Roy Lichtenstein: 'Knock Knock'

The new South London Gallery fire station extension has opened with the 'Knock Knock' exhibition, which stretches across both the old and new gallery spaces. The gallery is just off Peckham High Street, very close to Camberwell School of Art. Called after Roy Lichtenstein's 'Knock Knock' image, which is also in the exhibition, it asks us to consider the various ways that humour can be used within contemporary art practices. Drawing is very central to many of the artists' concerns, not least of course in the 'Knock Knock' image itself, an image taken from an original cartoon drawing. The 'knock, knock' joke is probably one of the earliest we learn as children, but when you begin to think about it, several, at times disturbing issues begin to emerge. Who is behind the door? In this case they have a very loud knock. The letters emerging from the schematic door suggest that whoever is knocking could be pretty powerful. The sound being in many ways more substantial than the door itself, the forms of letters made to suggest sound themselves being a sub-set of symbolic form. We have come across this idea before. See Christian Marclay's work in this earlier post. The humour now becoming 'funny peculiar' as we begin to think about how odd it is to see sounds visualised, and to consider why comic book languages have been the main area of visual thinking to investigate the possibility of visualising sound in some depth. (See Scott McCloud's thoughts on this) Visual images are usually thought of as being windows through which we can see 'picturesque' views. What is behind the picture or the illusion, is rarely considered. Jasper Johns occasionally nods in this direction, but he never really gets to grip with the full implication of what behind the image could really be about. What is behind the wall, or membrane is a very very old thing, one that goes back to pre-historic times. See

Jasper Johns

That old joker Marcel Duchamp was of course very 'tongue in cheek' in the way he operated, best of all his images in terms of drawing and humour being, 'With my tongue in my cheek'. A late image by the arch trickster, one that is suggestive of a fragment of a death mask, Duchamp's gaunt face captured in the cast of his cheek, a slight pencil line then filling in the rest. It doesn't feel like an image to make you laugh out loud, more an old man's ironic gesture towards what he has possibly achieved. Johns' use of Duchamp's silhouette, which often pops up in his work, is an acknowledgement of Duchamp's influence on Johns' thinking, the joke being perhaps from another perspective, that Duchamp did not actually make the strategic art moves that we all are taught to think he did. The space or absence in Johns silhouette drawing of Duchamp's head could then be read as a negative or point to a more vacuous influence. (See Glyn Thompson on Duchamp and his rereading of the man and his actions)

Duchamp: 'With my tongue in my cheek'

But back to the exhibition, and the role drawing plays in several of the exhibits.

Ceal Floyer

The fact that as soon as you look closely at the saw blade you can see that it is held up by a transparent plastic bracket, is sort of funny, but only in a what a pity this one liner isn't better way. The fact that this one line is a one liner, might be the joke, but it is a bit of a thin one. As you can perhaps see, one of the problems with art that is meant to be funny or humorous, is that it often just isn't. It's better if it's unintentionally funny. This image below is one of my favourite unintentionally funny paintings, one that I suspect does not go on tour very often. I think it is in the Petit Palais in Paris, but the achingly awkward pomposity of the aristocratic pandering that Ingres is twisting these bodies into goes right into my funny bone. In great power lies great potential for laughter, witness Trump's recent excursion into the United Nations.

Ingres: Death of Leonardo da Vinci

But humour is an essential part of the human condition so we must address it in some way and shows such as 'Knock, Knock' are important, because they ask us to stop for a little while and assess how even little one liners or daft moments help relieve the constant pressure of having to take the world seriously.

Cartoons, or 'toons' as they are often called, have a long association with humour. They are meant to be funny, but as I pointed out in the last post, Disney is just as much a part of the military-industrial complex as the armaments industry and the presence of Disney in so many of our childhoods means that we often return to these images when trying to work out what has happened to the world. Paul McCarthy's drawings in his series of commentaries on Snow White, juxtaposed different types of representation that could then operate on several levels at the same time. In McCarthy's drawings, the smooth cartoon language of Disney was set off alongside the scrawled language of sexual graffiti. Large drawings change our relationship with what is depicted and the monumental drawings of Disney characters by Joyce Pensato create a series of figures of a not dissimilar scale to the ones around the Parthenon.

