The nearest phenomenological experience I suspect I ever encounter in relation to auras is when I get a migraine. An initial shift at the edge of my vision begins to splinter into the colours of the spectrum, and then gradually the world I look at begins to bend and fragment, the experience being not unlike looking at the world through a cut glass vase. I sense that if I could see myself from outside my body, my head would be surrounded with a faceted glow. I have had these migraines for many years and when I get them I just accept them and watch. They are a useful reminder of how much the world is a construction of my perceptual system and I try to hold on to the sensation of moving through what becomes a very fragmented world, even though I am intellectually aware that nothing outside of myself has actually changed.

I found this image of a Roman Sol Invictus recently and I felt that perhaps its maker had also experienced migraines. I liked the fact that the eyes were shut, suggesting a concentration on internal energies, that were then escaping through the head. A glow around the head is a visual idea that in religion is usually called a halo and I think that because of the prevalence of so many halo type glows that emerge from Holy Ghosts, Jesus and the Saints, that a heavily Christianised society such as that in 19th Century Britain, would have been well prepared for an idea of invisible auras, so it is no surprise to see texts such as 'The Chakras' by Leadbeater, whereby he illustrates chakra forms as if they are circular auras, or 'Man and His Bodies' by Annie Besant, which has a chapter on 'the human aura'.

I had earlier played around with Plutchik's idea and had placed colours around his cone of emotions, as I did like the fact that different saturations and tonalities could be linked to degrees of emotional intensity.

Whilst religious iconography picked up on the visual power of aura type images to represent invisible mystic or divine powers, our bodies can also be thought to hold within them other types of invisible energies; energies that could perhaps be visualised in similar ways. For instance, the heart's rhythmic contractions create a strong magnetic field that can be detected outside the body using magnetometers and it has been observed that this field can be modulated by emotions. As someone with atrial fibrillation, I'm very aware of how when my heart speeds up in response to an emotional dilemma, my interoceptual awareness of it changes and I can 'feel/see' these energies moving through my body.

Dermatomes of the Upper and Lower LimbsIt is not so much whether or not there can be any scientific proof of auras, what I'm looking for is how we are predisposed to think visually about them and what they represent. In my work looking at the visualisation of interoception, what I often find myself doing is sitting with someone whilst they describe to me an inner feeling, be this pain, emotion or another sensation and the ground out of which the conversation emerges, must not be that dissimilar to the landscape out of which thinkers such as Kilner emerged. I listened recently to a podcast devoted to synaesthesia and one of the people talking about their experiences had emotionally mediated synaesthesia, which meant that she saw colours surrounding people and these colours changed, often due to her emotional connection with the person seen. As she went on to describe, what was for her an everyday experience, I began thinking about how perhaps it was those of us who literally see differently, that help us as a species come to see or visualise those things that most people cant see, such as emotions. For instance we mainly have a three colour visualisation system called trichromacy, but evidence exists that there are people who have four distinct colour perception channels or tetrachromacy. Apparently it’s more common in women than in men and it has been suggested that nearly 12 percent of women may have this fourth colour perception channel. Is this why it is often suggested that women are more 'psychic' than men?

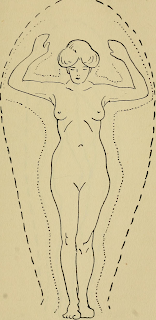

However, back to Kilner. He created what came to be called 'Kilner screens'; which were treated with variously coloured liquid dyes. These screens it was argued allowed us to see outside the visual light spectrum, and what could be seen were the result of seeing 'N-rays'. 'X-rays' immediately come to mind here. In his book we read that his screen allows us to perceive various auric formations, such as the 'Etheric Double', the 'Inner Aura' and the 'Outer Aura', which were formations that extended several inches from patients' naked bodies. His screens were more popularly known as Kilner goggles and are in my mind very closely associated with 'x-ray specs'.

However there are far more prosaic forms of invisible energies passing through the body.

The engraving above is really about sweat. The "insensible perspiration that issues from the pores of the body, which can only be discerned by means of a lens and that ascends through the bed-clothes like a mist when we are asleep", is I'm pretty sure, sweat. But we are all very aware of what happens when we have a fever and it is another invisible something passing through the body that we need to reckon with.

Once again an idea seems impelled into being by a psychological need and I sense that Burr's book might be as much to do with art as science. However time to end another ramble, especially as I have just discovered after writing most of this post that there already exists a book, 'Picturing Aura' by Jeremy Stolow, that seems to cover most of the ground I've been thinking about.

Coda

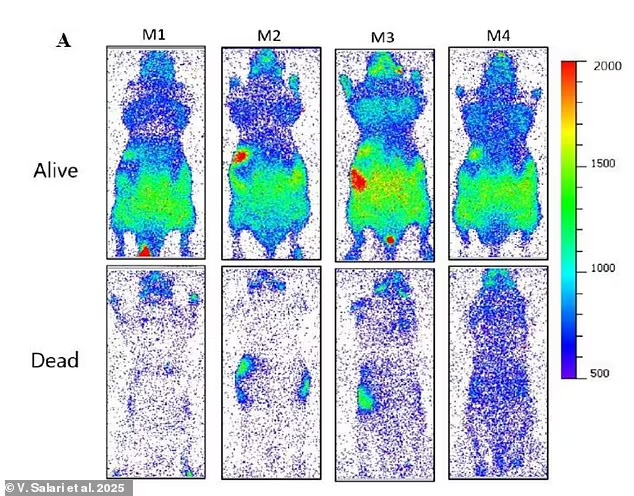

The full explanation was; 'One thing that all living creatures have in common is that they need to create energy to stay alive. In the cells of every organism, there are structures called mitochondria where sugars are 'burned' with oxygen in a process called 'oxidative metabolism'. During these reactions, molecules gain and lose energy, letting off a few photons...Because the light emitted by living cells is so faint, it is hard to distinguish from other natural sources of light, such as the radiation emitted by warm objects. However, using specialised cameras able to detect individual photons, Dr Oblak and his colleagues have now isolated this light and shown what happens to it after an animal dies'.

Mice were placed in dark, temperature-controlled boxes where digital cameras produced two images with an hour-long exposure. One was taken while the mouse was alive, and the other after it had died.

Perhaps those individuals that have more rods or cones than is normal, (in effect mutants with tetrachromacy); can detect these photons and this could be yet another explanation for the aura concept.

ReferencesFenici, R. Brisinda, D. and Meloni, A.M. (2005) Clinical application of magnetocardiography. Expert review of molecular diagnostics, 5(3), pp.291-313.

Kilner, W.J., (1911) The Human atmosphere, or, The aura made visible by the aid of chemical screens. Rebman Company. Available at: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/t94es3zc/items

Ramachandran, V.S., Miller, L., Livingstone, M.S. and Brang, D., (2012) Colored halos around faces and emotion-evoked colors: a new form of synesthesia. Neurocase, 18(4), pp.352-358.

Renbourn, E.T., (1960) The natural history of insensible perspiration: a forgotten doctrine of health and disease. Medical History, 4(2), pp.135-152.

Salari, V. Seshan, V. Frankle, L. England, D. Simon, C. and Oblak, D. (2025) Imaging Ultraweak Photon Emission from Living and Dead Mice and from Plants under Stress The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 16 (17), 4354-4362 DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.4c03546

Stolow, J. (2025) Picturing Aura London: MIT Press

See also:

Diagrams: Visualising the invisible

Interoceptual textures and surface flow

Para-scientific visions and Rayonism

The iconography of the invisible

.%20c1788.%20Courtesy%20the%20Wellcome%20Collection.png)