Seeing a plant, seeing a garden: Agnes Waruguru: 2020

Dreams of more and more and yesterday: Agnes Waruguru: 2020

Waruguru's delicate images are partly sewn, partly drawn and partly painted. She touches her surfaces delicately as if almost frightened to make a mark, she is an artist that is dealing with an uncertain certainty that feels to me a right and proper way to go about our relationship with the world. For too long we have valued those that seem to command respect because of their certainty and clear vision, but I'm afraid too many of those visions have now been seen as self-aggrandised flag waving. "Look how wonderful I am", says the artist, while the world burns and the forests die.

Columbine (An illustration from the 1950s)

The flowers of the columbine outside my door are now dropping and being replaced by seed-heads, and every time I pass this plant I'm reminded that Durer made a beautiful image of the same plant way back in 1526, and that the name Aquilegia, is derived from aquila meaning eagle because of a similarity between the shape of the petals and eagles' wings. In medieval times, columbine was thought to be eaten by lions and because of this connection, rubbing the flower between your hands therefore gave you the courage of a lion. But for the Romans it was a flower beloved of the Goddess Venus, so you could wear it as a love token. The more you delve into a plant's history, the more connections you will find, it eventually becoming something mystical, something entwined with the ghosts of its ancestors, the columbine of today, being the columbine of 1526, just as it was the flower to clothe a pixy's head and to soothe the heart of the goddess of love.

Sketchbook drawing of a now gone to seed columbine outside my door

Diagrams of bee flights

David Jones

David Jones had an approach to the natural world that also feels as if it is both uncertain and certain. His vision enables him to with great delicacy, intuitively picture the atomic dance of flowers and spaces in such a way that in this image, the garden moves inside and overpowers the interior space. The vibratory buzz of a bee, is perhaps the driving force behind this approach to composition.

Apple tree: Gustav Klimt

Klimt's 'Apple tree' is an image that suggests that there is no definite edge between the tree and its environment, the one slips into the other. It is an image that any one of us could see just by stepping out into the garden. Klimt's images are though also cosmic visions, the flower garden dissolves into life energy, these could be paintings of galaxies or the interior of an atomic cloud; like Van Gogh's sunflowers and Monet's waterlilies they go beyond seeing the world as a collection of objects or things and picture it as an event, a happening rather than a record.

Flower garden: Gustav Klimt

Nathan Hawkes continues the tradition of the unfixed image, uncertain but certain, his drawings are never still. His flowing vegetation escapes being bound by lines and his surfaces pulse with energy.

Nathan Hawkes: The double dream of spring: 2019

These images remind me of Markov blankets. It has recently been argued that any living system is a Markov blanketed system and the boundaries of such systems need not be co-extensive with the biophysical boundaries of a living organism. In other words, autonomous systems are hierarchically composed of Markov blankets of Markov blankets, all the way down to individual cells, all the way up to you and me, and all the way out to include the local environment. For instance, in the drawing below, a human being and a tree both dissolve into their surroundings, whilst at the same time still maintain enough of an internal integrity to still be seen as a human and a tree.

Human, tree, air and ground

Seurat

Minjeong An has looked at how her father grows sprouts. Her diagrams set out to visualise both visible and invisible relationships, in the case of the sprouts, she is as concerned to show that her father has to lavish love and care on his sprouts, just as much as he has to water and feed them. I.e. the feeling tone of a human being is as important as the nuts and bolts of a system, such as a need for water and food. Care it should never be forgotten is essential to all the best gardens.

Minjeong An

Minjeong An's work includes drawing using sharp lines, she uses Illustrator as a drawing tool in order to give her diagrams precision and coherence. However because she concentrates on relationships, she overcomes the tendency of line to isolate things.

What I'm getting at, is the reason that we can work powerfully with the garden as a subject matter, just as we can work powerfully with any other subject, is that as long as we can see a series of interconnections, understand or intuit the consequences of any thing's being, we can develop images that in their very making try to communicate things about the situation we have begun to explore. If on top of that we have a view on how we feel about or think about the connections we find, we can shape the process of making images to reflect this view. It's not easy and very few of us have a clear point of view that is easily translated into imagery, but by every now and again trying to feel our way towards an answer, we can have something that keeps us going, some kernel around which we can build a construction that at least feels as if it is meaningful. Hopefully this approach stops us thinking we have the answers, but allows us to continue searching and in that search perhaps we become more attuned to the things that surround us and become better gardeners.