A drawing of the figures taken from the Parthenon and now in the British Museum

Joyce Pensato: Take me to your leader

Pensato's drawing was of a parade of figures, parades were often at the centre of grand historical paintings. The tradition of historical painting being the most important was a vital part of the various art academys' teachings going right back to 1582, when the first academy was founded by the Carracci brothers. These huge charcoal and coloured chalk drawings also reminded me of those other cartoon drawings, which were done to transfer drawings on to walls so that fresco painters could be guided as to where each block of colour went. When I was 13 I went on a school trip to Rome and saw Raphael's 'School of Athens' on the walls of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. I was stunned, it was one of those moments that you know that your life I changing. Here was an image from hundreds of years ago that was talking history and philosophy to me now. It made sense of my idea that I might want to be an artist. I began to take an interest in how these things were done and discovered that they were part of a process, one element of which was making studies, then combining them to construct a composed image that could then be used as a template for transferring images onto walls.

Raphael cartoon for the 'School of Athens'

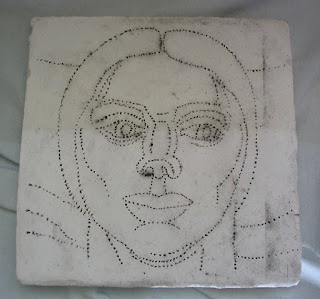

A pricked cartoon drawing that was used to transfer an image to wet plaster

If you look closely at Renaissance cartoon drawings you will always see either small holes or slits in the drawing where charcoal dust was pushed through so that it settled on the wet plaster beneath. For an artist the production of the cartoon drawing meant that they were ready to work full scale into the architectural space that their work had been designed for and they had been through the process of simplification and clarification that we now appreciate as being a hallmark of Italian Renaissance art, often forgetting that so many of the decisions were made because only a certain amount of wet plaster could be worked on at a time. Too much and the plaster would be dry and the paint would not combine with the wet calcium hydroxide to become an integral part of the wall as calcium carbonate. But don't these pricked drawings look just like children's dot to dot drawings?

The cartoon like sheep heads drawn on blocks of concrete by Judith Hopf were to be found collected underneath a stairway. Their legs are obviously taken from items of furniture like small tables, reminding us that in many ways furniture has an animal like presence. We have our own bi-lateral symmetry, and when we make things we tend to mirror that and give names like arms and legs to the extremities of the things we make. A chair has arms, a table has legs, we anthropomorphise the furniture that surrounds us. Animism is a very old form of religion and I think it is still with us; so for me, these sketchy sheep, and their unstable legs have a history that asks questions of their very unstable nature. Domesticated animals such as dogs, cats, sheep, goats, horses, chickens, cows and pigs have of course been part of our lives since time immemorial, now mainly associated with children's toys, we are far less aware of their presence now that we all live in cities; but the ubiquitous

presence of MacDonalds reminds us that we still eat them and we still need them for their skins and their companionship. Beneath the jokey presentation, once again we have layers of other possible meanings. The best thing about this work though was for me the insertion of small wedges under the legs. We have all had those wobbly table moments and there is always someone prepared to fold those beer mats or look for a handy wedge to save the day and sometimes artworks just need that wedge moment to conclude them.

Judith Hopf

Hardeep Pandhal is someone I have posted about before, his wall drawings and cut-outs are designed to remind us of his scrambled heritage and as I pointed out earlier his cartoon style can be traced back to both the Beano and Viz. My own reaction this time was one triggered more by the back views of his cutouts than by the front images, perhaps because I have looked at and thought about his work before and wanted another way into thinking about it. The pink metal stands that held up his images reminded me of Modern art, especially Caro's painted sculptures from the 1960s. Hiding behind Hardeep's cartoon figures is a pink formalist construct and does he realise that?

The snake text reads, 'Gagged by English'

Hardeep Pandhal

Hardeep Pandhal: Back view

Caro

Painted directly on one of the walls over in the new Fire Station extension was a 6 image block of cartoon drawings by Suds McKenna that directly referenced the abstract forms of Modernism. You could imagine the shapes in the Caro sculpture being rearranged to make a 3D version.

Suds McKenna

Van Doesburg

Picasso

McKenna has created a cartoon that looks as if it has been through a fusion of the formal shaping principles of artists such as Van Doesburg and Picasso, a process reminding us that not long ago cartoons were seen as the province of children and that only adults with childish minds would read them and that as far as many people were concerned this could apply to abstract artists as well.

Dot to dot drawings are another children's distraction, however the dot to dot apple below doesn't really need the dots joining, because we can see what it would look like, it is not complex enough. The dots become redundant. The image is more about an idea of dot to dot than an actual usable dot to dot drawing.

Andy Warhol's Micky Mouse for kids

Of course the commercial world has realised the potential for this type of thinking, the image above beautifully fuses these strands of thought together.

