In the mid 15th century Alberti published his treatise on sculpture, in this manual for sculptors he proposed that the beginnings of sculpture lay in the moment when someone came across a gnarly old tree trunk or lump of clay, the contours of which suggested something else, such as a face or an animal and that together with a realisation that the wood or clay could be further shaped to enhance this vision, an idea of art was born; an idea that placed mimesis and simile at the core of what art should be about. Nature is seen to be a sort of repository of visual ideas and the artist's job is to release them from the chaos of everythingness. A more recent understanding of this would be that human beings are prone to a psychological condition called 'apophenia', a tendency to perceive connections and meaning between unrelated things. A term that I feel was invented by a scientist rather than an artist, because the fact that things look similar is clearly a demonstration that they could be related and in nature the fact that one thing can look like another is often used to great effect. Consider the bee orchid.

Bee orchid

Justinus Kerner came up with something he called Klecksography or the art of making images from inkblots, back in the mid 19th century, an idea that would very soon afterwards be picked up by Rorschach, who used the method to begin an exploration of the hidden thoughts of his patients. However Kerner, like so many artists before him, wanted to use these random but not random shapes to generate visual ideas. In particular because these ink blots are produced by folding a paper in half they are always bi-laterally symmetrical, a factor that would immediately create a visual connection to a wide range of animals, in particular to those that had found this type of symmetry a useful survival mechanism, the fold creating a visual and structural backbone for his blots.

Kerner used Klecksography to generate ideas for poetry as well as visual fantasy.

Justinus Kerner Klecksographie 1890 Ink on paper

One way to think about Kerner's 'Klecksographie' is that he is returning these stains and blots back into the teaming pool of his own subconscious. The resulting images then open a non conscious channel from from one mind to another. These 'creatures of chance' as he called them were a product of a wider Romantic obsession with such things as Spritualism and Kerner stated that he thought these images came from 'the other world'. Blotto was also a popular parlor game in the 19th century. Players would make up stories or poems based on inkblots that they would either create themselves or purchase commercially, a fact that demonstrates another interesting feature of human nature. Things that are popular often produce a range of approaches, from the scientific, (Rorschach) via the artistic (Kerner) through to everyday usage (Blotto). The fact that this idea was probably originated by Homo sapiens during neolithic times, (some of the earliest rock art looks as if it was suggested by the forms the rock already had before shaping by people 40,000 years ago) and by animal and plant species from time immemorial (the spots on a leopard look like dappled shadows in a sun lit forest, a stick insect look like a twig), doesn't seem to worry either Rorschach or Kerner and like so many artists, scientists and academics before and since, they try to make a claim for originality that is plainly just one of those algorithms that works*.

Victor Hugo the great French novelist was another person fascinated by the power of the blot or stain to stimulate the imagination. His friend Philippe Burty had this to say about the way he went about stimulating visual ideas, ‘Any means would do for him – the dregs of a cup of coffee tossed on old laid paper, the dregs of an inkwell tossed on notepaper, spread with his fingers, sponged up, dried, then taken up with a thick brush or a fine one… Sometimes the ink would bleed though the notepaper, and so on the reverse another vague drawing was born.’

Victor Hugo Octopus with the initials V.H 1866 Pen and ink wash on paper

More contemporary artists have again returned to the idea and each time they do there is a another twist in meaning, our obsession for originality ensuring that someone will point out what is unique about this return to an old idea.

Warhol: Gold inkblot painting

Helen Frankenthaler

In a catalogue of an important exhibition of her work at MOMA Frankenthaler in thinking about the public reception of one of her paintings remembers that "at the time, the painting looked to many people like a large paint rag, casually accidental and incomplete." The catalogue goes on to explain that public reception over time changed and that eventually her work was seen to be as Nigel Gosling's review of an exhibition stated... "abstract but not empty or clinical, free but orderly, lively but intensely relaxed and peaceful … They are vaguely feminine in the way water is feminine – dissolving and instinctive, and on an enveloping scale." Although not a feminist, Frankenthaler would be eventually claimed by Feminist writers as a sort of precursor of Feminist painterly ideas, the theoretical reception of her work changing as society's understanding of itself changed. In many ways the stains and blots that make up her work becoming a field within which different theorists could 'see' different positions or ideas about the nature of what painting is. 'Apophenia' it could be argued is as ripe amongst critics as it it is amongst artists.

Rosalind E. Krauss in her essay 'Carnal Knowledge' suggested that Warhol's Rorschach paintings are parodies of abstract art and that they remind us that "there is no form so 'innocent' (or abstract) that it can ever avoid the corruption of a pejorative interpretation." I.e. that we will always see things in abstract paintings, just as we will see faces in clouds or burnt toast. The condition now known as "face pareidolia" another variation of apophenia, leading many of us to do this and on a regular basis. It is though interesting that Krauss sees this as a form of corruption and that the sexual nature of these issues further 'defiles' the purity of the artist's intention. This feels similar to the 'marked goods' syndrome, once again someone is seeking purity, but the world is like sex messy and it is out of the mess that new things arise.

