Trisha Brown: Performance drawing

Trisha Brown: Walking on the wall 1971

To work horizontally, flat on the floor, or make your work against a vertical, on a wall or an easel, was at one time a vital issue and one that was used to develop a narrative about the objectness of art objects and the performative nature of making marks. A decision to work horizontally as opposed to vertically, was part of a call to eliminate from painting its role as a window on the world. Wall mounted images it was argued at the time, fell into the trap of the picturesque and the horizontal seemed to offer an opportunity to escape this trap. Painting, it was argued, was a physical act, something that belonged to the axis of dance and paradoxically the book, another art form that was usually approached in relation to the horizontal. This argument was one Rosalind Krauss formulated in the text she jointly wrote with Yve Alain Bois, 'Formless, a user's guide'. In this text Jackson Pollock's decision to move from the wall to the floor as a place to work was cited as a seminal act in the ongoing process of moving away from seeing the painting as being about spatial representation, one which was itself prompted by Pollock seeing the Mexican mural artist Siqueiros working on large banners on the floor of a warehouse.

However for myself, it's something that takes me back to being a child. Back then, we never did drawings on vertical surfaces and if we did we were told off. Drawing was done, like reading in books, on flat horizontal tables or on the floor. I still feel safer and more comfortable working on the horizontal, even though today I work between both, sometimes pooling ink on the floor and at others working across a wall surface, so that I can stand back and see what I'm doing. You can move around a drawing on the floor and the idea of top and bottom can change as you revolve around the drawing, its making therefore supportive of changing spaces, rather than you having to respond to a set vertically orientated direction. Most of my best work has emerged from working on the floor, there are so many more angles to discover, each new angle opening out a fresh possibility in terms of spatial representation.

Pollock's decision to work on the floor made his physical relationship with the act of painting much more important, it was easier to see the artist as some sort of performer. Indeed as Harold Rosenberg stated back in 1952, “Since the painter has become an actor, the spectator has to think in a vocabulary of action: its inception, duration, direction—psychic state, concentration and relaxation of the will, passivity, alert waiting. He must become a connoisseur of the gradations between the automatic, the spontaneous, the evoked.”

My cousin as well as my mother and father were all very serious ballroom dancers. Victor Silvester's 'Modern Ballroom Dancing' was a key text for this and the diagrams were fascinating, even for someone like myself that had two left feet.

Victor Silvester: Diagrams from 'Modern Ballroom Dancing'

When learning ballroom dancing small drawings were often made to explain particular moves, they were similar to the drawing below by Barry Gasson, which was used to get his students to understand a heel turn.

Barry Gasson: Sketched biro diagram of a heel turn

These 'how to assemble' technical drawings were what I was mainly doing before I left the steelworks, and my making of them coincided with the introduction of the Maynard operation sequence technique, so it was a good time to go, because what had been a useful skill in that it helped new workers understand how to do something, was now being used by management to develop a set of procedures that got each job done in the fastest possible time. The introduction of this began an erasure of long developed skills in 'feeling' for a machine. My drawings were initially done in consultation with old hands, who could tell you the best way to do something, but they also recognised when it wasn't possible to do something in a certain predictable way. For instance a certain bolt might be more worn than others and therefore it needed to be taken out first. A holistic approach was needed and one that recognised the knowledge in the body, one that allowed someone to just feel for a few protruding bolts and 'know' which ones to deal with first. Men (and in those days it was just men) and machines grew to know each other and over time I began to recognise the 'dance' that we were developing. One that began on the ground and moved up ladders and onto gantries, as overhead cranes came to a stop and we had to quickly get them running again.

|

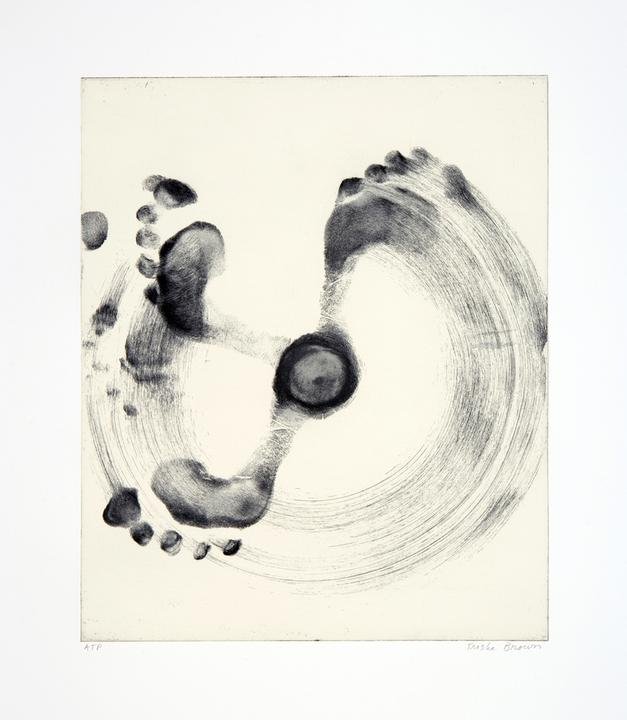

| Trisha Brown: Drawing: foot rotation |

Laban with an example of his notation system developed in the 1920s

Labanotation in use

How to graphically represent change in effort

As you can see from the photograph of Laban and his system above, the method of transcribing movement was paradoxically linked to the vertical, hence the introduction of a more horizontally orientated system, in the 1940s, Benesh notation.

