Anatomy of a firework

The first fireworks were made from what was known as black powder packed into long, narrow bamboo tubes. The resulting boom was thought to scare away evil spirits. Black powder was invented in China over 1000 years ago, and is a type of gunpowder made from 75% potassium nitrate (saltpeter), 15% charcoal and 10% sulphur.

The Blastula

In mammals, after fertilisation the egg evolves; the cells in the blastula arrange themselves in two layers: an inner cell mass (the embryoblast) and an outer ring (the trophoblast). The inner cell mass will eventually form the embryo. At this stage of development, the embryoblast consists of embryonic stem cells that will differentiate into the different cell types needed by the organism. The trophoblast will contribute to the placenta and nourish the embryo. In a firework there is also a need to protect the components that will be brought together to form an inorganic life. In the case of a mortar, a firework designed to project burning stars into the air, the shell, often in the form of a paper sphere, is what holds everything in place and carries the ingredients of 'life'. The sphere is usually packed as two halves. The top half is filled with stars, (small pellets made of chemicals, such as powdered metal salts) pellets designed to produce specific effects once the mortar has launched them into the sky. The bottom of the shell contains a lift charge that blasts the shell out of the mortar.

The mortar's internal paper sphere could be thought of as its 'stomach'. Humans have a dark unseen interior stomach that at times can become explosive too. When we suffer from diarrhoea the contractions of our bowels become stronger and more forceful because of an overfull rectum; a state often accompanied by the production and loud explosive ejection of large amounts of gas. We make objects that are extensions of ourselves, our embodied mind thinks of ideas in particular ways and its thought processes are reflections of what it is most deeply aware of; the workings of the body it inhabits. In my research into the visualisation of interoception, some of the images used to visualise pain are also rather like fireworks seen in the dark.

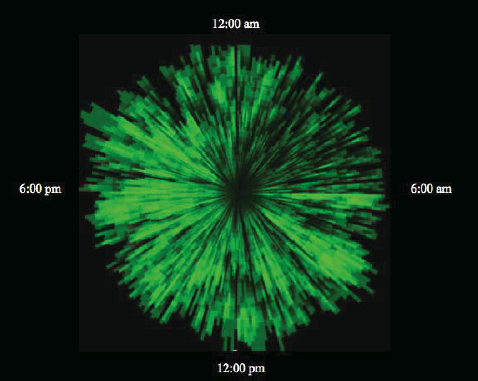

Computer generated 'Jellyfish' Chronic Pain Metaphors. Dr. Xin Tong

Pain data visualisation as a circular map: Dr. Xin Tong

A representation of an explosion

Of course, many of the explosions that would have been seen, were the result of gunpowder and except for those involved in war, it would be when watching firework displays that most people developed their mental images of coloured lights exploding into darkness. The idea of the aerial shell firework was developed in Italy and it involved complex chemical research into which elements would be needed to be burnt if fireworks were to have particular colours. We now understand how this works. Different chemicals react with fire to produce different coloured flames, because the electrons moving

around the nucleus of each element have different energy levels. When heated, the electrons get excited

and move to a different orbit and as they cool down they move back to their normal orbit and this extra

energy produces light waves. Each element has different amounts of extra energy, therefore the emitted light waves use different wavelengths hence we see different

colours. However at the time when this was first observed, chemistry was still emerging out of its long association with alchemy and the colours that emerged were often seen as being almost magical. These are the most commonly used firework colours and their associated elements:

White: titanium, magnesium, beryllium, aluminum

Red: strontium (for an intense red), lithium (for a more medium red)

Orange: calcium

Gold: charcoal, iron, lampback

Yellow: sodium

Green: barium

Blue: copper

Indigo: cesium

Violet: potassium, rubidium

Once he has an idea of the graphic nature of the next stage, stencils are cut and joined together so that a template is made that operates as a mask. This is laid over a bare canvas, as you can see from the image of the stencil's shadow that is cast as it it lowered down.

