A cat's cradle

This is how an old Alaskan children's tale was told.

Begin by looping the

string over both thumbs and spread your hands apart.

A

woman sat weaving one day and as she did so, she began to hear a buzzing noise.

It went like this…bbbuuzzzzzz

Twist your left hand to

make the string wrap around the back of the hand.

The

woman looked up and saw nothing, she looked to the left and to the right and

saw nothing, so she went back to her weaving, in and out, in and out.

Swivel your right hand so

that the string is not twisted, but do not have it wrapped around the back as

you did with the left hand.

The

buzzing noise now grew louder…BBBBBUUUUZZZZZZZ and the woman looked around

again, she looked up and she looked to the left and to the right but she could

see nothing, so she went back to her weaving.

Bring your right little

finger over to left hand and use it to hook both strands of string running

between your left thumb and your index finger. Pull right your hand back and

make the string taut.

The

woman carried on with her weaving; in and out, backwards and forwards, in and out,

backwards and forwards, and she began to hum a sound of her weaving, in and

out…hum, hum…up and around…hum, hum…

Bend your left hand toward

your body and use your left little finger to hook both strands of string in the

middle of your right palm. Your hands will not be able to move far apart at

this point.

Suddenly

the buzzing grew very loud. The woman looked down at her weaving and was

surprised to see a giant mosquito right in the middle of it.

Use your right thumb and

index finger to grab string wrapped around back of left hand. Lift it over all

4 fingers on left hand and let go. (Don't let go of string wrapped on your left

little finger!) Now spread your hands apart quickly.

The

mosquito was now flying around the woman’s head, it began to buzz even louder.

It flew down and buzzed into her ears and under her chin. It flew past her eyes

and the tip of her nose. It buzzed in her hair and flew down past her cheek, it

was driving her crazy!

Move your arms up and down and wiggle your thumbs and

little fingers to make the mosquito fly.

"I

am going to catch that mosquito," said the woman. She waited and waited until the

mosquito flew right in front of her. Then she clapped her hands over it, and when she did the mosquito went quiet and

all was silence.

Hold your hands together

for a while, and then when you open your hands, relax your little fingers so that

the string will slide off of them. Do this quickly and spread your hands apart

to show that the mosquito has gone.

New Hebrides (Vanuatu) sand drawing

When I was a young boy Rolf

Harris was often on the TV. He would have a large canvas set up and would

gradually paint a scene, usually a picture that had something to do with an

Australian aboriginal story. He would always make the image in such a way that

you could never see what the picture was going to be until the last minute when

he completed the story. He would constantly ask, "Can you

tell what it is yet?". Now of course discredited because of indecent assault

charges, his early career left a lasting impression of how an image and a story

could be woven together.

Rolf Harris painting and telling a story

‘How the kangaroo got her

pouch’ was one story told by Harris, this is an old story he would have taken

from an aboriginal dreamtime tale. The Dreamtime is oral, visual, acoustic, the land itself, the

creatures that inhabit it, the customs of the tribes and all that happens in

both dreams and waking, everything locked together as a whole, in something

that is called the Dreaming. Harris took elements from this culture and like a colonial invader stealing artefacts, presented his stories to a far off alien culture, to children wanting to be entertained and distracted. But in doing so he sowed a seed, and however tenuously linked a thread of the Dreamtime to my own imagined landscapes.

String figures rely on likeness to work. Look at how the Navajo story below comes alive as you see the heads of the two coyotes facing each other, their tails caught around forefingers and their legs around thumbs. As Harris would say, "Can you tell what it is yet?".

Navajo string figures: Coyotes running opposite ways

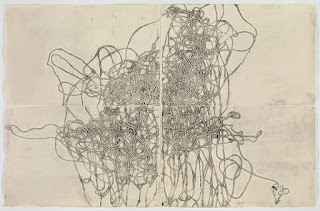

The complexity of possible connections that could be made is huge, Lillian Hsu's print below being an example of what happens when your strings get tangled and your stories get confused.

