It is always fascinating to see the final selection and winners that are picked out in the annual Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize. It works as a sort of litmus test as to the current state of drawing led practices and especially this year in a time of lockdown. My own added personal interest was that I had submitted a collaborative piece this year, that made it through the first round but no further; so I was of course fascinated to see what did win.

M. Lohrum’s 'You are It' was the overall prize winner and for the first time a performative drawing has won. It reminded me of Sol Lewitt drawings that were also made from written rules, his impermanent wall drawings consisting of sets of the artist's instructions, so that their actual execution could be carried out by someone else. There is though a difference. In M. Lohrum’s case the audience is engaged directly in the drawing's execution, in Lewitt's case it was usually student volunteers or gallery staff who made the drawings and when you did get to see the work it was usually already completed.

M. Lohrum is less 'authorial' in the control of the work, and there is more an emphasis on collaboration and participation, which I think reflects a shift in attitudes that has taken place since Lewitt began producing his work in the late 60s. Lewitt came from a time when the status of the artist was more or less unquestioned, artists were the avant-garde, the romantic initiators of new ideas and as such their name was very important, as it was used to in effect 'brand' their practice. We are living in different times, the status of the artist has been questioned and in particular the role of the artist as maker of 'honorific objects' that are to be collected by rich individuals and displayed as cultural capital in museums and art galleries is perhaps coming to an end. Of course the art market still exists, but it seems to have less and less relevance to many an artist's everyday life. My own recent experience is that as an artist I have become more embroiled in interdisciplinary activities, especially those related to health and wellbeing. The artist still has a role in society, but perhaps it is one shifting away from a capitalist idea of the producer of a particularly rare cultural commodity and is moving gradually towards an idea of the artist as catalyst or instigator of alternative ways of approaching life. Artists have always been associated with raising awareness, seeing something more in the everyday than the everyday, and it would seem that in times of a lockdown we need this quality more than ever. As the selector Frances Morris stated “The invitation to members of the public to participate as anonymous makers and the work’s dependency on collaboration between strangers, felt timely and necessary, speaking to the power of art to bring people together”. It is not of course just that a work like this brings people together, it also reminds us of the central position of our bodies in the making of meaning. Every drawing that has ever been made is in one way or another a seismographic record of the person that made it. Each one of us has a different ratio of arm length to height and to hand size; we are all unique in relation to the type of heart beat we build our life's rhythm to and in the way that our nervous systems are wired up. Each person participating in this drawing, as they are instructed to draw from their shoulder will immediately be aware of the weight of their own arm and of how well it operates as it moves around in its shoulder socket. Body awareness is of course vital if we are to maintain a sense of our own well being, an awareness not just of our selves but of other people's bodies is essential to the building of empathy with others and the development of our collective sense of community care.

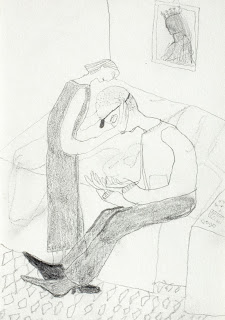

It was very interesting therefore to see that the second prize had been awarded to Nancy Haslam-Chance for her 'Caring Drawings'. These pencil drawings are a long way from the fine artist's 'signature' drawings that forefront a special touch or individuality of approach and instead these drawings document her role as a carer and support worker. These drawings are more like those we might find in a visual diary, and they focus on the physical and emotional relationships she has formed with her clients. The daily details and practicalities of her job are drawn from memory between shifts, an important reminder that artists need to ground their practice in reality if it is to communicate to others. This type of reality has of course in a time of COVID become much more visible, but carers have always been there working to support other human beings who have fallen on hard times, we just needed a reminder and Haslam-Chance has given it to us.

Both these artists have produced work that has emerged out of a crisis, one that will hopefully have been overcome by the time the next Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing competition is run. I would hope though that what their work intimates is that there is a move towards a rethinking of the role of the artist in society. A role that is less to do with individualism and one much more to do with self awareness, community cohesion and spiritual well being.

Reference

LeWitt, S 1967, “Paragraphs on conceptual art”. Artforum, vol.5, no.10, p.79

See also: