Werner's Nomenclature of Colours

Werner’s work was translated into English by Thomas Weaver in 1805 and in 1814 Patrick Syme, a flower painter who worked for the Wernerian and Horticultural Societies of Edinburgh, published a revised version, as entitled above. Syme used the actual minerals described by Werner to create the colour charts in the book, enhancing them with examples from flora and fauna. In pre-photographic times visual details could only be captured by drawing and painting, therefore because only trained experts had these skills, scientists put far more importance on verbal description, and scientific observers could not afford ambiguity in their descriptions. Werner's handbook became an invaluable resource for naturalists and anthropologists, including Charles Darwin, who used it to identify colours in nature during his seminal voyage on the HMS Beagle. Werner's terminology lent both precision and because of the words chosen, a certain lyricism to Darwin's writings, enabling his readers to envision a world they would never see.

Of course this had many benefits and it enabled great scientific advances, however there was a darker side to this process. Because they are now able to fix colours, (I'm using fix in a similar way to how fix operates when developing a photograph in a wet darkroom) nouns were able to take over colour experiences, nail them down and in effect own them. Something that had always been integrated within the wholeness of light, that was constantly in flux was now pinned down, so that the scientifically minded collector could own yet another part of a world that should never be owned. It is also but a small step to move from owning and fixing down a particular colour, to owning and fixing down a person of a different colour to yourself.

You might think this harsh of me, and only see Werner's work as an extension of the Enlightenment project, whereby 'mankind' sought to understand the workings of the world in order to achieve mastery over it. But in developing a mindset that presumes mastery over things, that mindset begins to see the world in terms of control and one way of controlling this is by breaking it down into small pieces so that you can examine it. Foucault was a writer that spent most of his life trying to detail this, paradoxically using the very techniques of observational research to try to understand how our modern disciplinary society emerged by closely observing and detailing how control had been achieved. He pointed out that there were three primary techniques of control: hierarchical observation, normalising judgment, and examination, and that control over people (power), can be achieved merely by observing them. For myself my disquiet emerges from the fact that these systems can easily lead to a righteous belief in the self ownership of power, and a use of words such as 'logical' and 'scientific' to justify the most heinous crimes. As an artist perhaps my job is also to point out that even within the most rigorous classification system there is poetry and that no matter how hard humans try to eradicate this in their attempts to become 'objective' they will always fail, because they cant escape the fact that all those ideas emerge from a body that will always be blood and bone and snot and mucus and most importantly of all be made up of over 50% bacteria, a life form that has used humans as hosts for as long as humans have been around, a life form that used other animals as hosts for millions of years before we emerged as a separate species and that will I presume carry on using big lumps of moving animal substances as hosts for millions of more years. To bacteria hosts are all the same, simply bags of warm sea water with lots of added nutrients. The fact that the bag has evolved skills in using rulers and statistics, is in fact beside the point, the bacteria inside you will be far more interested in where your last meal came from and what it consisted of. This fact, I would hope, reminds us of our inconsequence in the real grand order of things and that when we think we have control, we are always in reality being controlled, and perhaps by the very things we have often totally ignored.

The naming of colour does have though another side to it. Instead of using the process to classify and control the world we can use it to develop a much more intimate relationship with it and it is in that process that a sort of poetry emerges.

Details of pages from Werner's Nomenclature of Colours

As Patrick Syme lays out Werner's system you cant escape the fact that he is a flower painter and from chosen names you also cant escape the fact that Werner was German. This is where the poetry comes from. I will leave you as a reader to imagine 'Berlin Blue', I wonder how it sits in the colour classification of cities, perhaps between 'Shanghai Cerulean' and 'Tokyo Turquoise'. In my minds eye I see Syme's poetic number 51, a Bluish Green, a colour shining through the undergrowth, a glimpse of the egg of a thrush, a vision seen under a disk of wild rose leaves, a hint of the colour of beryl, a reminder of its close relationship with a wild emerald green, an emerald as yet uncut and waiting to be set into nature's crown.

The naming of colours continues and every paint manufacturer has its own particular proclivities. Farrell and Ball for instance are supposed to cater for the more sophisticated colour consumer and their nomenclature is not without humour. Here are a few.

I particularly like 'Pale Hound' I wonder if this relates to someone's Labrador? Yonder has to be a pale blue.

Sarcoline, although not a Farrell and Ball colour, sounds as if it should be, it is in fact one of the 'skin' colours.

The full Sarcoline tonal range

An interesting range and much better than those pink ranges for skin that used to be called 'flesh', I would though suggest ringing the doctor if you meet anyone with skin sitting in the yellow range as it will probably be a sign of jaundice. Webster's dictionary just says 'flesh coloured' when describing 'sarcoline' but when you see a Pantone swatch like the one above you realise this definition includes a very wide range of possibilities. However I have a sneaking suspicion that the first use of the colour as a flesh tone was the large slab of it at the top.

'Sarcoline' skin enhancer

In fact if you type in 'sarcoline' as a colour this is what you get, the rectangular block that I have placed right up against the various skin types below, which is very similar to the large swatch further above. What is meant by sarcoline as a 'flesh colour', is another colour that some would point to a being similar to caucasian skin.

