Staffordshire spill vase

Spills were still used to transfer flames and help light fires when I was a boy, and I like to still make 'spill vases' using the Staffordshire form, not that they have any practical use any more, but they remind me of how time moves on and of how outdated forms gradually acquire new meanings. Working in the way I do is also 'old fashioned' but then again anyone over 70 is indeed 'old fashioned', my ideas partly a product of my 1950s upbringing.

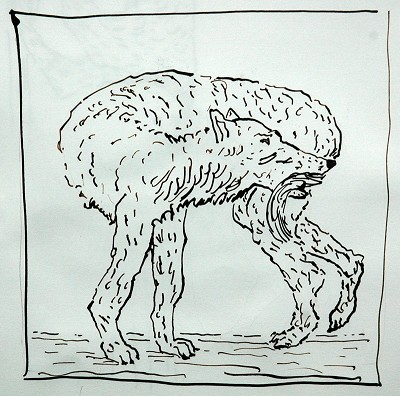

The monkey belongs to grandad Freeman, my mother's father. He used to tell me stories of his time in India, where he was posted during the First World War. His pet monkey was obviously of great comfort to him when posted far away from home, in a very foreign environment. He must have tailored his stories for a young boy, because in my mind grandad's monkey was a sort of simian Black Bob; a clever aid to my grandad, who would get involved in all sorts of adventures, as grandad negotiated Indian life. He never mentioned any fighting, but lots of stories about getting food, whereby his monkey would steal fruit or entertain others while grandad managed to help himself to what he wanted. He told me his monkey was a good listener, who would come into his tent at night and share food, whilst grandad told it all about life in England and it told him all about life in India. His monkey was cheeky and would annoy officers by making rude gestures and stealing things from them, or so grandad said. Back in the 1950s somewhere in Pensnett there used to be a pub that kept monkeys in a cage, I cant place it on a map; but in my memory we walked quite a long way to get there, through rough ground and fields. We only went in summer, grandad and I; we would go out together walking and talking about life, the universe and everything. When we got to the pub we would get a seat at an outside table near to the monkey cage and grandad would retell his monkey stories, pointing out differences between his semi-wild cheeky pet and these locked up, sad specimens. He was obviously not allowed to bring his monkey back home to Pensnett, and it must have been a difficult moment of separation for him, but the monkey lived on in his mind, as a powerful spirit that held on to grandad's wartime experiences. That monkey is still cheeky, still anti-authoritarian and it loves to be included in stories.

Drawing for monkey spill vase

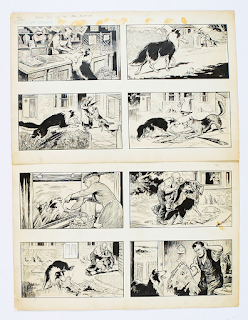

Because my surname is Barker, I've had a long time association with dogs. My nickname at school was 'hylax', the latin for a barking dog, which in turn was derived from the Greek word hylax (ὑλάκτης), meaning "barker" or "watchdog". I liked the idea that as an artist I could operate as a watchdog. But as I'm also prone to be my own worst enemy, and end up going in circles, I was also a dog that bites its own tail.

The dog is also a fusion of two real dogs, Scamp and Sam. Scamp was my boyhood dog who went with me as I played within the pitted post-war landscapes of Himley Road in Dudley. From the smoking underground fires of Russell's Hall, via the slag heaps that formed the background landscape to where we lived, Scamp would be with me. Sometimes he would get covered in grey clay as we played in a local stream and I would get a spanking and real telling off for getting him so dirty and at other times he was my saviour, barking at boys who wanted to fight me. Scamp was my Black Bob; we had all sorts of in my mind adventures, as we wondered the scarred landscape of bomb craters and burnt out factories. We were together reliving cowboy and Indian stories, tales of ancient Arthurian England and the New Adventures of Flash Gordon. Sam was the dog we had when the children were young. My daughter was for a while a keen horse rider, and so we would on a weekend walk to the stables, and while she was there I would take Sam out past the ring road, following Meanwood Beck. In such a quiet place I could walk with Sam off the lead, she would paddle in the stream and run around, chasing after any sticks thrown, giddy with excitement. I would be lost in my own world, imagining things, constructing worlds in my mind as we walked, happy in my own company. Sam kept me sane during those years when I would sometimes lose all track of what I was supposed to be doing.