Benesh notation of a gymnastic routine

All of these things are for me a sign of the growing importance of the body when thinking about how to approach drawing. Not just drawing but the way we think we think is being questioned here. I'm going off on one of those side tracks again but bare with me. Over the last few years we have become more and more aware of how complex our body systems are and how deeply interconnected the psychological is with the physiological. For instance there is communication between the bacteria in your gut and your brain, and this communication is linked to both psychiatric health and intestinal disease. Our host bacteria can influence how the brain is shaped for learning and memory. It has also being theorised that when new material enters the gut, our bacteria is sensitive enough to be able to communicate with it. In some way it can 'know' things about the previous life of the new food that has entered the system. This is a deeply profound idea. The thought that your gut will in some way 'know' whether your food's previous existence was a good one or a traumatic one, leads us to rethink the implications of that old aphorism, 'You are what you eat'.

Add to this the way our language is itself linked to the body, "I hope you are able to digest this information'; 'can you grasp what I'm saying?' and the idea of embodied knowledge becomes not just a vague thought, but a real touchable and useable thing. Our assumed superiority over other animals and our celebration of our own brain power, can be put into a different context. Our over reliance on brainpower has prevented us from using or even being aware of many of our other faculties. We hardly use our noses to navigate the world any more, but thousands of years ago we would have needed our olfactory senses all the time in order to select and check out what we were eating and whether or not food was in the vicinity. Above all, we are hardly in touch with our bodies, we have forgotten to 'listen' to them, we don't know how to smell illness or feel for a cure. As we forget our own bodies, so we forget the impact of other things. We forget to speak to the wind as it passes around us, we forget to address the plants that feed us, to sing with the birds as they wake us or to commune with the rocks on which we walk.

In order to attune ourselves to our bodies we need to be 'grounded' and this may mean that we need to develop more of an awareness of the horizontal. By working against vertical surfaces we begin to separate out the frozen mark field, from the act of movement. We separate the result from the doing. You stand back and judge what you have done, rather than immerse yourself in the doing.

In order to attune ourselves to our bodies we need to be 'grounded' and this may mean that we need to develop more of an awareness of the horizontal. By working against vertical surfaces we begin to separate out the frozen mark field, from the act of movement. We separate the result from the doing. You stand back and judge what you have done, rather than immerse yourself in the doing.

It all begins here

When you made your first drawings I suspect you were simply lost in the making and now you are 'grown up' you are supposed to put away childish things and analyse what it is you have done, but as Picasso said, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist on growing up.”

By withdrawing from the world we have developed a powerful set of tools that can dissect this world and extract from it the things that we want from it. However, would we do this to our children, would we dissect them in order to extract from them what we think we need?

Some of my more recent posts have been about certain approaches to philosophy and politics and I have been muttering about whether or not politics can be made to work with certain philosophical viewpoints. I think as I keep returning to similar issues that I am gradually getting to what is perhaps the crux of the issue. Why do art? What use is it to make drawings or any other art form?

If I think back to making those 'how to assemble' technical drawings it was pretty clear what they were being used for, and because they had a clear purpose, they were quickly taken up by the then powers that be, as a way of showing workers how to work faster. So something that began as a way of understanding a process and communicating that process to someone else, became a way of supporting the standardising of procedures as set out by management.

The meaning is the use said Wittgenstein, so perhaps my more recent writings about how my drawings have been used need to be revisited and further unpicked.

Garry Barker: Drawing and Allegory

My artwork is a reflection on what I think the current feeling tone is in relation to our 'condition'. In the drawing above I was trying to visualise the paradox of our desire for constant success, of always trying to climb the ladder of achievement, but not realising that in reality there is nowhere else to go. No matter how hard we try to climb up, we always stay in the same place. We are in reality always here on an earth that we have forgotten to look at because we are so busy trying to climb away from it. How images like this are used, I'm not sure? It is an open ended question, hopefully it helps some people think about the situation we are all in, but it is unlikely that I will be given any clear feedback as was the case when I worked making 'how to assemble' drawings.

This cocky human came from a series of drawings whereby I was wondering whether or not anthropomorphic images might help us become more sympathetic to other non-human points of view. But whether or not these images are in fact useful I don't know and have to rely on instinct or some sort of inner trust to have the confidence to keep making them, each time I make a drawing I am like most artists, looking for that image that might actually communicate something useful to another human being. The fact that most of my images are made horizontally suggests that I also need to consider the performative aspect of this in more detail, but the most important thing is that I can still after all these years get lost in the making.

See also: Drawing and dance Performance drawing Eye Music |

No comments:

Post a Comment