There still seems to be a worry about the relationship between fine art drawing and illustration. I personally find no real difference between them, both are concerned with trying to represent and communicate visually things that we experience. The fine artist often makes very personal decisions as to what is being visualised and the illustrator is usually more directed by the role they have in solving problems set by others, but whether the problem set is a personal one or set by others, at the end of the day a piece of visual communication is made, that is either one that works well or doesn't. The history of art includes many artists working directly for clients, be these to do with the church, the ruling elites or galleries and many artists have also worked as illustrators or have had roles that didn't separate out the 'artist' from the other functions that someone was involved with. For instance a monk may have also been a fantastic image maker, but their main role as someone in the service of whatever religious order they belonged to, meant that they were never singled out as 'signature' artists; in fact most artists would as far as history is concerned, be anonymous. We can ask questions of an artwork, such as does the work enrich our understanding or awareness, does it help us to get more in touch with our feelings, does experience of it allow us to do things differently? But we can ask these questions of a fine art painting, sculpture or drawing, just as much as we can of an illustration,

I compare my own work with both fine art and illustration. For instance, my interest in interoception overlaps with medical illustration as it attempts to visualise what goes on within the body but I'm also trying to communicate feeling tone, something more akin to music perhaps and therefore closer to artists dealing with expressionist themes, so I'm also happy to look at artists such as Max Beckman or Cecily Brown, both of whom have contributed to the visualisation of the human body's expressive possibilities.

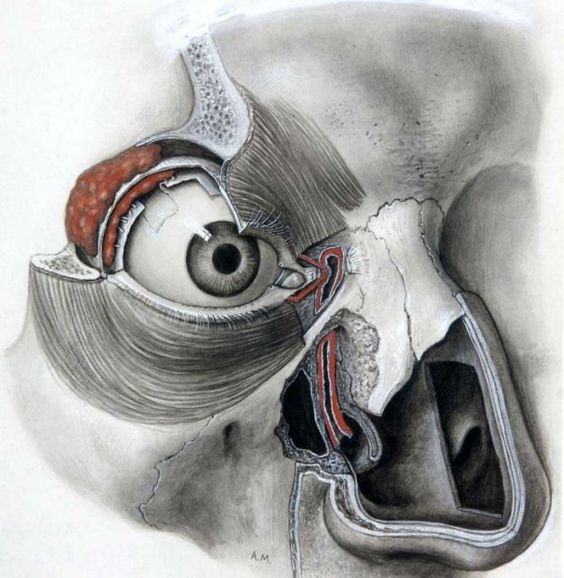

There is a history of medical illustration that is vitally important to how we think about the interior of our bodies. One artist in particular was very influential on the development of the contemporary anatomy textbook and his work is also of interest to myself in that he developed very specific techniques in order to communicate the particular qualities of our visceral insides. Max Brodel (1870-1941), is considered to be one of the shapers of modern medical illustration. He understood that a drawing was much better than a photograph when it came to showing others what was going on and he had this to say about copying:

"Copying a medical object is not medical illustrating. The camera copies as well, and often better, than the eye and hand, in medical drawing full comprehension must precede execution."

In order to better communicate what he was seeing, Brodel devised a method of using carbon dust to create a two tone technique that could capture the sparkling highlights that characterise the wet visceral look of the interior living body. His particular use of carbon dust involved using special paper coated with white layers of chalk or clay. Carbon dust is then layered on the paper in stages to create shadow and depth. The results are incredibly rich tonal images that not only suggest wet insides but capture the nature of three dimensional form well. He also used erasers to lift out bright highlights and create further three dimensional effects.

It is interesting to compare his drawings with Alberto Morroco. Alberto Morrocco unlike Max Brodel was an artist better known for his landscapes.

Reference

Cullen, Thomas A. "Max Brödel, 1870-1941, Director of the First Department of Art as Applied to Medicine in the World". Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. Vol. 33, No. 1, January 1945.

Macdonald. Joanne (2022) How can drawing support understanding in anatomy through the work of Robert Douglas Lockhart (1894-1987)? Aberdeen: Aberdeen UniversitySee also:

No comments:

Post a Comment