Her work in 'Strange Clay' inhabited an artificial landscape, as if creatures from a fairy tale were becoming 'real', whilst in another exhibitions she has used a cabinet to house her work and tables and chairs as surfaces for both display and interaction with her ceramic figures.

Thursday, 30 May 2024

Klara Kristalova: Ceramics and drawings

Her work in 'Strange Clay' inhabited an artificial landscape, as if creatures from a fairy tale were becoming 'real', whilst in another exhibitions she has used a cabinet to house her work and tables and chairs as surfaces for both display and interaction with her ceramic figures.

Thursday, 23 May 2024

John Craxton and Jake Grewal

I recently saw the John Craxton exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester and after spending some time with his work, moved on and found hosted within their more permanent collection some of Jake Grewal's charcoal drawings, that he had on exhibition alongside a few of his paintings. Craxton was born in 1922 and yet his work feels as if it still has resonance, especially when you put it alongside the work of an artist born in 1994.

Jake Grewal’s drawn landscapes include naked men, figures that you might need to spend time finding, as they are often hard to see clearly, because they are deeply set into the smoky grit of his charcoal marks. He is obviously influenced by British Neo-Romantic artists, such as Caxton and Keith Vaughan and often works outside, which is perhaps why the drawings feel as if they are still in touch with nature.

For myself it was the issue of how we can be in touch with nature that I was most interested in. Both Caxton and Grewal are gay and I had the feeling that they were both drawn to the idea that in a natural state, conventions such as a male/female cultural divide could disappear. In Craxton's case the human presence is amalgamated with and locked into the forms of landscape by his particular use of pen, ink and wash, whilst for Grewal it is the charcoal that allows him to bring his figures into the same world as his landscapes. This is the magic of materials and how they are worked. By placing an idea into a material form, that idea becomes materialised and in that very materialisation it transcends the human and becomes a thing. The human becomes an ink thing or a charcoal thing and in becoming these new forms, is released from the conventions that bind real people.

St George and the rather small dragon are really a pretext for the painting's real subject which is the magic of the wood and wonder of the lush but wild landscape. There is an arcane atmosphere whereby we understand that human deeds, even mythic actions such as Saint George overcoming the Dragon, are all subordinate to the power of nature.

Thursday, 16 May 2024

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood

I was in Bristol recently and went to see the Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood exhibition at the Arnolfini. It finishes on the 26th of May, so there is little time to get to see it, but still worth I think a review as it raises several issues that are still very pertinent to contemporary art practice.

The exhibition sets out to balance our view of how motherhood has been portrayed in art, the introduction to the exhibition stating;

'While the Madonna and Child is one of the great subjects of European art, we rarely see art about motherhood as a lived experience, in all its complexity. Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood will address this blind spot in art history, asserting the artist mother as an important – if rarely visible – cultural figure'. Featuring the work of more than sixty modern and contemporary artists, this exhibition will approach motherhood as a creative enterprise, albeit one at times tempered by ambivalence, exhaustion or grief. Acts of Creation will explore lived experience of motherhood, offering a complex account that engages with contemporary concerns about gender, caregiving and reproductive rights. The exhibition will address diverse experiences of motherhood across three themes: Creation, which looks at conception, pregnancy, birth and nursing; Maintenance which explores motherhood and caregiving in the day-to-day; and Loss, which touches on miscarriage and involuntary childlessness, as well as reproductive rights. The heart of the exhibition is a series of revelatory self-portraits – a celebration of the artist as mother.

I went to the exhibition with my partner and one of our daughters, so it was interesting to get their opinions as well as my own drawing focused reflections.

"Has it taken all these years?" was my partner's comment, as she had worked with several of the artists on exhibition back in the 1980s and was remembering how few galleries at the time, except for the ICA, would show this type of work. A necessary rebalancing I therefore thought, but her point was that it is now all too safe and easy to show work of this sort after the event.

My focus, as usual with most exhibitions I travel to, was on the artists who use drawing. This blog is supposed to be about contemporary drawing and I have perhaps stretched the definition at times, but it still seems to make sense to have this particular focus, if for no other reason that my own art practice is drawing led.

I have put an image by Claudette Johnson at the top of this post, mainly because she is able to transcend what could be an old and tired genre, 'the life model', and turn it back into what it should always be about, an honest confrontation with a naked, human being. The drawing 'Afterbirth' is a straightforward drawing, using pastel to communicate the softness, but also strength of a woman's body. She is proud of what she has achieved and looks us directly in the face and makes no apologies for presenting herself 'afterbirth'. I really liked this drawing, as it seemed to me to involve very little artifice, 'what you see is what you get' and what you get is a mature woman, who is happy to be in her own skin and who makes us aware that she takes her space comfortably.

It is hard to escape history. The most famous image of mothers and their children in the National Gallery in London, being Leonardo's 'The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist'. The two women appear to be very close, physically and mentally, forming a collective mass, out of which emerge the children. It suggests to me the solidarity women feel in their collective motherhood and like Claudette Johnson's portrait, these women have a gravitas and weight that gives them an authenticity. I feel that Leonardo witnessed this, or at least a significant element of the composition, and this is why it feels so 'in the now' and not a dead fragment from the archives.

See also:

Documentation and drawing practices

Wednesday, 8 May 2024

Collaboration and copying

A Braarudosphaera bigelowii cell, with a black arrow showing its nitrogen-fixing organelle

Tyler Coale, University of California, Santa Cruz

Two of the strands that this blog tries to weave in and out of its fabric are collaboration and copying. Sometimes as a way to develop new drawing ideas in responses to experiences in collaboration with another artist, and at other times as a reminder that we cant really exist without operating in collaboration with the environment that surrounds us. Our very existence depends on collaboration. Not only our day to day survival in relation to a symbiological relationship with the world around us, but in a deep sense, related to the way that life itself has evolved and how it reproduces. I was reminded of this when I read recently that a bacterium that used to exist on its own has evolved into a new cellular structure that provides nitrogen to algal cells. At a cellular level it is quite common for one species of bacteria to live inside the cells of another species. I have mentioned before that humans could be thought of as hosts for bacteria, as there can be more body mass attributed to them, as opposed to what you might call us. This is a situation that exists throughout the natural world, for instance, cells in the roots of peas host nitrogen-fixing bacteria, and cockroaches host endosymbiotic bacteria that provide them with essential nutrients.

The evolutionary history of these collaborations can be explained using endosymbiotic theory or symbiogenesis, a theory that argues that bacteria began living in eukaryotic organisms after being engulfed by them, indeed the two major types of sub-cellular structures found in eukaryotic cells, (cells with a membrane-bound nucleus) are mitochondria and plastids, both of which evolved from bacterial endosymbionts. As all animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes, this places symbiogenesis at the root of life's evolutionary history.The fact that new mitochondria and plastids are formed only by splitting in two, supports the idea that it was in the coming together of different elements that basic life forms were created. This splitting is called fission and it is interesting to think how this is done and how the concept of copying lies firmly at the core of how life survives in the forms that it does.

Stage 1: The bacterium before binary fission has the DNA tightly coiled. Stage 2: The DNA of the bacterium begins to uncoil and has replicated. Stage 3: The DNA is pulled to the separate poles of the bacterium as it increases size to prepare for splitting. Stage 4: The growth of a new cell wall begins the separation of the bacterium. Stage 5: The new cell wall fully develops, resulting in the complete split of the bacterium. Stage 6: The new daughter cells have tightly coiled up their DNA.

The complexity now associated with these processes has evolved over millions of years and this evolution has determined that cells work in amazingly sophisticated ways within our bodies. Indeed there are what are called somatic-junctions, where cellular quality control is developed, as signals are passed between cells in order to develop bodily responses to the changes that it experiences as it passes through life.

Wednesday, 1 May 2024

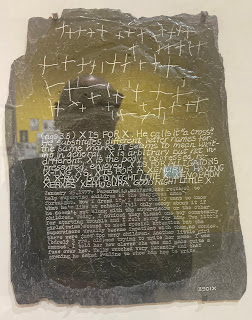

William Blake at the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge

William Blake’s Universe at the Fitzwilliam Museum Cambridge is a wonderful exhibition, so good that I had to spend two days in Cambridge, so that I could go back and look twice. The quality and range of the images is extraordinary and it is not just Blake's work that you need to see. For instance there are images by Casper David Friedrich, that reminded me that it is possible to create landscapes that glow with mystic spirituality, such as 'Sea at sunrise', images that need to be seen in the flesh if you really want to get an idea of their intensity. The issue about 'Sea at sunrise' being that the image is stripped down to almost nothing, except the play of light as it vibrates through the air and dances on water. Light of course in Friedrich's case, being a metaphor for the constant presence of God, but for myself a reminder that the Sun is the shaper of all life on Earth, and that life originated in the sun energy charged chemical soup that we call the sea.

I was also fascinated by the diagrammatic work of Jakob Böhme. Some of the plates illustrating his ideas were printed onto layers, so that flaps could be lifted and you could see underneath.

As well as being introduced to some things I hadn't come across before, perhaps it was the 'intensity' of people's visions that I was most impressed with in this exhibition, all of the works and artists represented, managed to communicate a total commitment to some sort of psychic command of visual language. Blake is of course the most well known of the artists in England and his influence on Samuel Palmer, who is also represented in this exhibition, was clear to see, but it is the chance to see a collection of Blake's images, exhibited in sequences that has the most powerful effect. I was soon wondering, because of the sequential nature of his art, how he would have responded to the comic book tradition, would he have been a sort of mystic Robert Crumb?

Thoughts of this type still emerge from my brain, as it was shaped like so many children of the 1950s by having to go to Sunday School for most of our formative years. Therefore the Bible, whether or not we eventually decided to be atheists, would loom large in our creative imaginations. No matter how hard I try to intellectually move beyond notions such as 'good' and 'evil', an all seeing God and a Saviour who died for us all, my neurological wiring from those experiences, is still in place.