I've pointed out the relationship between the world of comic book art and contemporary fine art drawing several times, but one crossover I haven't brought to everyone's attention is the world of abstract comics. The comic book world has heavily influenced contemporary practice, Raymond Pettibon's work in particular being a clear example of an artist moving from one world into another, his early work for Black Flag being the springboard for his gallery images.

Raymond Pettibon

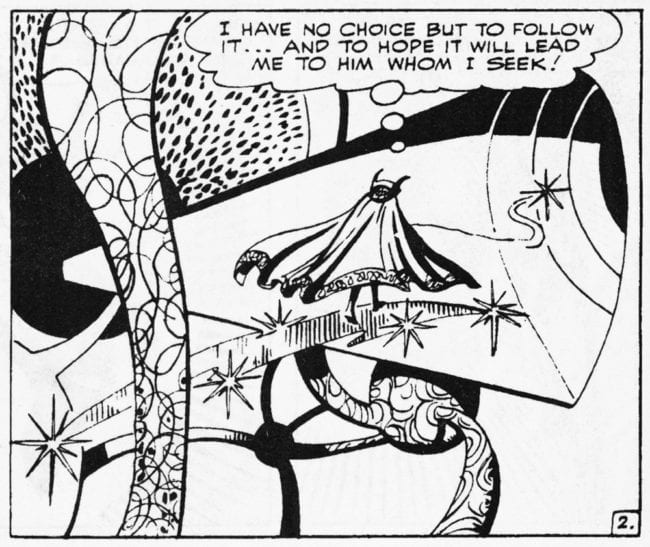

Steve Ditko: Doctor Strange

In 1963 Steve Ditko co-created Doctor Strange. In the comic he developed a series of 'mystic worlds' for Doctor Strange to inhabit. These worlds were pictured as surreal abstract universes, biomorphic forms were rendered in comic book style, using a series of formulas not that dissimilar to those described by Alfred H. Barr, who in the catalogue for the the Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition of 1936 at MoMA defined biomorphic abstract art as, “Curvilinear rather than rectilinear, decorative rather than structural and romantic rather than classical in its exaltation of mystical, the spontaneous and the irrational.” Barr had come up with 'biomorphism' to explain the nature of a certain type of abstraction, such as that made by Yves Tanguy, Matta and Miró.

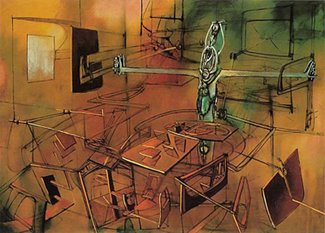

Yves Tanguy

I can remember collecting the Ditko illustrated issues of Doctor Strange as they came out in the mid 1960s and clearly seeing a link between the mystic universes being portrayed and the work of artists like Tanguy and Matta. Ditko's images were also influenced by the psychedelic art of the time, an art form that was as influential in France as it was in the States and the UK.

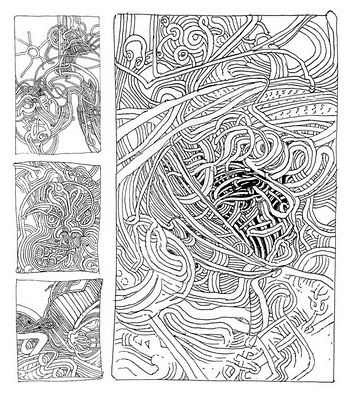

It was the French graphic novelist Moebius, in his attempts to push the abstract language of his cartoon strips further and further into his own personal graphic language, that was perhaps one of the first cartoon artists to undertake totally abstract sequences as part of his visual narratives.

Moebius: Chaos, 1991

Abstract comics tend to highlight the formal mechanisms that underlie all comics. For instance the relationship between image and word is highlighted in Gary Panter's 'Zomoid'.

Gary Panter: Zomoid

Zomoid takes us into the expressionist world of manic markmaking. Like Ditko's Strange backgrounds, Panter's world is one made from a graphic language but this time one dependent on the languages of expressionism, such as that used by Lovis Corinth or Rainer Fetting.

Lovis Corinth

Rainer Fetting 1984 Wolf

Zomoid is still however grounded in text but in Lewis Trondheim's 'Bleu' we have blobs and dots passing, intersecting, overlapping, and transforming on a blue background (the paper itself is a bright blue), a very extreme example of abstraction in a comic format, and one that owes a lot to Miró as an early pioneer of biomorphic abstraction.

Lewis Trondheim's 'Bleu'

Like other artists, cartoonists, when they sit down to create, wrestle with form, whether consciously or not: they have to be aware of the page (or screen) ratio where their work will eventually appear; they tend to use grids of panels to give structure and flow to their pages; they make decisions about what kind of marks they will make, they think a lot about gutters: all of these choices have an impact on the mood, rhythm, and content of their work.

In France there is a long history of artists responding to formal issues related to the constraints of a particular media; for instance the group 'Oulipo', short for 'Ouvroir de littérature potentielle' or "workshop of potential literature", often written OuLiPo, which is a loose gathering of (mainly) French-speaking writers and mathematicians who seek to create works using constrained writing techniques. My favourite is 'A Void' by Georges Perec, which is a 300-page novel written in 1969 entirely without using the letter 'E', an exercise following typical Oulipo constraints.