Cai Guo-Qiag: A firework blossom: Philadelphia Museum of Art

White: titanium, magnesium, beryllium, aluminum

Red: strontium (for an intense red), lithium (for a more medium red)

Orange: calcium

Gold: charcoal, iron, lampback

Yellow: sodium

Green: barium

Blue: copper

Indigo: cesium

Violet: potassium, rubidium

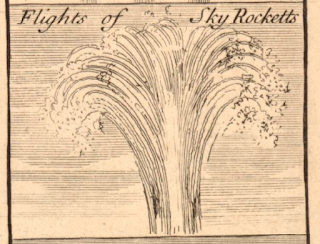

18th century royal firework display: Etching

Back in the 18th century fireworks already had a standard set of presentation forms. If you look at the images on either side of the etching above of a royal firework display, you can see clearly set out their various configurations. It is interesting to compare these drawings to our present day descriptions of firework forms. How they are drawn immediately suggests a firework/flower visual connection but there are several other similes that have evolved over time.

This 'Vertical sun' could also be a sunflower. It's fascinating to look at this image and compare it with Matthaeus Merien's of a sunflower; he loads his drawn image with stars, suggesting the sunflower's affinity not just with the sun, but with all stars.

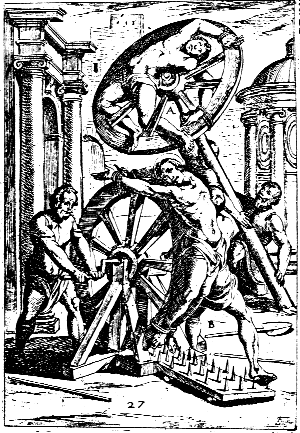

Catherine Wheel when lit

What was in the 18th century known as the Vertical Wheel is now usually know as a Catherine Wheel. It was historically a form of torture also known as a 'Breaking Wheel'. Amongst several other death threats and actual torture, St Catherine was supposed to have been condemned to death on a spiked breaking wheel. But in a rapidly evolving non-Christian society, I suspect fewer and fewer people will make the connection with the spinning spectacle of a revolving firework and a saint's martyrdom.

What was called a 'Fruitoni' could possibly have been modelled upon the pineapple, which had been known in Europe since the time of Christopher Columbus, who brought some back to Spain in 1493 and which was in the 18th century grown in greenhouses in many Royal Gardens throughout Europe.

Flower jars

I'm presuming that 'Pots de brin' would be translated into English as 'Flower jars'. Considering fireworks were initially used to scare away ghosts, the fact that they can now be seen as representations of flowers, shows how far the metaphorical range of any one medium can spread.

The shapes of contemporary fireworks are also often named after flowers and other natural forms. It is interesting to compare them and to think about how different likenesses can be found in such a variety of closely related formal principles. Fireworks can of course be experienced as loud coloured explosions, but it is also fascinating to think about how they can also be used as drawings in light to represent other things in the world such as flowers and spiders but also elements of landscapes or non representational forms.

Fireworks belong to a genre of drawings that includes neon signs, laser lines, torchlight processions, light projections and stained glass images.

My own personal favourite, perhaps because it was one of the few fireworks we were allowed to light as children, is the cone shaped fountain often called 'Mount Vesuvius' or 'Mount Etna'. This is a miniature volcano, which when you think about it is a wonderful idea. The grandeur and sublimity of one of nature's most impressive sights, compressed and made available, so that you can experience it in your own back garden. This must be art of a high order.

Various volcanos

When we were children probably one of our first and most memorable experiences of drawing in the dark was with a sparkler.

The drawn line of a sparkler

Persistence of vision means that the swing of an arm can leave the trace of an imaginary line on our brains. There is something magical about this, something that takes us back to games played around fires in the dark thousands of years ago. I'm sure many a budding artist will have tried to draw shapes in the dark with the glowing end of a stick pulled out of the fire. Drawing with light in dark spaces is a very powerful way of working.

