Visual language would have started like most languages by human beings

communicating by using ideas of 'likeness'. There is a category of definitions

which are called, 'ostensive'; denoting a way of defining by direct

demonstration, e.g. pointing. I'm sure that after watching young children

learn, pointing to things to show the children they were like something

else must have been a big part of visual language development.

Because our bodies are the things we know best, I would also suggest

they were the basic initial measure. You can think in terms of body schemas,

for instance, an upright vertical body suggesting maturity, health and strength.

This could be represented by a 'right' angle, a line standing upright

vertically, can therefore also be seen as strong, healthy, in balance and

'right'. A body that is ill lies down, and in the case of dying achieves a

horizontal. As we get older we are less 'up-right', if we trip or fall we are

taken off the vertical and into the lower angles. Therefore lines approaching

the horizontal can be seen as representing being 'off-balance', ill or

approaching death.

I would suggest that the same is true of the quality of line. In full

maturity and good health we move smoothly and with confidence, when very young

our movements are jerky and unformed, and when ill or approaching death we have

shaky hands and feeble far less confident body movements. So if we make lines

that are smooth and confident we should be able to point to them and say look

these lines are like a mature strong confident person. A line made with shaky

marks, with a hesitancy could again be compared with a human being in a similar

state. It is very easy to see how a certain emotional register could therefore

be applied to the reading of drawn lines. (My earlier post on drawing

with Bezier curves relates to this, the

authority of lines drawn using vector graphic software, perhaps related to

lines drawn with a very confident and steady hand).

John Bellany: Self portrait on surviving an operation

The drawing above was done by John Bellany immediately on waking from an

operation in hospital, it's shaky lines echoing the physical and mental state

of the artist.

The attempt to codify the various elements that make up visual languages has a long on-going tradition. One that

is though very questionable once it begins to step outside of basic body

schemas. For instance if you look at the work of Eugen Peter Schwiedland

(1863-1936), an Austrian born graphologist who lived in Vienna; he

invented the Graphometer, a device like a protractor that shows how the slant

of your handwriting indicates your personality. It relies on a similar reasoning

to the one I have just introduced, but his readings are very subjective.

Look at direction 1: Schwiedland suggests that it represents

'insensibility' that the upright represents a cold reserved

nature, however as you can deduce from my suggestion that we read angle

from awareness of our own bodies, an upright style of writing could also

suggest strength of character and someone in the prime of life, a

balanced character in tune with life. One aspect of body angle I am very

aware of is that I put my body at an angle in order for me to be able to run

fast, I could therefore argue that direction 3 relates to someone who

is impatient and who wants to get on quickly. Graphology has of course

been discounted as a science because of this subjectivity, but even so

amongst graphologists the relationship between personality and angle and slope

of line would have become a shared common language and

would have been a 'true' language because it was a shared series of

conventions that could be understood in the same way by other members of the

community of language users.

The concept of directly relating angle to emotion was developed to a

fine art during the 19th century and reached such a level of sophistication

that 'aesthetic protractors' were made to help artists determine their

compositional structures. Charles Henry had argued that colour could be

used to express certain emotions and that this emotive effect could be

heightened when combined with the angle and direction of a line. He was very

influential on artists such as Seurat, who developed some of his compositional

ideas on Henry's work. (Again we have a reference to artists wanting to

underpin their work with mathematical 'rightness')

The one part of the body we spend a lot of time looking at is other people's

faces. We do this because it is via the face that a large amount of meaning is

communicated between us and a large part of this meaning is emotional. Any

comic book artist knows that in order to tell the reader what is happening

emotionally a facial close-up can do the job.

Awareness of facial expression extends and deepens the body schema and 19th century scientists were hard at work trying to formalise facial expressions as languages to be used by artists. In particular the artist Humbert de Superville wrote an essay designed to explain how gestures and facial configurations could be categorised.

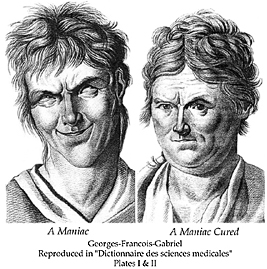

We use the term 'Physiognomy,' when describing the 'science' of the

assessment of a person's character or personality from his or her face. Compare

this before and after image.

The maniac head is tilted, hair disturbed, everything is more angular,

and when 'cured' eyes are level, the mouth is a firm, almost straight line and

we feel that all is in balance.

Perhaps the most powerful body of work on the subject belongs to the artist Messerschmidt, who developed a series of sculpted busts designed to illustrate the range of human emotions.

Basic emotional features and how to draw them

were often set out in 'how to' books on drawing.

Perhaps the most powerful body of work on the subject belongs to the artist Messerschmidt, who developed a series of sculpted busts designed to illustrate the range of human emotions.

Messerschmidt

Lithograph by Toma depicting Messerschmidt’s “Character Heads” (1839)

Superman artist Curt Swan produced model drawings that were used to show

other Superman artists how to draw Superman’s face in various emotional states.

Notice how no matter how agitated Superman is supposed to be his facial

appearance never approaches the formal disturbance of Gabriel's maniac further

above, but perhaps the most important issue for me is that because the line

drawing quality never changes, non of the expressions feel 'authentic'.

Superman comes across as a hollow cypher, he is about physical action rather

than emotional range. Compare Kent Williams' drawings of Batman, even though

Batman's face is always hidden by a mask, Williams manages to communicate the

character's internal emotional conflict by his use of line quality and dramatic

dark/light contrast.

The problem with physiognomy, is that as a species we are very good at

deceit . Because we know what works, we can simulate expressions, we know

how to use the knowing smile and can shed crocodile tears. You could argue that

the best test of whether or not someone understands a language is how good

they are at using it to lie. It is common knowledge that many comedians are deep down,

seriously distressed people, and by being able to 'put your face on' many of us can then 'face

the day'.

It is not a far stretch of the imagination to argue that Kandinsky must

have seen de Superville's diagrams when preparing his book 'From Point to Line to Plane'.

Henry stated that you could utilise a small degree of sadness in an

image by using the correct angle ratio, he also believed that his laws of

'dynamogony' held true in all the arts and that the arts were all related in

how they communicated emotion. This brings me to another way to think about

visual language, and how it could be translated; that of synesthesia, and

Kandinsky is the key figure here as he was a synesthete.

Read:

Cezanne and Modernism: The Poetics of Painting By Joyce

Medina p. 72 for text on Henry and his aesthetic protractor

You will find a image of an aesthetic protector in Seurat and the

science of painting by William Innes Homer

Download:

https://www.gadgets-personalizzati.com/

ReplyDelete