The idea of the proscenium arch can be thought of as a social construct that divides the actors and their stage-world from the audience. In fact the seat that would be the perfect point from which to view the action, was often both the place where the person most powerful present would be seated and the spot opposite the controlling perspectival vanishing point. The curtain usually comes down just behind the proscenium arch, both hiding the stage from view when scenery is changed, but also reminding the audience of the reality that surrounds the illusion.

Because this type of stage fits the mathematical model of perspective, it also becomes very easy to use the various tricks of anamorphic perspective drawing to create further illusions. Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza exhibits an early use of anamorphic perspective, the illusion that the street is much longer than it really is, is created by a forced perspective. Forced perspective is a technique perhaps seen at its clearest in the Palazzo Spada, as created by Francesco Borromini. He designed a barrel-vaulted colonnade that looks much longer than it is by making the two sides of the colonnade converge and by reducing the height of the columns as they recede.

It is Watteau that brings the two traditions of visual art and theatre together again. I have posted about him recently because Watteau as a painter was someone who could deal with the visualisation of a society in a transitional state and I strongly believe that our society is also in a similar position. The people he depicts are set into liminal spaces and the space of the theatre is typical, as it sits between worlds. It is on the one hand 'real' as the actors and the stage are physically clearly in existence, but on the other hand it is an imaginary space, one that can be used to literally play out ideas. The relationships between people in Watteau's paintings and drawings are suggested by small gestures and body postures and you get the feeling that people's minds are suffused by a never ending series of unresolved actions and unfulfilled desires. They act out their lives but perhaps have forgotten their lines. You sense that the people in his paintings have lost direction, that they are unsure about the roles they should be playing and in compensation they turn to the Commedia Dell’Arte players who all know their roles and play them to perfection, day in, day out, to audiences across Europe.

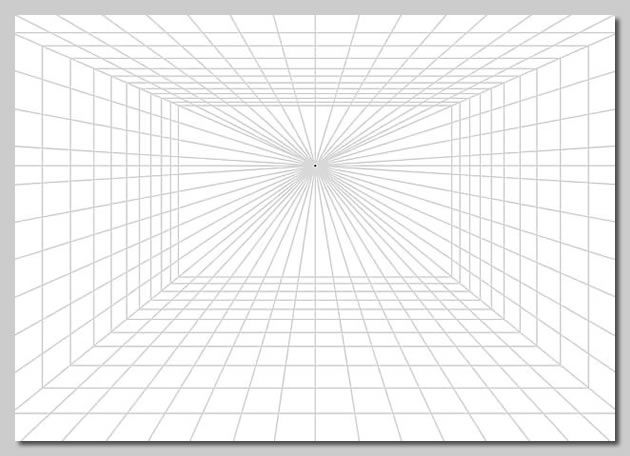

Because of this understanding of theatre type perspectives being ones within which you can play out an idea, artists still use these one point perspective stage like spaces. Kiefer's large charcoal drawing on canvas, 'Deutschlands Geisteshelden' positions the viewer as if they are looking through a proscenium arch at a stage. Burning torches line the walls of a space that is empty except for the names of the actors scrawled above the fast receding, single point perspective floor. These actors (or actants) are German cultural heroes; Joseph Beuys, Arnold Böcklin, Adalbert Stifter, Caspar David Friedrich, Theodor Storm, and others. These are the actors of a painful history play and Kiefer sets out his image as a stage, so that he can make them perform as ghosts of their former selves. All are dead, Joseph Beuys, his mentor dying in 1986, just before Kiefer began drawing out the image. Kiefer I'm sure was well aware of the relationship between images made using one point perspective and the theatre, he is a well read artist and he cites many literary figures as past influences on German culture. The image as a stage whereby ideas are acted out continues to be a powerful idea and as more performative ways of working have emerged out of traditional drawing practices, I would suggest that the fusion of drawing and theatre is something that will become more and more the norm.

Life or theatre

No comments:

Post a Comment