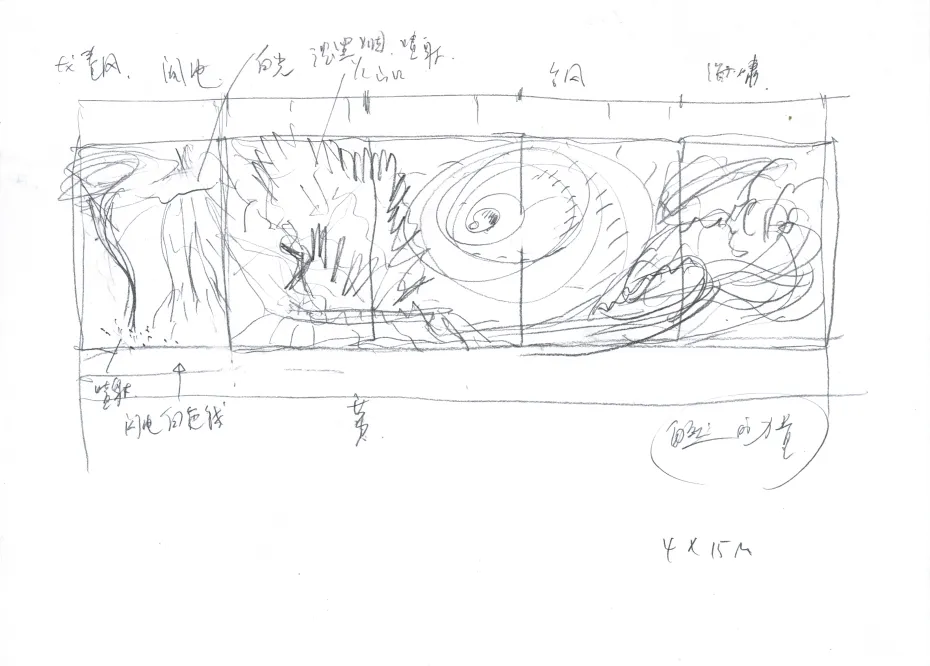

The artist Cai Guo-Qiang has for some time being associated with making drawings using gunpowder. Being Chinese he is able to appropriate China's deep firework cultural heritage, but his work is also placed firmly in the traditions of contemporary art practice, being partly performance, partly installation and partly drawing as an extended practice. He begins his ideas by drawing, as you can see in the large Sharpie drawing below, often working visuals out in public, in this case the drawing is large enough to allow him to achieve sweeping curves by swinging his arm in a circle.

Cai Guo-Qiang: Drawing made with a Sharpie for 'Chaos in Nature'

Gunpowder is poured over the stencils

The drawing is lit and it explodes into life below large sheets of cardboard.

Gunpowder is poured over the top of the huge stencil and then when everything is ready, large sheets of cardboard are taped together and laid over the whole construction. When ready, and usually with an invited audience in place, Cai Guo-Qiang will light the gunpowder and let it explode away beneath the cardboard, making lots of flash bangs and smoke, which of course everyone enjoys, as it is slightly frightening, but actually very safe.

Cai Guo-Qiag: Seasons

Cai Guo-Qiag: A firework blossom: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Cai Guo-Qiag's most iconic work is his 'Sky Ladder', a 1,650-foot-tall installation, held aloft by a giant balloon and rigged with explosives. As the installation ignites, it builds a ladder that ascends to the heavens.

It is a pity that there are now so many regulations surrounding the obtaining of gunpowder. In days gone by on the Art and Design Foundation course in Leeds we used to make solutions of saltpetre mixes and draw with them on paper, then take them outside and have an exciting session watching the now dried out lines burn across sheets of paper, sometimes of course having to throw water onto the papers to stop them burning away entirely, but it was an event, and it made everyone very aware of the specificity of this particular drawing medium. Gunpowder is as a drawing medium, just that, a medium with which you can draw. It reminds us that every medium brings with it a surrounding set of associations, both cultural and material. It is just that in this case everything is heightened and is so much more dramatic.

See also

No comments:

Post a Comment