William Kentridge

The William Kentridge exhibition that has just finished at the Royal Academy provided us with a wonderful example of an artist working across genres and being inventive in a wide variety of ways. One of the tools he uses when inventing compositions and movements for both human and animal subjects is to make cut out forms that can then be fixed to each other using simple joints. I love this articulated thinking, and have used it myself, both as something totally two dimensional and as a way to think about linking more three dimensional forms together.

Making articulated figures is a very old way of working and Kentridge isn't the only artist who still uses this technique, Clive Hicks-Jenkins also uses it productively.

In the image above you can see the various cut out body parts and their associated clothing being assembled. This is not about cutting out complicated forms, in fact the simpler the better, you do though need to have an idea of how joints will be made and where to place them. I use split pin butterfly clips to make my own jointed figures, but have also used paper clips, wire and string.

Split pin butterfly clips

You can of course simply stitch a joint using thread, use a small piece of twisted wire, anything that allows you to make a joint. Once you begin working like this you can be very playful, perhaps you might make a short animated film of the movement possibilities. Don't forget overall image effect. Because you are cutting out shapes you tend to be much simpler or bolder in your thinking; the forms that make up a figure therefore become much clearer. We all have an unfortunate tendency to get trapped into details and this really does help to avoid this. When you begin to make any drawing or textural indications within these shapes it is therefore useful to maintain a simple but clear way of visual thinking. Look at the trousers in the figure below.

The movement of cloth and associated folds in the trousers has been reduced to a few bold marks, this allows for the trouser forms to sit comfortably within the dynamic of the overall composition of arms and legs and body parts; i. e. they are integrated into the gestalt of the whole image.

You can see this process developing as the image evolves. The simple forms of a cut out coat are integrated into the totality by another set of marks that suggest both the edges of the coat's collar and the play of shadow across creased fabric. The problem would be if you tried to give the fabric a realistic finish, it would not sit well within the simple forms of a cut out.

Simplified drawing on head and hands and torso, kept visually separate by simply changing colour

Clive Hicks-Jenkins

Clive states that he begins with a maquette, starting with a paper template and working his way to a fully rendered figure. Once he has the figure made he can play and try out compositional experimentation. He takes photographs and makes sketches as he makes these changes, something that as students you all need to do, so that you can visually explain the processes that lie behind your decision making. Finally for Clive a drawing takes shape, and then in his case often a painting begins. The result will often be quite different to what he had in mind when he started out, as he points out, these things take their own directions. They are what they are. However, as they begin as flat, articulated figures, something of that origin has to remain in the final work.

Clive Hicks-Jenkins

If you look closely at Clive's articulated cut out wolf, the language of animal hair comes from the same visual language set as folds in clothing. It is simple and bold enough to sit against the cut out shapes that make up the creature.

This way of working was sometimes used by early animators, my own favourite being Lotte Reiniger.

Lotte Reiniger.

You can see Lotte Reiniger's influence on William Kentridge, his own animations owing much to her sophisticated shadow play and of course all of these artists owe a debt to historical folk traditions such as Chinese and Indonesian shadow puppetry.

Indonesian shadow puppetry

I'm very aware that several students have asked me about portraiture and this approach can be a very interesting way to break out of old habits in terms of facial depiction and composition.

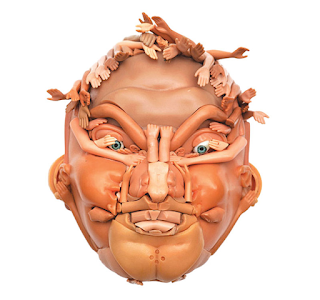

Tim Hawkinson. Emoter

I have posted on Tim Hawkinson's Emoter a while ago and I think it is still worthwhile looking at his approach but this time in terms of portraiture. He breaks a face down into units, just as the body can itself be broken down. He uses blown up photographs of his own face to do this, so the type of simplification that drawing can produce isn't available to him, but the implications are still there. You could build a face in the same way that a body is constructed.

Muscle structure of the face

Face mask with articulated jaw "elu" ("spirit") Nigeria, Ogoni

The degree of simplification you bring to this process will determine the visual look or feel of the images made. Compare the Nigerian face mask with an articulated jaw above, with a face made by Freya Jobbins from recycled dolls and the early 20th century paper toy face further below.

Freya Jobbins

Paper toy face

The world of toys is another area of endless fascination in relation to these issues. Mr Potato Man has a wide variety of body and face parts now available to buy as extras that mean you can extend your Potato Man ideas even further.

Mr Potato Man mouths

A Mr Potato Man mouth

When you look closely at the mouth forms that the plastic additions come in you may well find that they are very strange abstractions. The mouth above could be a design for an abstract painting. The more we separate a whole into parts, the more each part can become loosened from its original function. This process of atomisation is one that we are very good at, but which has also led us as a species to be able to cut up interconnected eco systems and divide the world into dis-functioning units. Every way of thinking has its effects on reality, and hopefully before we apply these conceptual models we think through their consequences.