Checking out sarcoline as a flesh colour

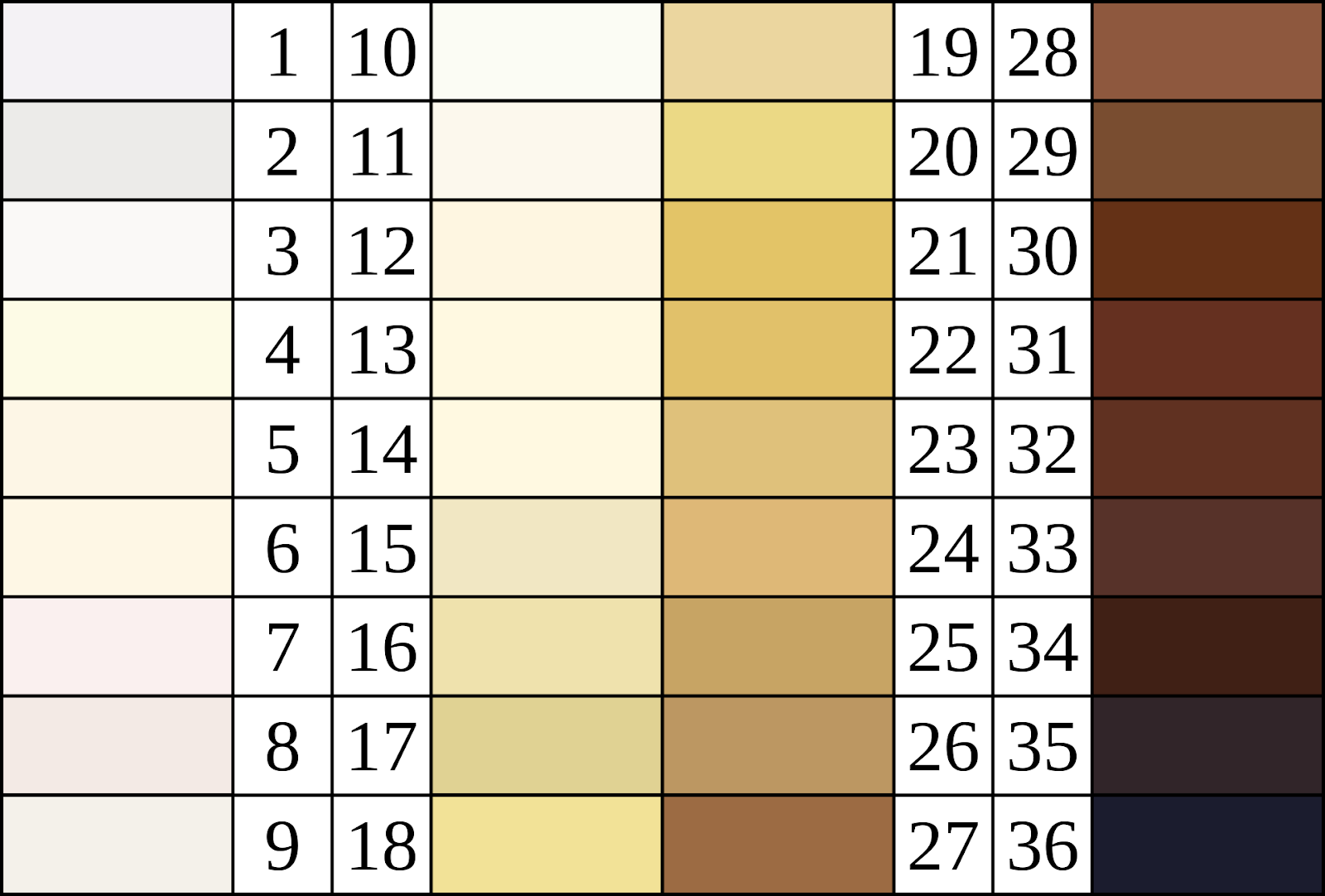

We enter deep and very dangerous waters here. As we know racial classification was often done using skin colour. Von Luschan's chromatic scale is the one set out below, which used 36 opaque glass tiles, that were compared to the subject's skin, ideally in a place which would not be exposed to the sun (such as under the arm). It was used in the early 20th century and is of course associated with the policies of Nazi Germany during the second world war.

Fitzpatrick Scale for the classification of the skin type of individuals was introduced in 1975 by Harvard dermatologist Thomas Fitzpatrick and it was used to describe sun tanning behaviour.

- Ivory

- Beige

- Light brown

- Medium brown

- Dark brown

- Very dark brown

Colour is a very emotive subject. Our relationship with it can begin in the colour of the very skin we inhabit. By giving things names, by measuring them, we replace experience with fixed attributes; we nail things down and in effect exercise power over them. Colours that were constantly in flux, are like butterflies in a Victorian collector's case, pinned down. We all need to be vigilant, because it is but a small step to move from owning and fixing down a particular colour, to owning and fixing down a person of a different skin colour to yourself. What's in a name? Sometimes things we don't want to name.

Coda

Since posting a few days ago I have become aware of a related and for myself very worrying issue; the trademarking of colours.

In the 1950s Owens-Corning, a fibreglass insulation maker was facing steep competition from other companies. At the time, insulation material was all “naturally tan” so to distinguish itself, Owens-Corning decided to dye their insulation material pink. Using 'pink' as an insulation marketing tool; it adopted the slogan “think pink."

In 1985 Owens-Corning became the first company in American history to successfully trademark a colour. In the decades since, a number of companies have successfully trademarked single colours and below are set out a few. As I pointed out, once you can measure something, someone else can own it. In this case the measuring system is that of the 2,139 Pantone Spot Colours. |

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment