William Anastasi: Pocket Drawings

In 1969 William Anastasi folded a sheet of paper into eight rectangles, making them the same size as his back trouser pocket. As he walked, he held a tiny, soft pencil against the exposed paper inside the cramped space of his pocket; the resulting marks on the unfolded sheet of paper graphed the activity. When he decided a drawing on one section was finished, he refolded the sheet, creating a new blank surface, and the process began again until all eight rectangles had been used.

He was the first artist I ever came across to suggest that walking was good for thinking, something I still believe is true. “I love walking,” he said, “I find that walking does something to my thinking, to my mental process, that is different from sitting or lying down.”

When I was an art student in the late 60s and early 70s undertaking my DipAD, conceptual art was a very powerful shaper of possibilities and the musician John Cage and the artists associated with his practices were vital to the milieu that these ideas were emerging from. One of the artists central to these practices was William Anastasi and I thought it would be useful to remind both myself and those of you that read this blog, how influential at the time his work was.

When I was an art student in the late 60s and early 70s undertaking my DipAD, conceptual art was a very powerful shaper of possibilities and the musician John Cage and the artists associated with his practices were vital to the milieu that these ideas were emerging from. One of the artists central to these practices was William Anastasi and I thought it would be useful to remind both myself and those of you that read this blog, how influential at the time his work was.

William Anastasi: Reading a Line on a wall: 1967

In Kosuth's case, by assembling three alternative representations of a wooden chair, he constructs a platform for exploring representational meaning or how we come to determine what things are; he asks the question, "What are the differences between a 'real' thing, its representation and its definition?" In Anastasi's case, the work's content is also about definitions, and it is also firmly in the present tense, as it refers directly to our reflective sense that during the moment when we read 'READING A LINE ON A WALL', we are reading and all distinctions between the content of the work and the activity of the beholder dissolve into a state of self-awareness, immediacy and a truth statement. It is what it is or a 'what you see is what you get' moment, a type of position that also reflects Frank Stella’s famous statement ‘What you see is what you see’, that became the mantra of Minimalism.

As a viewer you are 'asked' to reflect on the implications of reading the word 'reading', an activity fraught with intellectual pitfalls. It is easy to forget but this was a time of complex aesthetic yet conceptual but also semiotic and philosophical niceties, as unpicked very astutely by Tom Wolfe in his essay 'The painted Word'. As a student in the late 1960s I was quickly made aware of the need to 'read' a work of art as a text. Because of the still heavy influence of Clement Greenberg these 'texts' also had to be self referential, Greenberg's 'Towards a New Laocoon'* advocating a development of Lessing's position that different types of art could only carry certain types of content. For instance according to Greenberg painting could only carry messages about paint, surface and colour and that any additional 'narrative' was false and would be an additional interference. Therefore the most highly regarded paintings and sculptures of the day were those that most thoroughly manifested the essence of their own means of expression through various modes of self-referential production. These might be certain types of brushstrokes, or ways of dividing the canvas into areas of colour, or the artist leaving traces of painterly actions, (Abstract expressionism, the abstract sublime and minimalism were all movements influenced by these theories). Like many of the most conceptually rigorous works from the late 1960s, Anastasi’s drawing confronts the criteria of that narrow aesthetic paradigm in a way that is meant to demonstrate some of the flaws in the argument. For instance the sparse white wall in the drawing is an illusion of a white wall. Typical art galleries now hung art against large clean white walls, which was an idea that will soon be picked apart by Brian O'Doherty in his essay, 'Inside the White Cube, The Ideology of the Gallery Space'. What seems very non figurative is in fact a very highly figurative image, of a gallery wall, therefore a dreaded illusion. In fact it is a drawing of a particular gallery wall, the arrangement of air vents, electrical sockets and moulding corresponding precisely to one particular wall of the Virginia Dwan Gallery in New York. The physical flatness of the sheet of paper itself participates fully in the imitation of the wall that the drawing depicts, its size for size correspondence with the actual gallery wall, adding to the conundrum, especially when exhibited on an even larger gallery wall, such as those at MOMA.

You can find some old Bibles with already printed hermeneutic annotations and when these include the individual annotations made by the Bible's owner the reflective layers begin to get more and more fascinating as you begin to realise how as human beings we strive for the 'right' interpretation. However what we only ever arrive at are interpretations, never answers. This is perhaps the central meaning if there is one to Anastasi's 'Reading a Line on a wall'. No matter how carefully a text is read, even with expert guidance it will always remain unknowable. It is easy to forget the powerful role of critics at that time in determining what was good and bad art. In a post-modern world there are as many answers to what is good or bad as there are questions, but back in a time when people still went to Sunday school and were made to read and make sense of their Bible, it didn't seem so strange that someone in 'authority' might try to lay down a definitive interpretation of art.

As a viewer you are 'asked' to reflect on the implications of reading the word 'reading', an activity fraught with intellectual pitfalls. It is easy to forget but this was a time of complex aesthetic yet conceptual but also semiotic and philosophical niceties, as unpicked very astutely by Tom Wolfe in his essay 'The painted Word'. As a student in the late 1960s I was quickly made aware of the need to 'read' a work of art as a text. Because of the still heavy influence of Clement Greenberg these 'texts' also had to be self referential, Greenberg's 'Towards a New Laocoon'* advocating a development of Lessing's position that different types of art could only carry certain types of content. For instance according to Greenberg painting could only carry messages about paint, surface and colour and that any additional 'narrative' was false and would be an additional interference. Therefore the most highly regarded paintings and sculptures of the day were those that most thoroughly manifested the essence of their own means of expression through various modes of self-referential production. These might be certain types of brushstrokes, or ways of dividing the canvas into areas of colour, or the artist leaving traces of painterly actions, (Abstract expressionism, the abstract sublime and minimalism were all movements influenced by these theories). Like many of the most conceptually rigorous works from the late 1960s, Anastasi’s drawing confronts the criteria of that narrow aesthetic paradigm in a way that is meant to demonstrate some of the flaws in the argument. For instance the sparse white wall in the drawing is an illusion of a white wall. Typical art galleries now hung art against large clean white walls, which was an idea that will soon be picked apart by Brian O'Doherty in his essay, 'Inside the White Cube, The Ideology of the Gallery Space'. What seems very non figurative is in fact a very highly figurative image, of a gallery wall, therefore a dreaded illusion. In fact it is a drawing of a particular gallery wall, the arrangement of air vents, electrical sockets and moulding corresponding precisely to one particular wall of the Virginia Dwan Gallery in New York. The physical flatness of the sheet of paper itself participates fully in the imitation of the wall that the drawing depicts, its size for size correspondence with the actual gallery wall, adding to the conundrum, especially when exhibited on an even larger gallery wall, such as those at MOMA.

But which line are we reading? The line that suggests moulding or the line of text? The drawn line or the written line? Both lines are central to their relevant disciplines. Lines are the bedrock of both drawing and writing. However the words 'READING A LINE ON A WALL' are in upper case blocked letter forms and as such they are solid forms rather than lines, which they could have been if Anastasi had used a lower case cursive text. Upper case or capital letters suggest something important, like the capital letters surrounding Roman civic buildings, they are authoritative. As you can see by now, 'READING A LINE ON A WALL' takes a fair bit of reading and for a young lad like myself this set of readings within readings was quite liberating and it opened a door to what is known as 'hermeneutics', the branch of knowledge that deals with interpretation, especially of the Bible, where various interpretations are often found surrounding earlier texts. Layers of meaning nested with layers of meanings.