Lillian Hsu String drawing

Perhaps Hsu's print is more like life though, the way we are directed to look at knots as topographical thinking tools, is very attractive, but often unrealistic. Knots though are an important element in this story, so although for the moment I don't want to open up another strand, I will leave a couple of images as a reminder that at some point I shall develop a post on them.

Knots

Compare the clarity of the knotted forms above to the work of the Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota. Her installation 'The Key in the Hand' was a wonderful experience to walk into, when you entered you became totally lost in a mazy haze of thousands of red threads, and when you got closer to the centre of the installation you realised all these threads were connected to a boat, as if it was caught in a spider's web.

Chiharu Shiota 'The Key in the Hand'

Chiharu Shiota 'Uncertain journey'

Shiota's 'Uncertain journey', a more recent installation is less immersive but still provides a very good illustration of how intricately connected things are.

When I worked at the steelworks, we used to use chalk lines to mark out where large sheets of metal needed to be cut. A taut string covered in chalk, is a much easier thing to make than a straight edged ruler, you need no other technology than an ability to pull a string between two attached points and be able to use a piece of chalk or some ground up chalk dust to coat the string with powder. I suspect most of Euclid's geometric proofs were drawn in this way. His definition of a straight line being the shortest distance between two points, would have been so much easier to arrive at if he was pulling a string taut.

Snapping a chalk line

String is deeply embedded into geometric thinking when it is in its most practical form. The image on the cigarette card below is a crude demonstration of how to draw a curve from two fixed points and as a boy I well remember practicing drawing circles and especially ellipses, using a couple of drawing pins, a pencil and some string. I strongly suspect that all early geometry began with the making of string structures and if so, the stories and tales associated with cat's cradle type string structures would have been still hanging around and not separated out as a different type of thinking. Things would have been much more interconnected.

An early Islamic diagram by Al-Biruni of the phases of the moon.

If you look at the ancient diagram above you can almost see the 'stringing' and the text that sits alongside the drawn lines could represent the story. Modern science is little different, the image below being almost a cliched sign for scientific thinking, a type of thinking that requires a close interrelationship between mathematics and geometry. All it needs is the story around which all that abstract thinking is developed.

When Daina Taimina developed a physical way of modelling hyperbolic space, she used crochet. What was interesting about her work was that she realised that we need to touch things in order to really grasp what they actually are. Her understanding of geometry was developed using crochet so that it was much easier to understand how a line, generated by a fold, could operate in hyperbolic space. You can watch her talking about how this came about in this video. Drawing, as in geometry is vital to this understanding, but in this case it becomes clear that without the type of drawing we associate with drawing threads, she would not have been able to develop the idea.

I was again reminded of the myth of Theseus, in particular the part where Ariadne gives Theseus a ball of thread to unroll as he penetrates the labyrinth so that he will be able to find his way back out again. It is as if the thread allows him to drop down deep into his subconscious and return enlightened after defeating the minotaur. Taimina uses her thread to reveal the mysteries of hyperbolic space in a similar way. Daedalus the architect of the labyrinth, is often regarded as a prototype of the scientist inventor, the complexity of his thinking being something others could not fathom. However the implications of complex mathematics that we associate with scientific thinking can sometimes be clearly demonstrated by visualising processes, the key one being of course drawing. This PDF is downloadable and sets out the relationship between the mathematics of hyperbolic spaces and how these can be visualised using crochet.

The changing curvature of surfaces is something as artists we all have to deal with when drawing objects. See this earlier post. The mathematics of Gaussian curvature is a way of thinking about gravity affected spaces and the way that these are visualised relies heavily on the experience of artists visualising 3D form.

The saddle: An example of negative Gaussian curvature

Various possibilities of Gaussian curvature

You can see from the illustrations above why the idea of crochet was so useful when trying to make sense of these types of spaces. Crochet can also be thought of as a type of net and a net is a flexible grid; so I seem to have come full circle again, perhaps time to end this post and snip this thread and start a new one.

Uccello

See also:

Wonderful Sand art...

ReplyDeleteHow to pass Nebosh IGC3

Nebosh IGC Registration

IOSH MS course in Chennai

Nebosh Course in Chennai

Safety Courses in India