Oubapo, another French group, founded in 1992, focuses on the inherent format restrictions of making comic books. The way they do that is by adding even more arbitrary rules and structures that artists can follow in order to make new comics. Workshop for Potential Comics is in fact a sanctioned offshoot of Oulipo, part of an ever-growing list of "ou-X-pos" ranging from Oupolipo (Workshop for Potential Crime Novels) to Oucuipo (Workshop for Potential Cooking). Oubapo, however, is arguably the most active and increasingly visible of these groups. The setting of rules within which to invent and explore possibilities is something many of us have done in the past, mainly just to see how inventive we can be, but it is a system that has also been used to explore the edges and limitations of art forms and as such can be used to rattle the cages of any establishment that thinks it can run the rule over any creative oeuvre that they feel sits beneath or under their remit.

From 'OuPi' volume 5

Peter Deligdisch or Peter Draws as he is more often known on line is another abstract comic maker, in his case it is more about an obsessive need to cover a page with a constantly evolving biomorphic imagery but my own favourite abstract comic is 'Garden' by Yuichi Yokoyama. It is perhaps not abstract enough for Molotiu's anthology, but the thing about abstraction is there are no rules that state how much has to be abstracted from reality in order for abstraction to be realised.

Contemporary abstract comics continue to be produced.

Universe A: Andrei Molotiu

In fact Andrei Molotiu is the author of the key academic text on this; Abstract Comics: The Anthology (Fantagraphics Books, 2009) and if you want a proper academic history of this area this would be where to begin.

Peter Draws

Peter Deligdisch or Peter Draws as he is more often known on line is another abstract comic maker, in his case it is more about an obsessive need to cover a page with a constantly evolving biomorphic imagery but my own favourite abstract comic is 'Garden' by Yuichi Yokoyama. It is perhaps not abstract enough for Molotiu's anthology, but the thing about abstraction is there are no rules that state how much has to be abstracted from reality in order for abstraction to be realised.

Strange characters step into a garden on the first page, they are visually abstracted themselves and appear to be wearing masks, so we are in many ways prepared for an entry into an Alice in Wonderland type world as they move through a gap from one space into another. (Remember you are reading from right to left, this is a Japanese art form)

Yuichi Yokoyama's 'Garden'

Entering Yuichi Yokoyama's 'Garden' is very like dropping into Dante's 'Inferno', or being in a comic book version of Borges' 'Library of Babel'. Like the characters you don't know what's going on as you pass through different levels. Once you step into this world, you are having to work within its conventions and they are conventions that you sort of get intuitively, but never quite understand. Why is the moss actually artificial grass, why are rocks on castors? Internal barriers constantly move, strange shaped openings appear at random and suggest an earlier party of travellers have left some doors open. Sometimes we are travelling underwater, at another time we are in a library, a library where some books are stored open, others packed into abstract shapes that prevent them from being pulled out from the shelves. On one shelf we find a book of cliffs and we realise that the library is itself a cliff edge. The characters at one point think they are invited to build their own world, there is a space for materials, paper, various pipes, flags and fabrics but they quickly realise they are in a photographic reality where nothing substantial really exists; even time itself, is found to be a construction of the darkroom.

Yokoyama's 'Garden' stands several tests as a work of art in its own right. It has an integrity about itself that means that you don't need to step outside of this world in order to evaluate it, i.e. it has an internal formal consistency. It also leaves you slightly disorientated for a while, a sign that your brain has begun to operate differently and is making decisions based on 'inhabiting' an alternative world and it is now taking time to readjust to day to day reality.

The world of graphic novels and comic book art has more recently begun to overlap with the world of film. Initially because the superhero comics of Marvel and DC were very popular franchises, but also because comic and film storyboards have a narrative and structural similarity, that suggest possible crossovers.

Harry Everett Smith

If you are interested in that crossover space between abstract art and other media besides painting and sculpture, it is a good idea to watch Keith Griffiths' film, Abstract Cinema, which includes interviews with Stan Brakhage, Jules Engel, Malcolm le Grice and Len Lye. The abstract film work of Harry Everett Smith is also interesting, his work from the 1960s and earlier suggesting that he was influenced by comic/collage cutup techniques, another aspect of the psychedelic art of the 1960s, as well as influences from what was called in the 1960s the 'Expanded Cinema', when artists began interacting with cinema as a much more sculptural medium. Scott Bartlett's work being typical of the type of abstract film making that was done during the late 60s early 70s.

Scott Bartlett: Off On

A contemporary artist dealing with these issues in video is Takeshi Murata, whose 'Untitled (Pink Dot)' transforms footage from the 1982 Sylvester Stallone film 'Rambo: First Blood' into an electronic abstraction.

I seem to have wondered off track again and have ended up commenting on the expanded forms of cinema that grew out of 1960s counter culture. However there are always cross overs between art forms and I have personally always been suspicious about media specificity, especially in the Greenbergian sense; sometimes you need to push ideas out into different media just to see how they will travel. So if making a drawing on paper, why not see if it could be animated, test out whether or not it could be a template for a sculpture, or perhaps a score for music or dance; as artists we are hard wired to deal in possibilities.

See also: