I'm looking at mathematics again, so apologies for this, but in an attempt to maintain a holistic approach to aesthetic thinking, every now and again I try to dip my toes into waters I'm deeply frightened of. In this case it's the work of Michael Hansmeyer that I'd like to highlight. This is work that uses layer upon layer of flat drawings, that when cut out of card and stacked one above the other make complex three dimensional shapes that bridge the gap between sculptural form and drawing.

Hansmeyer often uses a finite subdivision rule as a way of repeatedly dividing a two-dimensional shape into smaller and smaller pieces. Subdivision rules in a sense are generalisations of regular geometric fractals, but instead of repeating exactly the same design over and over, they have slight variations in each stage, and this makes for a much richer structure while still maintaining an overall harmonisation of forms. These subdivision rules are often found in biologic entities, which is why structures using this way of constructing themselves remind you of natural forms.

A finite subdivision rule applied to a polygon

Using flat forms to construct three dimensional models

As you divide regular geometric forms and you move away from symmetry you begin to achieve a nature like complexity, a complexity that can be stabilised formally by reintroducing bi-lateral symmetry.

Two symmetrical rotations of 'time' section above

A complex made of four quadrilaterals subdivided twice.

Our lungs obey a similar principle, and the reason I've become more interested in these things is that I've been thinking more about how to envisage the things we don't normally see, such as the insides of our bodies.

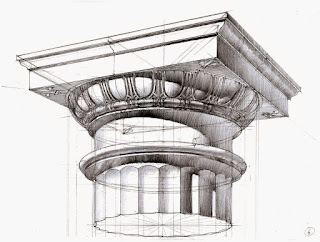

Grotesque columns based on Doric forms

Hansmeyer applies these types of rules to create variations on regular patterns. In the case of his columns above, an abstracted doric column was used as the input data to the subdivision processes. The ornamentation is developed by controlled subdivision put together as a continuous flow. The complexity of each column is a result of changing focus on different aspects of the data input. For instance one section might be a response to the dimensions of the indentations that surround the capital, and the adjoining section could be a response to the change from a circular cross section to a square one.

Once the flow of change has been established, drawings are made of each move and these are then used to drive a laser cutter.

Cutting and building a column out of cardboard sheets.

I have mentioned Michael Hansmeyer's work before, but have been returning to it, to think about its generative processes of arrival and how my own process of making variations of form relates to it. Generative mathematical form does seem to be a powerful tool and has a deep connection with the way many forms in nature are generated with slight variations, such as human beings. In order to see if there was an entry point for someone as mathematically challenged as myself I have done a little research and it would seem that '

Grasshopper' is the best software to begin with. It requires no knowledge of programming or scripting, and it can help you as an artist beginning to look at this area to build your own form generators. So if you are interested in this area, don't be put off by its apparent complexity, like most complex things, it is built from simple units. You do however need to understand what a Rhino environment is.

Rhino 3D is a free form surface modeller that uses a modelling by curves technique or NURBS (Which I did look at a little while ago) The fact that it is still free to download does mean you can make a start on this without having to buy expensive software.

More recently Hansmeyer has been using these design principles to create set designs for opera. His grotto for Mozart's Magic Flute, being a particularly successful transfer of his more sculptural ideas into operatic stage design. Not long ago I put up a post on artists, such as David Hockney, using their skills to create grand dramatic and expressionist spaces, in this case a sculptural principle now becomes a shaper of environments and it also further illustrates a point that I have been making more and more recently. Visual thinkers can move between being seen as artists, biologists, architects, or stage designers, because essentially they are problem solvers. Fine art students are just as capable of solving visual problems as students from any other discipline, with the added bonus that as an artist the problems that you set for yourself are just that, self set problems, arriving out of issues and interests that you are fascinated by.

Michael Hansmeyer's set for the Magic Flute

This work is a form of digital morphogenesis, a type of generative art in which complex shape development is enabled by computation. Perhaps the most interesting issue is though that you can find the same formal principles of shape morphogenesis in biology, geology and geomorphology, which for myself raises an issue about the divide between organic and inorganic matter. The more that I am drawn to animism as a way of acknowledging the rest of the world that isn't me, the more I see similarities between the way matter morphs into form and the way life forms are shaped, it is perhaps more an issue of one taking longer than the other to become what it becomes. I am making a series of drawings that are meant to sit visually in that space between the organic and the inorganic, that are images of inner body sensations, feelings and awarenesses and I am thinking about how to explore their formal possibilities further, which is also why I'm personally becoming interested in shape morphogenesis.

On becoming aware of loss

The smell of fear

No comments:

Post a Comment