However it is in shadow puppetry that the most deeply mystical and spiritual of articulated images emerge. Like the cave wall that acted as a membrane between the world of the spirit and the world of the everyday, the thin sheet upon which the shadows move is another delicate membrane that sits between the world of the imagination and of reality.

A figure from the Javanese shadow-puppet tradition of Wayang Kulit

Clive Hicks Jenkins has an excellent blog and he has given a far better explanation of the history of shadow puppets than I could ever manage, so do click on the link and read what he has to say about this wonderful art. Christian Boltanski

Various contemporary artists have returned to articulated shadow puppetry, and as well as William Kentridge, Christian Boltanski and Kara Walker have made extensive use of the technique.

Kara Walker

The Chinese pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale saw the artists Wang Tianwen, Tang Nannan, and Yao Huifen working together to present ‘Removing the mountains from and filling the sea’, a shadow theatre performance.

Wang Tianwen, Tang Nannan, Yao Huifen: Removing the mountains from and filling the sea

Wang Tianwen, Tang Nannan and Yao Huifen combined new and old technologies to make the work. Traditional skills in making the shadow puppets were combined with computer driven armatures, whilst some components were still fixed to bamboo sticks, such as the waves you can see in the image above. Their work reminds us that old and new technologies are in reality the norm. We keep using what works, whilst we invent new forms, and the one sits alongside the other. We forget that painting is an art form thousands of years old and happily go to exhibitions where it sits side by side with video projections and we have kitchens full of modern gadgets that sit alongside utensils that have changed little since Medieval times.

It is not just artists that have thought of breaking forms down in this way. Detecting people in images is a key problem for video indexing, browsing and retrieval. The main difficulties are the large appearance variations caused by action, clothing, illumination, viewpoint and scale. Therefore the people that break down images for indexing, represent people use a 2D articulated appearance model composed of 15 part-aligned image rectangles surrounding the projections of body parts: the complete body, the head, the torso, and the left and right upper arms, forearms, hands, thighs, calves and feet. Each body part is numbered so that a numerical filing system can be applied to the images.

From: Learning to Parse Pictures of People: Remi Ronfard: 2002

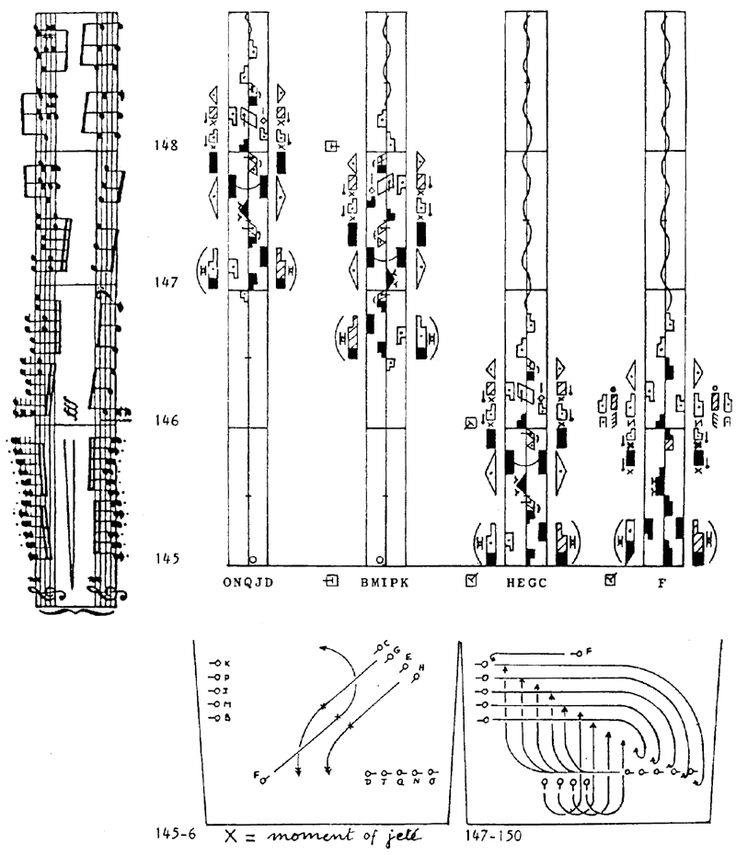

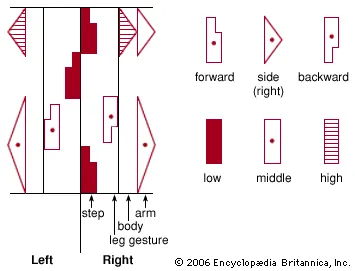

This way of visualising computer images of the body is now 20 years old and is no doubt in the scientific world of computing redundant, but it might be interesting to combine it with Laban notation.

Laban notation

Of course once you begin looking at how to move a real body in terms of articulating it in sections you could take the idea out into performance and that could be a wonderful new beginning for the idea. What if we could extend or join certain parts?

Rebecca Horn: Finger gloves

All of these thoughts have led me towards my own attempts to work with articulated body parts in an animation.

One of several articulated figures that are going to eventually feature in an animation.

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment