He was an early critic of the art market system and pointed out that the separation of art from popular culture, children’s art or the objects that were normally associated with ethnography or primitive art was wrong, indeed he stated that in his eyes they were often identical. As far back as1889, Kandinsky had made a visit to the Vologda governorship, coming across the Zyrjane, a Finno-Ugric population, where he met shamans and was astonished by the beauty and colours of the furnishings and artefacts that decorated their homes.

Joseph Beuys saw himself as an artist-shaman, a spiritual guide who used art to heal and transform society by connecting people to deeper, often forgotten, human and natural truths. He believed that art could be a force for social healing and when in the early 1980s I met him, he made a deep impression and helped me to find a needed belief in the power and importance of the discipline I was involved with.

However I've never been as forceful in my beliefs as Beuys, I tend to work by feeling my way towards something, rather than having a plan and executing it. For instance when I make one of my ceramic ideas, something comes into being that wasn't there before, arriving out of a muddle of thoughts and possibilities, partly as result of the material having a voice and partly out of my own desires to bring a thought into existence. Once made ceramics belong to the world of objects and many of the human made objects we engage with can also be used as commodities and even the ones initially not made as commodities, are often judged or regarded as objects that in one way or another have a relationship to commodities. Such is the power of money and exchange value. The idea that monetary value is the only way to measure worth is central to the art market and it is no surprise that the media rarely discuss art, except when it is sold at auction and fetches astronomical prices. Under Capitalism, worth has a very narrow definition and the strive towards economic success, seems to have eroded away many of our more spiritual or communal bonds and in particular in relation to the making of art or other culturally significant objects, we are loosing sight of the transformative power of objects as extended minds. However the shamanic idea that objects have fetishistic power lies not far beneath the surface of our everyday economic reality.

Marx wrote, "A commodity appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties". He saw that a belief in invisible lifelike powers existing within inanimate objects was essential to our complex meaning system that embeds the believer into the wider world of objects with meaning. Coining the term 'commodity fetishism', things were Marx believed 'magical', in that they promised 'magical' effects, that were, he would further argue 'fictional' or of no clear practical use value, but which nevertheless appeared to be the drivers for possible life changing psychological transformations. Marx never did quite get his head around the psychological power of capitalism. He took several of his ideas from contemporary writings about tribal uses of fetishes and other animist practices and it is this fact, that makes me think again about the role of the consumed object within late capitalism. I see the animist idea that underpinned Marx's original observations still in place. In recognising this, perhaps this gives us a way forward when looking for alternatives to a Capitalist model. Any alternative possibility to values based in capital, should emerge from a recognition that whatever new system comes into existence, that it would have to exercise a similar underlying psychological lever, but one that drove people into making more communally supportive decisions, rather than rewarded the economic achievements of the individual.

When I make a drawing or a ceramic object, I am not making one to sell, whereby I exchange it for cash. What I am doing is though trying to make another type of transaction, one whereby the person coming across the object is asked to think about why such a thing might exist. The art object becomes in effect a type of externalised mind, a form that allows thought to be grown around itself. The exchange value in this case depends on the receptiveness of the person encountering the object and how entangled they want to be into the possibilities the object opens for them.

For instance, in relation to a work I made a while ago now, my initial prompt to making over 300 ceramic fish was a description I came across of thousands of dead fish, washed up on a riverside beach due to an outflowing of pollution into the waters that they had previously inhabited. I wanted to ensure a moment of news was not forgotten and to make it concrete and unavoidable. I also wanted to highlight the bigger issue, which was the fact that we are constantly degrading and destroying the world in which we and all other creatures live. But as I made the fish, each one emerged out of the making as having a different 'life force', some felt as if they had more élan vital than others. Where this came from I wasn't sure, but it had something to do with my relationship with the clay out of which their various forms emerged. Somehow something of my own life force had been transferred into what had been made. Something of my personal spirit had travelled out of my body and had been transported into an inanimate material which now had some sort of animate form. I had in effect performed an ancient shamanic rite and in doing so had also made 'fetishes'. Fetishes that in this case were meant to be found by people who were exploring this small stream in Barnsley.

There are different types of shaman, I don't for instance operate as a spirit walker, the type of shaman that can leave their body behind and travel in spirit form, but as a maker I do feel I have access to a shamanic tool kit. These tools are though not just physical objects but are things possessing spiritual significance that can be used to help make objects come into being, that are designed to connect people with concepts that have the potential to bring about change in their inner thoughts, energies or beliefs.

It was only after working more as a community based artist and eventually as a votive maker, who then found himself more recently working in a hospital setting, that I have perhaps finally begun to see what my previous experiences were hinting at.

Casteneda, C. (1990) The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge London: Penguin

Poggianella, S. “The Object as an Act of Freedom. Kandinsky and Shaman Art, in Evgenia Petrova, (ed), Wassily Kandinsky. Tudo comença num Ponto. Everything starts from a dot , State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Brasilia, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, 11/11/2014 - 28/09/2015, pp. 29-39 Available at: https://www.academia.edu/41629506/The_Object_as_an_Act_of_Freedom_Kandinsky_and_Shaman_Art?email_work_card=abstract-read-more

Eliade, M. (2020) Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy New York: Princeton University Press

Marx, K. (1990). Capital. London: Penguin Classics. p. 165.

See also:

Audience as Shamanic community

Drawings of nervous systems

Why I'm making animist images

In praise of verbs

Exhibition: Piscean Promises

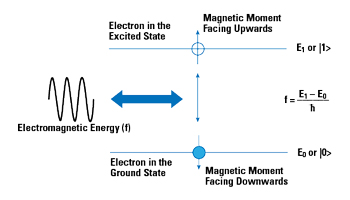

and |1⟩

and |1⟩ , respectively, which in turn can be used to correspond to the spin-up and spin-down states of an electron. Any points on the surface of the sphere correspond to the pure states of the system, whereas the interior points correspond to the mixed states.

, respectively, which in turn can be used to correspond to the spin-up and spin-down states of an electron. Any points on the surface of the sphere correspond to the pure states of the system, whereas the interior points correspond to the mixed states.