Tenmyouya Hisashi: RX-78-2 Kabuki-mono 2005 Version

I've posted a few times on other cultures and traditions, and the posts have tended to concentrate on the past and the historical legacy that comes with being part of a different culture. However there are other stories and one of the most common is how tradition and contemporaneity coincide. The Japanese artist Tenmyouya Hisashi for instance uses tradition to reflect on contemporary life and at the same time question the notion of tradition itself. His work questions what traditional culture is, not just in relation to Japan but everywhere.

When my son was a young boy he was fascinated by Transformer toys. The Transformers toy line was created by the Japanese company Takara and was initially marketed in Japan under the names of 'Micro Change' and 'Diaclone'. In 1984, the US company Hasbro bought the distribution rights to these toys and re-branded them as 'The Transformers' for a North American audience. The designs for the original figures, all of which could transform from one thing such as a car, aircraft, gun or even a cassette into robots, were made by Japanese artists such as Shōji Kawamori, (who was probably the most well known), but also designers such as Kouzin Ohno, (Ironhide, Jazz, Starscream) and Takayoshi Doi, who designed the Dinobots. I was at the time fascinated by the Insecticons who were designed by Takashi Matsuda. I thought I could see traces of Egyptian scarab beetle sculptures in their design; a design that was constructed so that these toys could transform from insects into robots.

Takashi Matsuda also came up with the form of Megatron, a robot that could also transform into a gun. All of these toys had one thing in common, they could take on more than one identity. A tiny insect could morph into a giant robot, size constancy didn't seem to be a problem for a child's imagination.

The cultural tradition young boys were growing up with in the 1980s and 90s was definably Japanese, especially as Nintendo released their Gameboy in 1990 hot on the heels of the Transformers coming to the UK. Culture within the commercial world of capitalism is global. Hasbro needed English names and associated back stories for the characters, so that they could be marketed to English speaking customers with a narrative that was understandable in relation to Western young boys and their interests and so they approached Marvel Comics and Bob Budiansky was given the job. He conceived the names of many of the original Transformers that would be then released onto the American and European markets, such as Megatron, Ratchet, Starscream, Sideswipe and Ravage. He also wrote the vast majority of the descriptive "tech spec" biographies printed on the Transformers' toy packages, giving each figure unique personality traits in the same way that Marvel superheroes such as Spiderman were constructed. In this way two cultures were blended, the world of Japanese toy design and the superhero world of American comics. The fusion would of course result in Marvel releasing another comic title, The Transformers'.

You can easily spot the historical references in the design of the robot forms.

The robot within Japanese culture is particularly fascinating. It is an object that generates meaning for its Japanese observers and participants within a tradition that is specifically Japanese. Shintoism has been followed in Japan for over a thousand years and it is a religious tradition that embraces animism. Spirits or kami, can be seen to inhabit animals, natural features like mountains and many other non-human things. Therefore the idea of a robot being able to be animated by human like attributes was more easily assimilable by Japanese culture. There had also been a long tradition of automata using clockwork mechanisms. The term 'karakuri ningyō' refers to a variety of clockwork automats created in Japan during the 17th century.

Karakuri = ‘mechanism’ or ‘trick’ / ningyō = a puppet.

A chahakobi ningyō or miniature tea server, was made in the 19th century by Hisashige Tanaka, founder of the Toshiba Corporation which would eventually become a diversified enterprise involved in electronics, electrical equipment and information technology and which is still based in Minato-ku, Tokyo and they of course now make robots for industrial use. The Toshiba Corporation website includes video demonstrations as to how its latest robots can do the work that used to be done by humans.

The next step up in technology to be used to make automata after clockwork was inflatable rubber tube hydraulics. Gakutensoku, a humanoid robot built in 1928 by Nishimura Makoto, used this technology to tilt its head, move its eyes, smile, and puff up its cheeks and chest. It was also programmed to use calligraphy skills. It has recently been reconstructed and a new computer-controlled pneumatic servo system has been designed to keep it going over 90 years after it was first put into operation. What was fascinating about Gakutensoku, was that this was a very early attempt to give human expressions to a robot and cemented the idea into modern culture of robots often being humanoid in form. For myself, I have tended to see this as a continuing form of animism and often think of these forms as being similar to pre-historic shamanistic figures, such as the one illustrated below of a bee faced Algerian shaman figure, that has mushrooms growing all the way around it. This might of course be an indication of early drug use, something that might have helped the shaman get deeper into character. The final form is another hybrid one, an image that suggests that the sharp differences between humans and other creatures is not as sharp as we think it is.

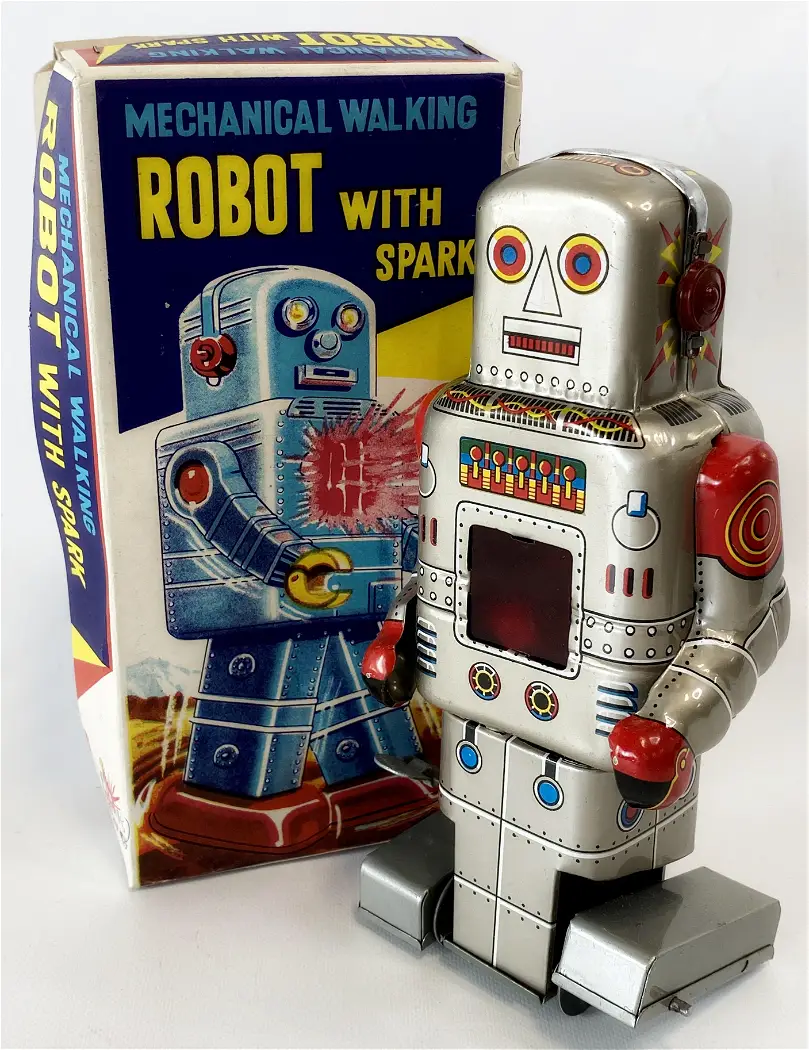

Robots had gradually entered Japanese culture, and there was less of a worry in their society about how their introduction might effect our human lives in the future. Perhaps because they had had to deal with the aftermath of the atomic age of science fiction becoming atomic bomb science fact, the society was much more open to future casting, whatever the reason, the first mass-produced mechanical toy robots were built in Japan following World War II. These wind-up robots, typically made from tin and brightly coloured, captured the world's imagination and were the first step in the development of a new hybrid culture, whereby robots took on humanoid forms.

From Transformers the comic

You can easily spot the historical references in the design of the robot forms.

Traditional samurai armour

Tenmyouya Hisashi

Tenmyouya Hisashi's images illustrate the 'mash up' of traditions that occur as hybrid global cultures emerge. In 2006 the Japanese football team had qualified for the football world cup which was held in Germany. A game originally invented in England, now belonging to a world wide culture, a game that now represented serious international money and that also wanted to celebrate the inclusion of specifically recognisable 'other' cultures as proof that the game was now global. Tenmyouya Hisashi's images were perfect illustrations of this and his work was chosen as one of the posters that celebrated the event. The use of traditional gold leaf backgrounds to his images, now also signifying the background of wealth that at the time surrounded world football. His 'RX-78-2 Kabuki-mono' image of a Transformer toy, constructed again on a gold leaf background and this time with a traditional dragon wrapping itself around the robot, fuses the old and new traditions together in such as way that we are reminded that the robot's design is based on ancient Japanese warrior costumes.