Cornelia Parker is very aware of these issues and in her Pornographic Drawings from 1996, she reminds us of the Rorschach ink blot’s underlying erotic charge. She makes bilateral phallic shapes (i. e. carefully controlled images, and not random forms) using an ink made by dissolving confiscated pornographic videotapes in a powerful solvent. In doing this she reflects on the nature of ink blot making and suggests they are not chance forms, as well as making us confront our obsession with sex.

The fact that underlying sexual issues have often been associated with a psychological understanding of Rorschach ink blots brings me to another reading of them as stains, stains that we associate with bodily fluids; blood, urine, feces, semen, mucus, pus and tears. Usually these types of stains are associated with 'the abject', and are seen as repulsive and disgusting, as we eject these fluids from our body, our embodied mind uses the process as the starting point for metaphor, therefore we associate these ejections of 'bad fluids' with a cleansing and the removal of contamination. Kristeva used this concept to show how xenophobia and anti-Semitism can be aspects of the abject. What we see as things to cast out become confused in our heads, the way that Nazi anti Jewish propaganda was at times used, suggested that Jews were like a stain on society that needed to be bleached out if the German race was to remain clean. In this case we can quickly see how the idea of the stain can become politicised. However, as we can see from Frankenthaler's work, stains are also beautiful. When we look at Rose Lynn Fisher's microscope enabled photographs of tears, we see something beyond the tear stains. In these photographs the tear's dissolved salts emerge as crystalline continents and as a beautiful new language of the emotions. Her title for these images, 'the typography of tears' suggesting that we can use these images to read differences in emotions, some may be microscopic enlargements of tears of joy and others of pain or anger.

Rose Lynn Fisher: The typography of tears

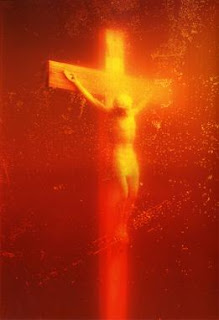

Piss Christ 1987

Andres Serrano, Blood and semen V, 1990

Detail: Grünewald's Crucifixion

Hermann Nitsch: Blood picture 1962

Hermann Nitsch stated this in relation to his work; ‘I took cloth, wetted it with blood as well as pouring blood over it, then I fixed it on canvas’. The use of blood in this case suggesting some form of sacrifice. His work was ritualistic and reflected his awareness of how religious sacrifice was meant to provide a moment of spiritual communication between God and humankind. Your blood in some societies represented your soul, therefore to sign in blood often signified that someone had made a contract with the devil. Blood as a stain is in some stories indelible, as in Macbeth, where even the ocean couldn't wash his hands clean of the stain. A stain that would eventually spread into people's minds. Hands stained with blood continue to not only inhabit art but unfortunately life as well. The cartoonist Akram Raslan died under torture in Syria for trying to make visual his fears for his country under president Assad.

Akram Raslan

Portia Munson

Blood can of course signify many things and for women the monthly menstrual cycle is vital to an awareness of their own fertility. Portia Munson made menstrual prints every month for 8 years. She made the prints by pressing sheets of paper against her body during the time she was menstruating. Around each print Munson would inscribe a text of both personal and historical narratives about menstruation and menstrual rites. Once again a stain carries the information, however for Munson these stains also resembled creatures like angels, birds, or bats, the starting points for new narratives, stories that have fellow travellers such as Angela Carter or Kikki Smith.

Juanita McNeely is an artist that took the difficult decision to make paintings about her experience of abortion back in the 1960s. Hard to confront and difficult subject matter is rarely commercial, so her work for many years remained undervalued. In her work paint itself bears the stain of the document and her approach opens yet another reading into what we mean by the art of blood, sweat, and tears.

Juanita McNeely: Is this real?

*just one of those algorithms that works.

I came across the following definition of an algorithm in Yuval Noah Harari's 'Homo Deus'.

'An algorithm is a methodical set of steps that can be used to make calculations, resolve problems and reach decisions'. p.97

Humans are in effect therefore a type of algorithm. 'The algorithms controlling humans work through sensations, emotions and thoughts. And exactly the same kind of algorithms control pigs, baboons, otters and chickens. Consider for example the following survival problem: a baboon spots some bananas hanging in a tree, but also notices a lion lurking nearby. Should the baboon risk his life for those bananas?' p. 99

The calculations that the baboon will make in the split second of a decision making process will if correct ensure its survival. If the baboon is too cautious he will not eat, and if he is too impetuous he could be eaten by the lion. A baboon that gets it right more times than gets it wrong is more likely to pass its genes on, therefore it will as a creature over time develop a very finely adjusted internal choice making algorithm. Harari goes into great detail as to how this works and it helped me to understand why I sometimes prioritise my emotional responses to life over my more rational ones.

See also:

Monoprint as a drawing process and how to respond to seeing shapes in the ink

Frottage and photography

Resemblance mimesis and communication

Using pigments suspended in water which is what stains usually consist of

Where stains and traces meet

Fabulous Content.

ReplyDeleteShop Drawings Preparation in USA