Tsukioka Yoshitoshi: Maruyama Okyo frightened by his own art

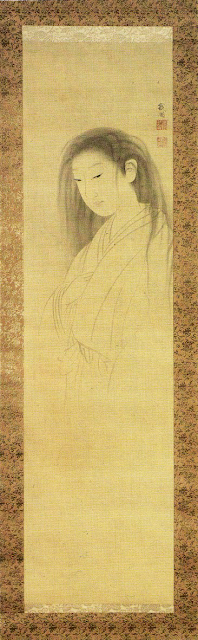

Ghost: Maruyama Okyo

A ghost in the lantern: Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Making art that comes to life is an old myth and one often debunked. Goya depicted Pygmalion with his legs spread wide, cock sure, readying himself to take a mighty swing of the chisel, which is aimed directly at Galatea's crotch. Leaning slightly forward, she looks out with a fearful expression. Goya's interpretation of the well-known myth being a satire on an artist's fantasy. All this artist wants is to open up the woman with his chisel. Goya had seen enough of reality to become very cynical, but as he gets older, his mind also became prey to ghostly images.

Goya: Pygmalion

14th Century manuscript

In this image from a 14th century manuscript, Pygmalion looks as if he is raising Galatea from the dead.

Detail: Pygmalion and Galatea' by Jean-Léon Gérôme

The image we are more familiar with is the one made popular during the Victorian age; Jean-Léon Gérôme's idea of being able to have access to a nude nubile woman in the privacy of the studio, being typical of the way classical art subjects were used as a sort of cover up for the fact that some men just wanted an excuse to be able to put pornography up on their walls. The central issue with the Pygmalion myth being that it suggests that the only relationship humans have with the inanimate is one of desire. We want things to be moulded in our image; we pride ourselves on being superior to everything else. In Genesis, it is stated then God said, “Let Us make man in Our image, after Our likeness, to rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air, over the livestock, and over all the earth itself and every creature that crawls upon it.” A statement that has in many ways led to an uncomfortable relationship with the rest of the world. How can you have a proper dialogue with all the other things that you are entangled with, if you believe in your innate superiority to everything else? To rule suggests that you make your subjects give you tribute; you take the things you want. In contrast, animism suggests that you are just one voice amongst many and that in order to make your way in this world you need to find an accommodation or mediated position between the needs you have and the needs that all other things have. Reciprocity is central to the animist world view.

However there is a totally different approach to the idea of bringing the inanimate to life and that is to depict what is inanimate in such a way that it feels like it is alive. Jim Dine's drawings and prints of tools are a good example of how the techniques normally involved in giving expression and atmospheric quality to representations of human beings, can be applied to inanimate objects in order to suggest that they too have a life of their own.

Jim Dine: Etching

Jim Dine: Lithograph

These images of tools could also be seen as 'portraits' of inanimate objects. Their bi-lateral symmetry makes for a very easy human/tool association; after all tools are extensions of ourselves.

Van Gogh: Boots

These boots have as much life in them as the person that has just taken them off. They can also be thought of as a type of 'synecdoche', whereby a part of something can represent the whole. For instance a boot could represent an army, in this case two old worn shoes, stand in for the person who would normally wear them, a working peasant, and thus all working peasants.

But this is just a small step into the world of the animist. These objects are extensions of ourselves but as we become aware that an old boot can have some sort of élan vital, then perhaps anything inanimate or animate can too, not just things that have a close association with ourselves.

It is the Earth itself that we need to find a proper relationship with. If it has any sort of consciousness I would have thought it would be pretty fed up with humans right now. The Earth's spirit is something we ignore, repress or deny at our peril but we can learn to begin a new relationship with it by turning to other cultures. There is a Japanese term, 'Tsuchi' that as well as being a symbol for the Earth, is also something that can stand for mud, clay or earth. In some animist thought the Earth itself can therefore be held in our hands when a form is made in ceramic. A spirit inhabits the clay, which is itself part of the spirit of the world, the Earth itself. A ceramic vessel can therefore, become a holder of a part of the primordial Earth's soul.

Meditation and deep contemplation, may begin a new dialog between a material and ourselves and once a basic material such as clay and mud is seen as being worthy of our love and care, then hopefully all the other materials and inhabitants of the Earth; animal, vegetable and mineral, become linked to an awareness of a pulse beyond our own, one that gives us a sensual and tactile connection with the charge of life forces that vibrates through everything. An awareness that activates for us what some people used to think of as the non-moving stillness of the inanimate or the dead. In fact the inanimate is never that, all things are in reality animate; the dead are also therefore still alive. Deep within all matter lies energy.

Meditation and deep contemplation, may begin a new dialog between a material and ourselves and once a basic material such as clay and mud is seen as being worthy of our love and care, then hopefully all the other materials and inhabitants of the Earth; animal, vegetable and mineral, become linked to an awareness of a pulse beyond our own, one that gives us a sensual and tactile connection with the charge of life forces that vibrates through everything. An awareness that activates for us what some people used to think of as the non-moving stillness of the inanimate or the dead. In fact the inanimate is never that, all things are in reality animate; the dead are also therefore still alive. Deep within all matter lies energy.

Iranian area: 1,000 BC

You can sense that when this vessel was made that the maker saw many things at once. The material possibilities of the making and a love for the clay, an awareness of the spirits of animal forms and a feeling for how this vessel would be integrated into daily life. It pulls together various conversations with the non-human world and makes them also very human. You feel that this object is of the Earth not something ripped out of it to make some form of profit.

As my own work develops and I have more time for it since retiring, I'm drawn more and more towards animist ways of thinking and the idea of objects being mediators between ourselves and the world. In this case an awareness of how as a boy I used a Sooty puppet as a mediator between myself and the frightening complexities of the adult world; it was in psychiatric terms, a 'transitional object'. I was a young animist, but never realised it.

No comments:

Post a Comment