What would happen if we tried to develop a Picasso dot to dot drawing? A simple transformation of his drawing above already looks as if it could become a wrought iron gate for a Picasso museum.

Below is a close up of a Mona Lisa dot to dot puzzle.

Detail of a Mona Lisa puzzle picture

There is something crazy about the territory we are now entering reminiscent of Georges Perec's novel, 'Life a user's manual'. In the book, Bartlebooth, the central character, at one point tours the world and paints a watercolour view of a different port roughly every two weeks until he has painted 500 watercolours.

He sends each painting back to France, where the paper is glued to a support board and cut into a jigsaw puzzle. On returning from his travels Bartlebooth spends his time solving each jigsaw in order to re-create his experiences. Then each finished puzzle is treated with a special solution to re-bind the paper and return it to being a continuous surface, as close to the original watercolour as possible. After the solution is applied, the wooden support is removed, and the painting is sent to the port where it was painted. Exactly 20 years to the day after it was painted, the painting is placed in a detergent solution until the colours dissolve, the solution is returned to the sea, and the now blank paper is returned to Bartlebooth as proof that the actions have been completed.

Sometimes artists need to follow very strange paths in order to fulfil their ideas, for instance Simon Starling's 'ShedBoatShed' work, which consisted of him dismantling a shed turning it into a boat; loading the boat with the remains of the shed, then padding the boat down the Rhine to a museum in Basel, finally dismantling the boat and re-making it back into a shed.

In the past, Starling has flown to Ecuador in search of balsawood to make a model airplane that would fly over a museum in Australia. He has also immersed a copy of a Henry Moore sculpture in North America's Great Lakes for 18 months before retrieving it to exhibit it encrusted in a carapace of mussels. It is the initial idea, the research and the voyage, that are important in Starling's work and the mock heroics needed to actualise the ideas. It is the heroics of tracking down the materials, persuading people to help and the trips to strange places, that fix his ideas in our minds. The funny thing about humour is that it can point out how useless so many of life's activities are, we can all be complicit in distracting ourselves by performing odd and strange private rituals.

But back to the exhibition. In Yonatan Vinitsky's work he uses nails in the wall as if they are the dots in dot to dot drawings, and then joins them with thick rubber elastic pulled taut between each nail. In this case he is referencing old cartoon gags, such as the man who escapes through the ceiling or the fireman that slides down the pole only to find himself back in the old fire station.

Yonatan Vinitsky

Christian Jankowski's 'I love the art' quote is taken from one of those gallery comments books which are always left there for visitors to write in. By turning what would have been a throwaway comment into a neon sign, Vinitsky manages to reflect on the original intention and make the sign into something to love too. The throwaway drawing and comment have now been through a crafting process, a process that elevates that moment and perhaps echoes what all the artists in this show want people to do.

Christian Jankowski: I Love the Art

Illustration from the German children's Bimpfi books

Her references to "misjudged Bimpfi" images have helped me have more confidence in my own use of Sooty images. Our anthropomorphic ways of thinking are a central part of human nature, but we are only supposed to think like this when young and we are supposed to grow out of it.

Amelie von Wulffen

By dealing with these 'children's images Amelie von Wulffen begins to overcome issues such as the idea of guilt that we carry with us from our early life. These anthropomorphic fruits are however not funny, just funny peculiar, they are perhaps what is waiting behind that door when you go to open it on hearing them knocking.

ARTISTS in the 'knock knock' exhibition

Eleanor Antin, Simeon Barclay, Chila Kumari Burman, Maurizio Cattelan, Heman Chong, Martin Creed, Danielle Dean, Ceal Floyer, Tom Friedman, Ryan Gander, Gelitin, Rodney Graham, Lucy Gunning, Matthew Higgs, Judith Hopf, Jamie Isenstein, Christian Jankowski, Barbara Kruger, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Roy Lichtenstein, Sarah Lucas, Basim Magdy, Suds McKenna, Jill McKnight, Jayson Musson, Harold Offeh, Hardeep Pandhal, Joyce Pensato, Ugo Rondinone, Lily van der Stokker, Pilvi Takala, Rosemarie Trockel, Yonatan Vinitsky, Rebecca Warren, Bedwyr Williams and Amelie von Wulffen.

Related reading:

Sigmund Freud's 'The Joke and Its Relation to the Unconscious'

Cathcart and Klein 'I Think, Therefore I Draw'

Glen Baxter drawings

Mark Tansey

No comments:

Post a Comment