Black Bob

The rabbit belongs to someone outside of the family, and yet it is also Br'er Rabbit, the stories of whom, retold by Enid Blyton, I read to the children many times.

The rabbit was also a creature from a story told to me by a migrant who had crossed the Mediterranean Sea. Whenever danger threatened he would look out into the swell surrounding the boat and if he could spot his rabbit swimming beneath the surface of the water all would be well. The rabbit was a sort of invisible/visible angel that accompanied the man on dangerous journeys, a spirit form that could morph into its surroundings and which took care of the man and protected him from harm.

Horses are forever associated with my grandmother. She could talk to them. When she was a girl her parents lived above the steelwork's stables, where her father worked as a groom. Before motorised transport horses were the only way to move around heavy materials and metal is very heavy. The horses had to be kept healthy and my gran used to often sleep with them when she was a girl, and would be expected to alert her father to any issues that might be arising, such as if any horse had a fever or cold. She used to take me to visit the local blacksmiths in Pensnett and would talk to a horse while it was being shod, keeping it calm and reassured. Sometimes a horse would be tethered on a scrap of local wasteland and gran would go over and talk to it. She ran her fingers through its ears as she did and scratched its head and neck, I don't know what she said or what the horse replied, but their heads would touch and I knew something special was going on between them, nan sometimes breathing out heavily right up their noses. They were like relatives to her, all part of her mystery, an extension of her tealeaf reading powers and activities as the village healer. Horses are for myself because of my gran's activities, almost human, often morphing between states, they are the warning voice of the animal kingdom, too big to be controlled by us and only allowing us to ride them after a proper negotiation.

I have one image in my mind of a horse I will never forget; one day my wife Pam and myself were out for a walk with Ruth and William. Of the two children, Ruth always loved to engage with animals, no matter how big or small. We eventually came across a field with horses in it and Ruth wanted to feed one of them with a handful of grass. All seemed fine, until the horse dipped its head over the fence and grabbed hold of the hood of Ruth's coat with its teeth and hauled her up into the air, as if she was a bag of oats. For one horrid moment we thought we had lost her, but I was able to grab her back from whatever fate the horse had decided for her. It was a reminder of how powerful horses are and that if they wanted to, they could easily overpower any human. Nature has a dangerous edge and we forget that, being surrounded by the safety of cities.

The pig is often cruel or indifferent, able to read books and disengage when life around it is tragic, as in the drawing below. It is also an animal that has suffered greatly in the hands of human beings, an animal that waits its turn in the pecking order, as foreseen by George Orwell.

The pig was an animal that people still kept in back garden stys in the Black Country when I was growing up in the 1950s. At the time they felt like huge, primeval beasts and I was often sent to feed them left-over food scraps, such as potato skin peelings, every time being terrified that they would somehow get out of their enclosures and eat me. There were many tales told to me by adults of their cunning and ferocity, probably to stop me getting too close to them, but you knew as soon as you were next them and they looked at you, how intelligent they were and of how they could totally destroy you if they ever had the chance.

My primary school entrance was directly opposite to the local abattoir and I knew a boy who's father worked there, so we would often go inside, mainly to use the big floor sinks to play in, as they were places you could sail a boat in and have adventures. Surrounding us were lines of hanging dead pigs. We heard them from the playground when they were driven in for killing, they often squealed as they were dispatched, but we never really thought about what was happening; it was death on our doorstep, but so familiar that the enormity didn't really register until years later, when I began having dreams of standing in those sinks full of blood.

I have many versions of these animals in my head, some of which exist as puppets and others as characters in drawings or they take part in small ceramic scenes. The puppets are probably closest to how they appear in my head.

It is though the tranculments that it would seem people engage with most easily. When I make a 'tranclement' I hope that someone will put it on their mantlepiece or wherever else in their house they need a little story, my simple contribution to their lives.

The dog finally catches the rabbit: A tranculment in place in a home

Spill vases on a mantlepiece

Tranclements

These animals have allowed me to tell stories, much like the animals in Aesop's Fables, but I never wanted them to teach any moral lessons, they are creatures of my dreams, having material lives of their own, becoming another form for my externalised mind; brothers and sisters of Sooty, the frog, teddy and that stuffed octopus I used to sleep with seventy years ago.

See also:

Arvak A fable

No comments:

Post a Comment