There is as always another story. The Aboriginal peoples of Australia used to draw sacred designs on themselves and in the soil, these designs often using dots and zig-zags, were outlined in circles and encircled with dots and were deeply interconnected to sacred rituals. Their garden was the landscape they existed in and it was something that inhabited them as much as they inhabited it. These designs were for the tribe and the initiated, for people who would understand how the dots and patterns reflected the stories told; stories woven into folk tales of the people, intertwined dreamtime encounters with animals, plants and the landscape. Those who were uninitiated should never get to see these sacred designs, because they would be able to enter the secret places, steal the knowledge of thousands of years and upset the delicate balance of the eco-system. These designs would often be drawn directly into the earth with sticks, and the soil would be smoothed over on the appearance of an outsider.

In the early 1970s Australian school teacher Geoffrey Bardon asked the young aboriginal school children he was teaching to paint their world in their own way. But the youngsters struggled and their parents couldn't understand why they had been set such a task; they wanted to know why he was asking the young people to picture things that it was the job of the old people to know. I thought this was very interesting, because in the west we associate children with creativity and celebrate their fresh if often clumsy approaches to depicting the world, but we rarely look at older people as the custodians of image making.

Because of the private nature of certain ritual links to image making the initial group of men who Bardon worked with decided to work out which aspects of the stories could be told and which ones had to be withheld from public view. Men from at least half a dozen different language groups worked on this together. They worked out jointly how they could express very significant aboriginal stories without upsetting the requirement for non-initiated people not to have access to the meanings. Once this was resolved it meant that the elders could paint their stories. At that time there was little interest in Aboriginal culture, most of the government directives in Australia were directed at trying to make aboriginal peoples let go of their traditional beliefs and to embrace Western culture. Bardon supplied art materials to the group of elders and with help from him, they began to paint their stories by transferring their depictions from desert sand to paint on canvas. Because of the concern that the more sacred and therefore secret aspects of the things they they painted were being seen not only by Westerners, but Aboriginal people from different regions, these early translations therefore had their special secret elements abstracted into dots to conceal their sacred meanings. These first paintings to come from what became known as the Papunya Tula School of Painters were never intended to be sold. They were created by the Aboriginal people who had often been displaced, and living a long way from their original home country, as reminders of landscapes that they still inhabited in their minds, landscapes that they still felt they needed to protect, even as they represented them in paint, by changing some of the more significant features. These paintings were in effect visual reminders of their own being. They painted the lands that they belonged to and the stories that were embedded into them. These paintings were visual assertions of their identity and their origins. The original colours were restricted to variations of red, yellow, black and white produced from ochre, charcoal, sand and pipe clay, however when these paintings became popular and saleable, acrylic paints were introduced and much more vivid colourful paintings ensued. The fact that the original colours were also representations of the various earths of the landscapes they lived in, was quickly forgotten.

Even though the original patterns were changed in order to remove secret meanings, the basic structures and ideas about how to depict the world remained intact and the work produced had a resonance and a visual power that broke through the difficulties associated with the conditions of the people that began producing work of this sort. For instance the artist Michelle Possum Nungurrayi is the daughter of one of the group of men brought together by Geoffrey Bardon in the 1970s, her paintings even more abstracted from the initial forms as were developed by her father, but the rhythms and visual pulses emanating from her work are still effective and some of the forms she paints still echo the symbolism that was came from original sand drawings.

Some basic symbols

Coda

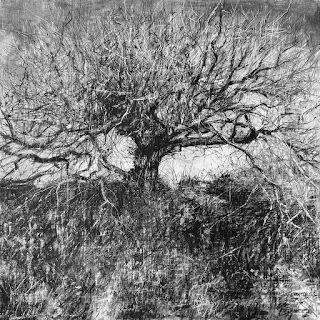

Every now and again I'm asked whether it is worthwhile putting work into competitions. These always cost money and you very rarely get through to the exhibition itself. I tend to be ambivalent about the process, sometimes I think its a total rip off but at other times I decide that its one of the only ways that an artist can get his or her work noticed. For instance Andrew Barrowman has just won The Bowyer Drawing Prize. He received £500 for his pencil and charcoal drawing, 'Tree Study'. Little recompense you will I'm sure all agree for a tremendous drawing that will have taken hours to make and years of art making experience to allow him to control markmaking within such a complex space. A short video was made of his response to winning and he was obviously delighted. A very traditional artist, he shows that you can still make a wonderful image out of the things you see on your local walk. His drawing process of working into charcoal on a gesso ground has allowed him to give a vibrant energy and life to this image of a tree that he encountered in his sketchbook recently. If he hadn't won the prize I would have probably never seen the drawing, so perhaps it is a good thing to apply for these competitions sometimes.

See also:

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteyour blogs are outstanding class i love it.

ReplyDeleteClear Tarpaulin

Thanks for sharing this informative post.

ReplyDeleteExtra Thick Clear Tarpaulins 350gsm Clear Reinforced Tarps