I have been working as an art educator for nearly 50 years. Today begins another year, and alongside making resolutions and hoping for new experiences, it is perhaps time to reflect again on what I'm doing. It is very easy to become stuck in one's ways and to allow experience to become a stick with which to beat people with, as opposed to it being something that can be drawn upon as an aid for others or as a help for them to make their own decisions when they need to find the best pathway to take. Recently Art21 asked art educators to reflect on what they thought they were doing and I was in particular interested in what Amiko Matsuo had to say about the art educator as connector. Matsuo had this to say when writing about her own approach to drawing to our attention the tapestry work of Otobung Nkanga.

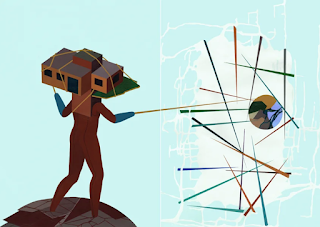

'I walk to the larger textile: a map or network layered and woven in the cosmos. The edge of the textile welcomes a figure about to step forward without feet or a brain. It enters the plane on the wall next to urchiny tree branches. Is the figure tethered to circular captions? Is it directing the mechanical arms to pull at the bubble captions? Floating, it feels unmoored even as it appears to be hard at work'.

Matsuo points out how she attempts to translate for her students the sense of connectivity and geopolitics that she finds represented in Nkanga's work. She hears her own voice as an arts educator participating in the witnessing and telling of such stories and states that her understanding arrives via a lens of who she is right now and that the collective work of the art educator brings together an awareness of art, artists, other art educators and students, something that as a process she feels both defines her and expands far beyond her.

The fact that Amiko Matsuo begins by stating that it is her own voice that is central to the witnessing and telling of stories and that she understands artwork through 'a lens of who I am' was I thought spot on. I also thought that it was important to remind everyone that she is also interconnected with a rhizomatic network of artists and other teachers and that her role is to try and connect others that she encounters with that network. She teaches ceramics and has had to think hard about how her own experience can be used to open out new possibilities for an area of creativity that has often been far too constricted in its use as a fine art material, by being seen as 'pottery' or looked at through a very Western lens as 'craft'. Above all she asks open ended questions, suggesting that her students have as much ownership of answers to these questions as she does. She reminds me that as a white, male, Anglo-Saxon I have to be very careful to continue opening myself up to wider and wider forms of thinking in relation to art practices. This is hopefully something I try to constantly work on, being very aware that my background is one of white, male privilege, but at the same time, I still feel able to make work about what it is to be who I have been and reflect on my time as an artist who has emerged from a working class Black Country, English town and who has attempted to always come to terms with life through the practice of making art. We are who we are, but that doesn't mean that we should be complacent, we need to keep on striving to be more aware, to watch what is going on and to uncover the many histories that lie behind the things we experience. As well as trying to remain self aware and trying to keep myself open to changing sociological patterns in both art and society, I have also had to think about why I might still be of value to a community of practitioners. Olivia Laing, in her book 'Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency', looks to find a stance for her writing that as she puts it, avoids 'paranoid reading'. I.e. the world is so full of horrid and worrying things that it is too easy to spend most of our time unpicking the wounds of modern life. I agree with her and would like to think that an aspect of my role as an art educator and as an artist is to look for things that are positive possibilities, that are speculative futures that suggest life affirming directions of travel, rather than using my activities to erect static platforms from which to rage and shout about the tragic consequences of our present day political realities. As Laing puts it, to be 'more invested in finding nourishment than identifying poison'. (Laing, 2021, p.4)

The readers of this blog as well as current and past students will of course be the judges of whether or not I manage to provide a fertile soil with which to nourish practice or whether I have just missed the point and that art practice is now somewhere totally different and that it is time for me to retire. I still though have a belief in a practice that has at times been compared to a religion. It has been argued that the foundational principle for the interconnection between art and religion is the reciprocity between image making and meaning, a connection similar to a creative correspondence between the human and the spiritual. The actual process of making something that operates as an external mind, that is at its core a fetish, something that is inanimate but which is possessed by an idea, is something wonderful. Artists supply the world with things to think with, special tools that are magical in that we embed within these things triggers for possibilities, we provide the grit around which, pearl like, ideas may form in other minds.

The art educator also needs to help provide a safe but also transformational space for students to operate within. This has become harder to do since covid. I am aware that some students no longer see the studio as a safe space. In communal spaces other people become threats, their bodies potentially hosting invisible microbes and for those that see life in this way, daily existence becomes a constant battle against unseen menaces. Maslow's 'Hierarchy of Needs' is something all would be educators are introduced to in the early stages of any educational qualification; you are taught that every person has unique capabilities and has the possibility to move towards a level of self-actualisation. Unfortunately, educational progress is often disrupted by a failure to meet basic needs. Life experiences often causing an individual to become stuck and recently life seems to have thrown up a complicated mess of experiences, designed to unsettle and undermine the confidence of many would be learners. Therefore as an educator, I have to believe that I can help provide a safe space for thinking, one that can offer sustenance in times of unease, as well as provide information upon which someone can build their own educational pathway. One aspect of this is, as Amiko Matsuo puts it, to offer a series of connections to others working in the field, hopefully at least one of which will work for you, ring true and make sense. Each of these blog posts you could therefore think of as a possible connection to an idea or a person or to a way of working; lifelines stretched out between things, that anyone can also connect to. Remember, every journey, no matter how long, begins with the placing of just one step in front of another, but sometimes you need a shoulder to lean on if you are to take that next step and that perhaps is the best anyone can offer.

But back to Otobong Nkanga, and my role as an art educator. There are always questions. How should I introduce her work? It feels important to state that she is from Nigeria and that she mainly works out of Belgium. An image like 'Search' of course makes us think that she is searching for something. This image of a human has a building sitting on top her, a construction that obscures her identity from the observer. This is a giant figure, that stands on one world whilst pointing to another. Is the presumption that this figure is a 'she' the right one? How much of a story do I need to initiate before there is enough of a narrative to help others begin their own interpretation? How much do I need to say? That her feet have sunk down into the ground on which she stands? That white lightening surrounds a newly discovered or revealed other world? That the fact that these are woven textiles creates a very important contextual reading to them? She in many ways brings together the textile making practices of West Africa and Belgium, but what does that mean? Or is it enough to simply show an image of her work? By putting her name into this blog's index, have I given her enough status to be worthwhile investigating by you as a student or follower of this blog? Otobong Nkanga is one more artist to add to a growing list, that has come to represent a world wide movement of artists emerging from what were at one time called 'Third World' countries. The old Western art canon has been challenged and we are all asked to redefine what we think contemporary practice is. Not just educators, but museums and art galleries have been required to re-think what their existing or historical curriculums, collections and curatorial strategies represent. As this process goes into action, there will of course be a time of debate, confusion and difficulty, especially for students entering into what was one type of culture and set of established art practices and which is rapidly having to re-define itself. An exciting time, but one full of hidden and very visible dangers. It doesn't seem long ago to myself, that German artists were forced to decide whether or not their art stood for Hitler's National Socialist ideals or whether it was unfit and impure and thus subject to be being ridiculed and burnt. As new and much wider cultural forms enter into contemporary art practice, I hear rumblings and critiques, such as the way that the word 'woke' is now used. Once meaning 'being conscious of racial discrimination in society and other forms of oppression and injustice'. It is now becoming used in a disparaging way, referring to a type of overly liberal progressive orthodoxy, especially one promoting inclusive policies or ideologies that welcome or embrace ethnic, racial, or sexual minorities. This standpoint has led to Brexit, a fear of immigration, a rise of far right politics and a stance that has argued that the new Global orientation of society does not understand or recognise the importance of older more local or national cultural values, which it is further argued, many people still believe in and therefore find it difficult to accommodate or even acknowledge sets of cultural values that have come from other parts of the world or which have emerged in order to acknowledge various struggles with identity. This is a situation many seek to use as a lever for their own political gain. However we must always remember:

"Wherever they burn books, they will in the end burn human beings too". Heinrich Heine

I would never underestimate the power of fear. Change brings with it elevation and new status for some, but always loss of status and fear of redundancy for others. When this happens it is fertile ground for the rise of fascism, and it is instructive to look carefully at why during the 1920s and 30s many people across Europe in their yearning for national unity and strong leadership, turned to an idea that would lay the blame on others for collective economic and spiritual problems; a climate of blame that would eventually lead to the Holocaust. This is why the development of intellectual and spiritual nourishment for all and not just some, should be the key factor when looking at what role art and artists should be undertaking in the future. Above all as an educator I would like to remind the people I work with, that at times we seem to collectively fall morally asleep and that education can help people to wake up from that sleep and support society as a whole in the devising of ways to live, especially approaches to life that accept and value the lives and cultures of others. Teaching art is about far more than art education, it is about looking and as we learn to look we need to take off the social media blinkers and learn to see what is actually going on in front of us. It is also a celebration of the power of speculative futures, of creative possibility and the need to continue playing, especially as we become adults and most of all it can be reminder of the joy of seeing something new and fresh for the first time.

References

Laing, O (2021) Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency Dublin: Picador

Laing writes for Frieze magazine and is a long running contributor to current debates as to why art matters. By writing across the various art disciplines she makes it very clear that art as it is now experienced is a multi-platform discipline and that sometimes it is the written word that makes most sense and at other times moving images and then at other times static ones. Above all, art for her demonstrates that there are alternative possibilities and that the moments of contemplation that the arts give to us, are much too important to the health of our internal lives for us to ever give them up.

See also: