing.

In folklore the dandelion got its nickname, the ‘shepherd’s clock’, because the flower opens after sunrise and closes at dusk. They are of course very easy to grow, Dandelion seeds germinate quickly, generally taking from three to six weeks to sprout, and are able to survive a light frost. It is an aid in activating compost as well, making Dandelions useful agents for getting a wasteland's transformative energies moving quickly and keeping those energies moving. It is an essential component in a natural healing process, whereby if we leave a plot of wasteland long enough it will become a vital, thriving community of interrelated species. Therefore dandelions are an aid to their surrounding environmental community, helping to transform environments so that more delicate plants can grow; also providing a wealth of nutrients to a wide range of animal herbivores and omnivores and providing bees and other insects with nectar during times when other plants are not in flower. You could think of the dandelion as a catalyst for other garden reactions, its presence signalling that a healthy plant community was being built.

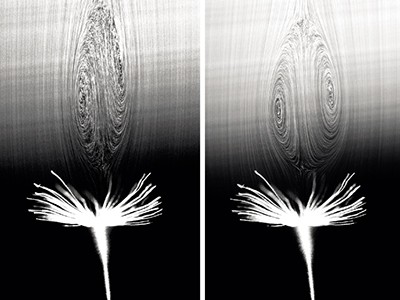

The dandelion's parachute of bristles is arranged so that when the pappus falls, air flows between the bristles and creates a low-pressure vortex. When captured using special imaging technology, this vortex is rather like a tiny ghost that travels above the pappus and yet is not attached to it, an invisible familiar that generates lift and prolongs the seed’s time in the air. An article in 'Nature' by Cummins, et al. (2018) explains that the key to this lies not in the bristles of the pappus, but in the spaces between them.

'If projected on to a disc, the bristles together occupy just under 10% of the pappus’s area, and yet create four times the drag that would be generated by a solid disc of the same radius. The study shows that air currents entrained by each bristle interact with pockets of air held by its neighbours, creating maximum drag for minimum expenditure of mass. The pappus’s porosity — a measure of the proportion of air that it lets pass — determines the shape and nature of the low-pressure vortex'. (Cummins, et al. 2018 p. 417)

What interested me most about this however was the fact that the dandelion had evolved to respond to the thickness of the air, something that I had only thought animals could do. Like the dandelion's parachutes, tiny insects, such as the featherwing beetle have evolved to swim through thick air. Featherwing beetles do not fly using traditional wing shapes, they swim through the what is to them, thick viscous air, using ‘paddles’ made of bristles. The difference between plants and animals is perhaps less than we would like to think. If we think of a dandelion more as a series of interacting processes, then its seeds floating away are just one of several aspects, all of which are equally important to its life cycle, and one aspect of this life cycle is that its seeds need to fly.

Stars and Dandelions by Kaneko Misuzu

Deep in the blue sky,

like pebbles at the bottom of the sea,

lie the stars unseen in daylight

until night comes.

You can’t see them, but they are there.

Unseen things are still there.

The withered, seedless dandelions

hidden in the cracks of the roof tile

wait silently for spring,

their strong roots unseen.

You can’t see them, but they are there.

Unseen things are still there.

In the 1950s the BBC used to have a series of children's programs most of them involving string puppets. The Flower Pot Men was the story of Bill and Ben, two little men made of flower pots who lived at the bottom of an English suburban garden. Julia Williams was the voice of Little Weed, a dandelion with a smiling face, who was always shown growing between the two large flowerpots that were the homes for Bill and Ben. The program was for myself as a child a powerful visual influence and as I got older became one of those personal image banks on which I could draw upon, the further back in my personal timeline they emerge from, the stranger they seem but somehow also more comforting. The talking weed in particular would sometimes come to inhabit my dreams, eventually of course I would need to draw it, a process that at times can be vital to the construction of what I see as an externalised mind. I'm afraid this is another very personal account, but by thinking of artworks as externalised minds, I am able to think about how they work for myself and why I need them.

Appreciating the persistence you put into your blog and the detailed information you provide. Keep up the good work.

ReplyDeleteplastic food container supplier malaysia

cny cookies packaging

Hello, this is a nicely explained article. Your piece was very informative. I had never heard the issue presented in that light. Thanks for your hard work.

ReplyDeletesocial media management agency malaysia