The robot within Japanese culture is particularly fascinating. It is an object that generates meaning for its Japanese observers and participants within a tradition that is specifically Japanese. Shintoism has been followed in Japan for over a thousand years and it is a religious tradition that embraces animism. Spirits or kami, can be seen to inhabit animals, natural features like mountains and many other non-human things. Therefore the idea of a robot being able to be animated by human like attributes was more easily assimilable by Japanese culture. There had also been a long tradition of automata using clockwork mechanisms. The term 'karakuri ningyō' refers to a variety of clockwork automats created in Japan during the 17th century.

Karakuri = ‘mechanism’ or ‘trick’ / ningyō = a puppet.

Chahakobi ningyō

A chahakobi ningyō or miniature tea server, was made in the 19th century by Hisashige Tanaka, founder of the Toshiba Corporation which would eventually become a diversified enterprise involved in electronics, electrical equipment and information technology and which is still based in Minato-ku, Tokyo and they of course now make robots for industrial use. The Toshiba Corporation website includes video demonstrations as to how its latest robots can do the work that used to be done by humans.

Current Toshiba Corporation video of robot use

Samurai armour the traditional form behind the modern icon

By the time that films such as Pacific Rim came out in the 21st century, the visual idea of what a robot should be like had been fixed, its Japanese lineage now locked fast into a global idea.

Design for a giant robot for the film Pacific Rim

Another culture has been mixed into the hybridity in the image above, that of the engineering 'blueprint'. This is used to give 'scientific veracity' to the design. A design which itself relies heavily on the ideas that came out of Japan in the 1980s, the forms and shapes of which were rooted in traditional samurai armour. The following my nose 'logic' of this post seems to be outlining a post-modernist idea of culture, but I didn't set out to imply that this was what I thought contemporary society was about. I was simply trying to unpack a few thoughts set into motion by looking at some Tenmyouya Hisashi images. As students sometimes it is worthwhile doing the same thing and what it often reveals is the importance of children's culture on what will become an adult world. When I asked the highly regarded contemporary sculptor Thomas Houseago where he thought his main sculptural ideas came out of, he told me that Sesame Street was right up there as one of his main influences.

For myself it was perhaps Sooty and The Flowerpot Men that have stayed with me all these years, which were, it could be argued, deeply animist ideas as well. In fact at one point I tried to bring images from the two worlds of puppets and humanoid robots together, fused around a memory of when my mother worked as an usherette in the Gaumont Cinema in Dudley during the late 1950s. I found the film so frightening, I had to get my Sooty puppet to watch it instead.

I'm now living in an age that recycles the remains of the culture of my youth. Little Weed from the 1950s TV series 'The Flowerpot Men' seemingly a much more threatening thing now than she was at the time; she is no longer the polite weed of yesterday. In a time of global warming and ecological disaster, the taking seriously the life of a weed, seems so much more important and her sagacious advice to the flowerpot men, now seems more like a metaphor and a parable for about how we should have been listening much more closely to nature in the past, and that if we don't in the future, all of us will find ourselves redundant not just 1950s children's puppet shows.

Capitalism is driven by a constant need for new forms, so what is current for one generation is totally outdated by the time the next generation comes through. This is something most of human society historically would have found very strange. In the distant past change was very slow and your grandparents' culture would have been virtually the same as the one you would experience. However our propensity for an animist relationship with non human things still remains a powerful force, so I am hopeful that we might eventually begin to treat the world as a living, complex entity, rather than a resource to buy and sell. We still have to deal with our existentialist angst and buying new things never did bring happiness, but reflecting on these issues can at least bring us some sort of awareness and in awareness lies knowledge and in knowledge lies wisdom and in wisdom lies the overcoming of the sadness caused by desire.

Thanks for posting such an amazing article. Both the toys were kind of a Educational Toys for Children with their unique collections of toys.

ReplyDelete