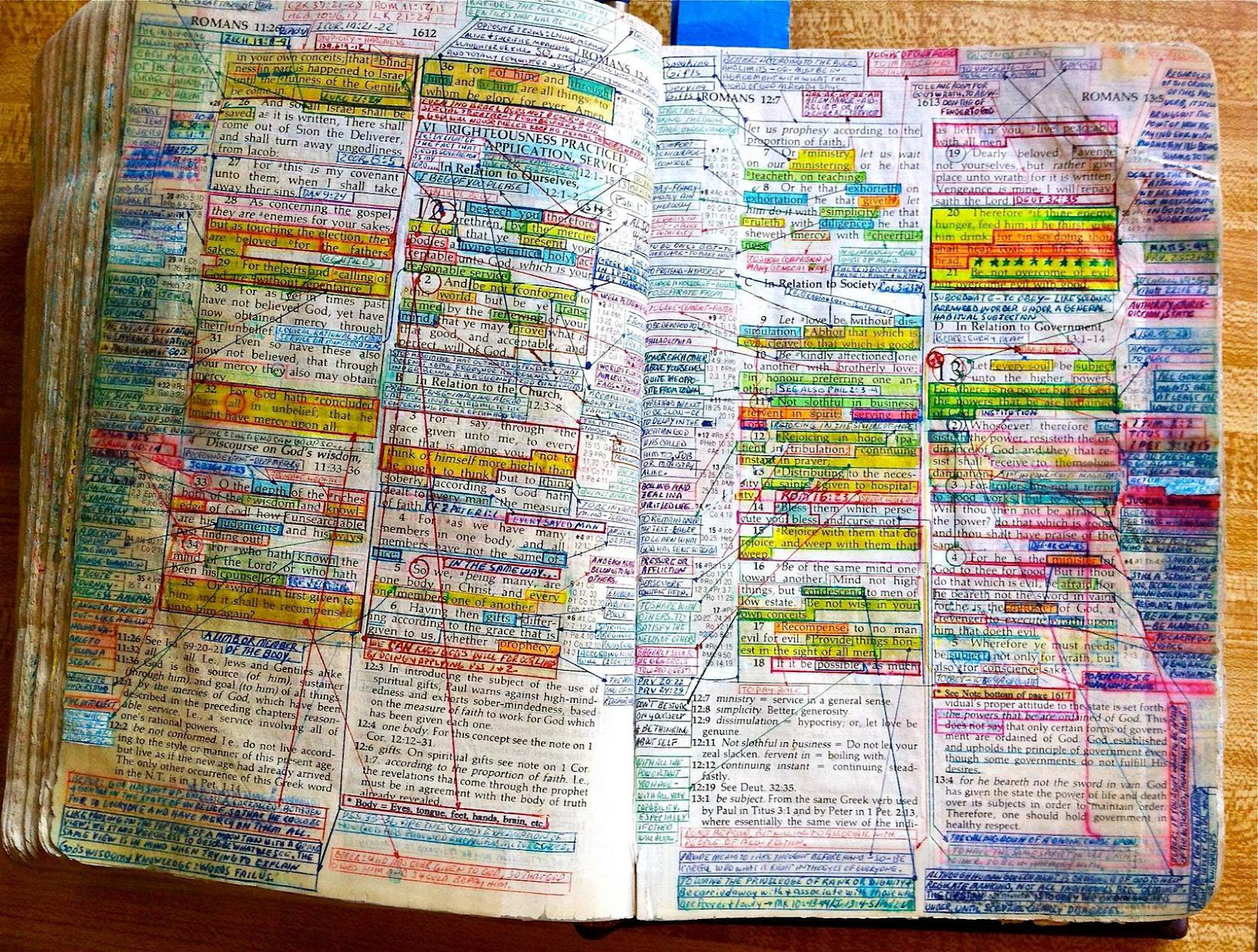

An annotated Bible

You can find some old Bibles with already printed hermeneutic annotations and when these include the individual annotations made by the Bible's owner the reflective layers begin to get more and more fascinating as you begin to realise how as human beings we strive for the 'right' interpretation. However what we only ever arrive at are interpretations, never answers. This is perhaps the central meaning if there is one to Anastasi's 'Reading a Line on a wall'. No matter how carefully a text is read, even with expert guidance it will always remain unknowable. It is easy to forget the powerful role of critics at that time in determining what was good and bad art. In a post-modern world there are as many answers to what is good or bad as there are questions, but back in a time when people still went to Sunday school and were made to read and make sense of their Bible, it didn't seem so strange that someone in 'authority' might try to lay down a definitive interpretation of art.

