On the 7th of June 2020 John Cassidy's statue of Edward Colston, a 17th century slave trader, was pulled down by an angry crowd and thrown into the river. The statue had already been graffitied in earlier attempts to respond to its implications, and when it was fished out of the water the damaged statue became a problem for the city. Should it be put back or not? The statue has just been put on display, but this time as part of an exhibition designed to ask questions as to its role and whether or not it should ever be re-erected. The exhibition however has come in for criticism from the right-wing media for the way the statue is presented, lying down on its back and still covered in the graffiti that had been daubed on it.

I have looked at graffiti as a street language in an earlier post and we could have no better illustration of the division between low and high class values as in the relationship between the visual language of the statue; cast bronze and an idealised three dimensional realism, and the visual language of the graffiti; spray paint, pooling colour that collects in indentations and the traces of hand gestures rather than any attempt at representation. Colston was initially celebrated in bronze and set up on a plinth above his fellow citizens because of his philanthropy. The received narrative is that he was elevated to this position because he devoted his later life to good deeds within the city of Bristol. Elevated is a good word to use in relation to a statue like this, the bronze itself is 8ft 8 inches high and the plinth is 10ft 6 inches high, the head of Colston therefore looks down from a commanding height of over 18 feet above the ground. Around the sides of the plinth are two scenes from Colston's life and a third image of a maritime fantasy. A plaque on the south face bears the words "Erected by citizens of Bristol as a memorial of one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city AD 1895"

Most of the spray paint was applied to the statue before it was toppled, therefore someone must have climbed up to it in order to do this. This physical act is itself a sign of challenge, the plinth is meant to keep people at a distance, a distance that was overcome by the act of climbing. The toppling signifies the taking of resistance to what the statue represents one step further. The graffiti preparing the crowd for action, the statue already defaced, its presence reduced by the act of marking it, therefore its power was compromised and it was in effect already brought down to earth by being touched by the language of the streets.

Colston's prestige in Bristol was not what we think it was, or have been encouraged to believe. The notion that the erection of the statue in 1895 was undertaken because of popular support for his philanthropy is hard to sustain. The £1,000 that was needed to pay for it was very hard to come by, the final amount only reached after the statue had been unveiled. The original proponent of the statue J. Arrowsmith, eventually covered the cost. Arrowsmith belonged to a group of Bristol businessmen for whom Colston represented an idea of respectability and self-made wealth. He also represented an idea of rich paternalism which could be looked to as a bastion against the rise of socialism and private charities. The slavery on which his fortune was built was obscured for the purposes of a creating a certain narrative of Bristol's history and as a smokescreen behind which could be hidden the inequality that meant that Bristol, like so many cities in England at that time, was sharply divided between the haves and the have nots.

I have been looking at the continuing importance of ritual recently and the ritual commemoration, celebration and memorialisation of Edward Colston was crucial in the communication of a 19th century concept of Colston that legitimised capitalist individualism, both morally and economically, as a political system. Colston was also used as a symbol for the right of limited but sustained private relief organised and distributed by those considered the city’s moral and economic leaders, thus cementing the authority of the rich to not only determine who had money and who didn't but that the rich were in some way given almost divine status as 'benefactors' of their poor brethren. It was around this constructed symbol that the rich merchants at the time then constructed rituals similar to those we see in the masonic tradition, rituals designed to re-affirm their powerful position within the city. The ability to depict Colston as both ‘merchant prince’ and ‘moral saint’ was thus central to the perpetuation of 19th century capitalist ideals. If you want to read the details research the work of the Bristol Radical History Group.

So we have agendas within agendas. Many of the people protesting against the toppling of the statue stated that Bristol needs to retain its history and that times and therefore values change, but no one as far as I can remember, stated that the statue was erected to serve a particular purpose, in that it was designed to become the centre piece around which certain rituals could be developed and enacted, rituals that gave 'divine' authority to a group of rich white merchants and that the statue was a political construct erected long after the actual events of Colston's life and not a celebration of Colston's philanthropy by the common people of Bristol. The problem is that history is something we can all mine in order to support our own agendas.

It has also been quickly forgotten that soon after the toppling the artist Marc Quinn had erected a sculpture of activist Jen Reid to take the place of the slave trader's statue. Quinn had his statue secretly installed overnight on the plinth, an action that quite rightly drew the ire of virtually every political spectrum out there. Quinn had forgotten that the issue was all about power and who has the right to exercise it. By taking it upon himself to make a decision as to what sort of representation should stand on the plinth, he was exercising his own power as a well known artist, and as he is white, middle class and male, he was seen as providing yet another example of those with power, taking their power for granted. Quinn's action was paradoxically in many ways reminiscent of Arrowsmith's. Both men wanting to have statues erected that celebrated their own status, both men looking for a subject that could be read in terms that would by association celebrate themselves and their own agendas.

The exhibition of the rescued statue can only be attended if you book a timed visit with the museum. These sessions have it appears been block booked by those that want Colston's stature resurrected where it was before. They don't like the idea of the re-presentation and intend to stop anyone else experiencing it; so much for letting the people of Bristol access their own history. Instead of standing over 18 feet high, Colston is made to lie horizontally in such a way that people can get up close and examine the statue and its graffiti. The most powerful visual signifier being the red paint that covers the statue's face, which felt to myself as if the blood of the dead had come back to haunt him. So who's history are we to celebrate? Colston's, Arrowsmith's, the unknown graffiti artist's, the people of Bristol? The conservators have reported that the statue is structurally damaged, so it would require extensive repairs if it was to be returned to its plinth.

There is though another issue for us to consider, and that is how powerful body metaphors are. By simply taking something that was standing up and not just standing up but standing proud and re-presenting it in a lying or horizontal position the meaning has changed completely. At various times this blog has asked its readers to rethink how work is presented and it has also argued that a re-presentation can be more meaningful than the work itself. The arguments surrounding the Colston statue illustrate the point really well, we feel as if the fall of the statue and its post-fall recumbent position embodies a deep truth, that of an active youth being overtaken by old age and then death. That is the deep metaphor behind it all. One set of values are now becoming redundant and different values are taking their place. This is of course unsettling, especially if you see yourself as belonging to a group of people that still cling on to those old values.

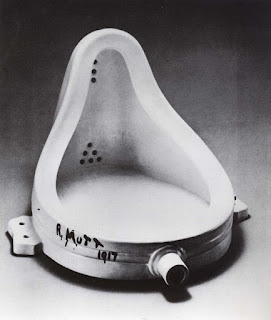

Communication theory suggests that we examine who communicates what to whom, in what channel and with what effect? When undertaking any form of analysis it is also suggested that you compare and contrast a similar situation that is different enough to allow you to illustrate salient points. So I have decided to look at how John Cassidy's Colston's statue of 1895 and Duchamp's 'Fountain' from 1917 have both been used to communicate ideas.

These objects were put on display only 22 years apart, but one was in Bristol and the other in New York. Both objects were cast, one in ceramic and the other in bronze, both objects were intended to make a point and both objects have been subjected to considerable changes in their perception over the years since their making.

John Cassidy's work was commissioned by a group of the great and the good of Bristol, this commission was part of a long term falsification of Colston's life, which included spiritual transformations and miracles such as rumours that samples of Colston’s hair and nails had been secretly conserved and were worshipped by the Society of Merchant Venturers in the Merchant's Hall, like medieval religious relics, and the ‘miracle’ of the Dolphin that saved one of Colston’s ships in a storm by plugging a hole in the hull with it’s body. The unpalatable aspects of Colston’s history, such as his leading role as an organiser and profiteer in the slave trade and his religious and political bigotry, were ignored and whitewashed away.

Duchamp's work is similarly surrounded by stories of falsification and begins its journey at the behest of a committee. The Society of Independent Artists was based on the Parisian Salon des Indépendants and Duchamp was a founding member. All submitted work to the society's exhibition was to be accepted and Duchamp tells a story that he submitted 'Fountain', a urinal signed R. Mutt as a test to see whether or not the rules were being adhered to. However there is another story. Glynn Thompson argues that all the evidence suggests that the urinal was the work of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. The urinal it is argued by Thompson and Spalding is in fact the world’s first great feminist, anti-war work of art. The art world has persistently refused to acknowledge this, especially because so many ideas and concepts that are central to the idea of contemporary art practice are focused on a post-Duchampian narrative.

Both works are externalised ideas, examples of the extended mind concept. Their physicality allows us to think about ideas in ways that allow for their appropriation through ritualisation. The statue of Colstan was used by Arrowsmith and other members of Bristol's civic and business elite as a symbol of civic pride, in particular a pride in business and individual achievement and in paying for the erection of a sculpture, it also demonstrated their good taste and the passing of that taste onto the people of Bristol. The fact that it is Andre Breton that begins to develop a new narrative for 'Fountain' in the 1930s shouldn't be forgotten. Breton was a member of another elite, the European art intelligencia and his idea that 'Fountain' was one of the earliest examples of a found object, fitted in neatly to his other ideas about mundane, mass-produced objects developing new resonances when arranged in unprecedented configurations. The surreal object is a very close relative to the found object. Both suggest that meaning is something that is very tenuous and that what was once an object anchored to a particular use value, such as being something to urinate into, can by changing its context become a nightmarish vision emerging from the subconscious mind or a piece of sculpture. The object in this case representing the clever ideas of a certain group of intellectuals who were seeking to validate their own positions within a newly developed art world.

In the same way that Colstan's role as a slave trader was forgotten, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's role was forgotten too, women were not yet ready to be taken seriously as artists by the art world.

No comments:

Post a Comment