There have been several schools of British

Drawing and each one has developed a different focus. However two in particular

have interested me and both continue to have a lasting influence when I look at

how to approach drawing from life.

The first but perhaps least important to me is

the Slade School of drawing as practiced by William Coldstream and brought to a

sort of head by Euan Uglow. Uglow in particular demonstrated that the process

of looking needed to be one of total focus and that you needed to be fully

aware of yourself and your position in relation to the subject if you were to

understand what was happening. Coldstream used small dots and

lines to define points of measurement and Uglow took these things on as almost

stylistic devices.

Coldstream drawing: His measurement grids helped to locate relationships between objects

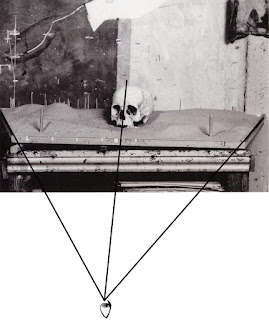

Look at the peach below, Uglow attempts to ‘trap’ it within

his pins of measurement.

However it was when I first saw images of Uglow’s studio

that I began to take him seriously.

Uglow's studio set-ups show how obsessive he was and how determined to control vision.

David Bomberg had a very different approach one

he taught for several years at the Borough Polytechnic, his legacy is

remembered by a residency, which one of you could apply for at some point.

Bomberg had at one point studied under Walter

Richard Sickert, Sickert’s paintings of everyday urban life suggested the

material fact of the city was carried by the physical fact of the paint. (There

was also a myth going round at the time that Sickert was really Jack the Ripper

and a strange confliction between the artist’s gaze and the killer’s knife came

into life room conversations).

A Bomberg drawing of London

Bomberg’s late works are constructed by vigorous

brushmarks, and have a powerful grasp of the physical energy of seeing. His marks did not just record physical appearance but were an embodiment of

his almost tactile understanding of the nature of perception. Bomberg’s key

phrase that he used to describe this process was a search for “the spirit in

the mass”.

Bomberg: Self portrait

Several of Bomberg’s students went on to have successful careers of their own, the most well known being Dennis Creffield, Leon Kossoff, Gustav Metzger, Roy Oxlade and Frank Auerbach.

Leon Kossoff

Frank Auerbach

Roy Oxlade

Dennis Creffield

Bomberg believed that

looking was about action and therefore centred on movement. Touch he believed

was central to our understanding of visual perceptions and only in movement can

we experience what is actually in front of us.

One of Bomberg’s ex-pupils Miles Richmond in the

introduction to a painting exhibition in 2001 stated, “Painting matters to me since I know

no better means of exploring the connections between our outer and inner worlds

and presenting evidence of that exploration’. Drawing and painting were seen by

Bomberg and many of his pupils as a type of exploration of experience and that

experience was as much to do with a set of inner emotions and sensations as with a direct physical engagement with perception. In fact direct perception of

the world he would argue is impossible, it is always mediated through our

mental map of who and what we are.

Cliff Holden another ex-student of Bomberg pointed out that

Bomberg believed that children only learn to see through the testing of

experiences via movement and the sense of touch. He states, “Movement

gives a sense of space and distance. You cannot see distance – you can only

measure it”.

Holden goes on to state that Jacob

Bronowsky when describing the drawing of a face noted that “the picture does

not so much fix the face as explore it ... that the artist is working almost as

if by touch and that each line that is added strengthens the picture but never

makes it final.”

These

issues have been with us for some time. Bernhard Berenson in his great book on

the Italian Painters of the Renaissance pointed to what he called “space-composition” as being a far more

advanced way of organising images than two dimensional arrangements, which “extend only side to side, or up and down on a flat surface.”

Berenson points out that the most advanced painters of the Renaissance developed

spaces that extended inwards. Space-composition, he believed, heightens our

consciousness of being alive. This type of understanding also relates to what

is called ’somatic

theory’ or critical thinking as an embodied performance. See Merleau-Ponty’s

essay Cezanne's Doubt which was an early attempt to write about these issues.

Essentially the world around us is

not static and neither are we, we are in effect dancing with our perceptions

and constructing meaning as we see and as we think and as we do.

Therefore

it is only through movement that we can truly assess what form in a drawing is.

The ‘idea’ of form as well as its re-creation can only therefore be found

through the actual activity of drawing or painting. Trying to work towards a

preconceived image, would in effect be to ‘kill-off’ the experience rather than

re-create it.

This

is why we in the last few life sessions have moved from static measurement

towards a more embodied perceptual approach to looking, the curve of vision,

being just one aspect of the continuous flicker of the eyes as they scan the

world and seek out meaning. As the evening sessions continue we will work more

and more towards the discovery of form through making.

Bomberg

did not have any answers as to how you should make an image look, simply that

as artists you should be open to the experience of the situation. The “spirit

in the mass” essentially being a reminder that if solid form was to be found it

would only be found within an embodied performance. Each mark made by the

artist being a sign, signs that collectively begin to steer the eyes towards a

new understanding of what it is to experience mass and space within the world. In

many ways this is an impossible situation, drawings and painting are in reality

simply marks on flat surfaces. However the faith that artists such as Bomberg

had in the ability of images to contain these complex ideas about life and

perception was for me far more life affirming than Greenberg’s insistence on

painting’s specificity.

For

more information on issues related to the teaching of drawing and perception

see these other blog posts

For a simple animated

introduction to Greenberg See this playful intro that uses drawing in a very basic but informative way, one that after all the looking and measuring might be exactly the right one to carry your other message.

No comments:

Post a Comment