This type of self referential art was very popular when I was a student and I was at the time sucked into the game, making several pieces of art that 'cleverly' commented (or so I thought at the time) on the activity of art making. I was bamboozled by theory and persuaded that all good and interesting art was always to some extent a reflection on the nature of art itself, by the staff that taught me at that time, Keith Arnatt in particular. It was not until I read Tom Wolfe's text 'The Painted Word' in 1975 that I was able to get past the what had become a block on my own ability to use art to reflect on the wider issues that I had begun to see as being much more worthy of taking up my time. Gradually I began to see that art's spectrum of human awareness included everything from philosophical debates as to how many angels could be found dancing on the head of a pin, to stories about leaving the washing up until tomorrow. In fact the older I got the more I began to realise that the best and most important stories weren't even told by humans, it was just that we like to hear the sound of our own voices. The 'Handmade Bottle Rack' was very much a response to my own history at the time. I had come to art college directly from working in a steel works and I decided to make Duchamp's readymade by hand. I was trying to make a comment about the way his intellectual achievement, had negated the achievement of the 'workers', those who laboured in factories to produce objects like the bottle-rack and who's labour was usually forgotten especially by the sort of people who would use a bottle-rack. (At that time wine drinking was seen as a very middle-class thing to do, working class people drank beer). I was also making a point about the artist's labour and that 'Judd's dictum', "That anything is art as long as somebody calls it art", was another middle class attempt to take away the meaning of labour, skill and craft from those who worked with their hands. Looking back on the work, perhaps its most important aspect was the fact that I made it in such a way that all the materials could be recycled. After exhibition and it being photographed, it was taken apart, and all the materials given back to the workshop where it was made, so that next year's students could use them. If the job of an artwork was to communicate an idea, then once done, like yesterday's newspaper, it was redundant, and the idea of keeping work for posterity was I argued, a middle class idea about the creation of an elite culture and a way of supporting an evil capitalist art world economy that relied on the monetisation of curated ideas.

As a young man I was far more 'militant' in my thinking and found a harsh conflict between what I was being taught and how I felt as someone coming from a working class background. For instance my parents loved 'tranculments', (a Black Country word for ornaments) or as I had begun to think of them, small scale domestic sculptures. They carried ideas such as memories of places visited, (souvenir porcelain miniatures carrying names of seaside towns), reminders of old traditions, (horse brasses), a love of animals, (miniature ceramic dogs) and reminders of war (polished and engraved brass shell cases), but I was quickly educated to see these things as kitsch objects. They were I was told cheesy or tacky, this was apparently not art, these were objects that appealed to popular or uncultivated tastes because they were overly sentimental, and I was being taught to see these things as ugly, without style, false, or in poor taste. But in order to fight back I had to learn the language of middle class art and of course in doing so I received the approval of my tutors, who thought my work at that time was good. I had moved over to the other side and become middle class, my 'educated' stance was understood by other middle class people as clever and the work I did was totally incomprehensible to the rest of my family who still collected souvenirs and polished the horse brasses on weekends.

As contemporary students you may well have similar experiences. What I found as I got older was that all these things are simply aspects of a human condition that is a reflection of how we make sense of the world around us. The problem is that at certain times you will find gatekeepers to the profession that you want to enter. Whether this is your tutor, Clement Greenberg or your local arts council officer, people will have ideas about what art is and what it is for, and you will have to form your own beliefs and set of convictions if you are to practice art on your own terms.

* 'Towards a Newer Laocoön' by Clement Greenberg, was a very influential critical text, the title refers both to Gotthold Lessing's Laocoön: An Essay upon the Limits of Poetry and Painting, of 1766,

and to Irving Babbitt's The New Laokoön: An Essay on Confusion of the Arts, of 1910. Greenberg is interested in the existence of limits or boundaries that distinguished the differences between the various arts. According to Greenberg's

argument, it is a truth value characteristic of modern art that each type of art had to define itself in terms of the

limitations of its 'proper' medium, or in other words to preserve a 'truth to the materials' involved in the practice of the various art forms.

See also:

Who's afraid of Tom Wolfe: Judith Goldman's repost to the Painted Word

Walking and drawing More reflections on the influence of Keith Arnatt but also an introduction to the work of Stanley Brouwn another late 1960s conceptual artist who drew.

Drawing and measurement Another Keith Arnatt reflection

Facing a blank sheet of paper One of my own attempts to make work that reflects on similar issues

The word 'art' and its history

No comments:

Post a Comment